Shortly after setting up camp in the farthest, seemingly most-private Watch Hill Campground site bordering the largest barrier beach nature preserve in the Northeast, typical Fire Island visitors arrived back to back.

First came the deer, who left on their own, followed by mosquitoes that were chased off with bug spray. Then a Fire Island National Seashore (FINS) ranger sauntered by with a friendly reminder not to burn down the park by lighting any forbidden ground fires. Stray joggers, families out for strolls and wandering party people also randomly stopped by to chat at the boardwalk’s dead end that doubled as an entrance to this reporter’s campground—a trip preceding the 50th anniversary of the national seashore’s founding.

“You get special moments out here,” Jiggers Turner, a volunteer camp host who helps keep the peace at the campground every other weekend, said while recalling countless friends made while breaking bread over seaside BBQs. “It’s just a magical place.”

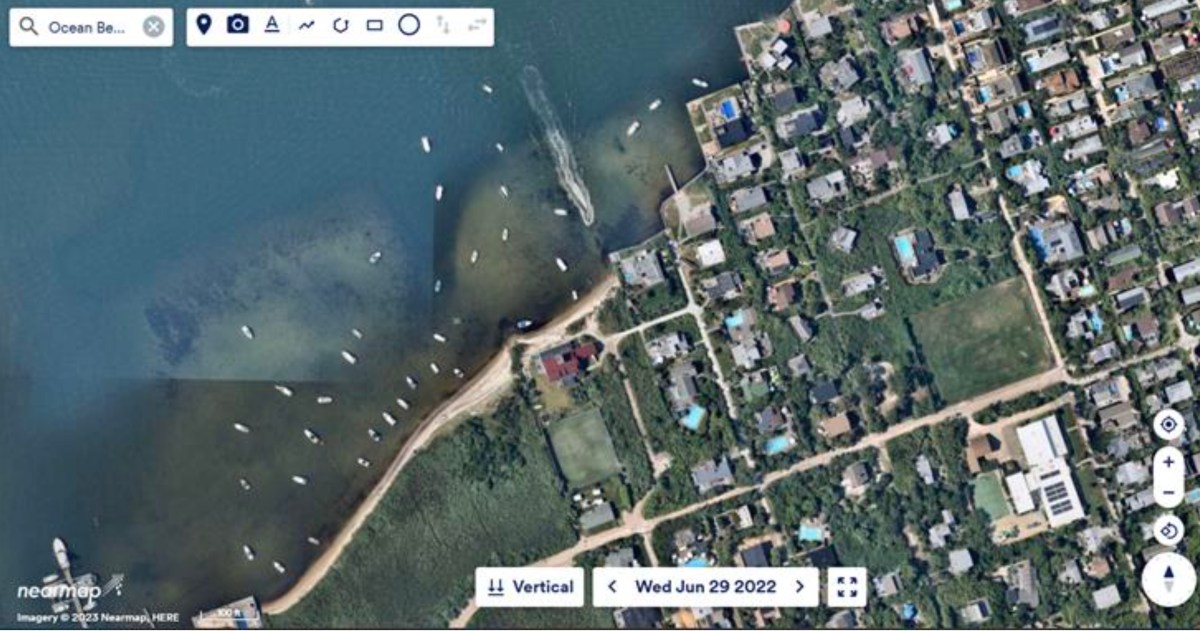

That’s because the campground abuts the Otis Pike Fire Island High Dune Wilderness Area, a seven-mile federal preserve on the east end of the 32-mile barrier island south of Long Island. The pristine beach draws nature-loving backpackers who camp freely in the wild east of Watch Hill. The area is considered “the other Fire Island”—as opposed to the island’s 17 communities to the west, which includes packed bars such as Flynn’s.

Fifty years ago Sept. 3, President Lyndon Johnson signed The Wilderness Act into law, which led to the founding of the national seashore a week later. Fire Islanders had lobbied for the legislation to save the island from Robert Moses’ proposal to extend Ocean parkway from Jones Beach Island through FI as a route to the Hamptons. FINS, a unit of the National Park Service, is marking the anniversary with a slew of events.

“It’s because the seashore is here that…the communities are still here as opposed to a four-lane highway that was going to go down the middle of this island,” Chris Soller, superintendent of FINS, reminded residents last month during a meeting of the Fire Island Association, an umbrella group of civic associations.

But, not all communities were saved. Watch Hill—which also includes a 183-slip marina, seasonal restaurant and lifeguarded oceanfront beach—was built on what used to be Bayberry Dunes, one of three FI communities that were condemned when the national seashore was established. The other two, known as Whalehouse Point and Long Cove, have since been returned to their natural state.

The preservation ensured that beachgoers destined for Watch Hill—or most anywhere on FI—can only get there by boat, except Robert Moses State Park or Smith Point County Park on either end. Those who don’t have a private boat take the $9 half-hour ferry ride from Bay Shore, Sayville or, to get to Watch Hill, Patchogue.

A ranger-run park interpretation center, camp general store and Tiki bar greet Watch Hill visitors upon stepping off the local ferry—named Quaiapen, after a famous Indian chief.

“It’s not exactly like Cheers, but pretty close,” Pam Boyle, president of Friends of Watch Hill, a nonprofit that helps the park with beautification, said of fast friends made on the remote sliver of beach. “It’s a different destination location…it’s way more laid back.”

That’s opposed to the Village of Ocean Beach, the island’s unofficial capital, 10 miles to the west, where homeowners regularly complain about the nearly dozen downtown bars that host a lively nightlife scene. Watch Hill has just one restaurant, The Pier at Watch Hill, which closes for the season Sept. 13 and reopens Memorial Day weekend, and a snack bar. The closest civilization is Davis Park, the easternmost residential community on FI, a 20-minute walk to the west, where there is also only one restaurant: The Casino.

Boaters, campers, backpackers and day-tripping beachgoers mingle in the sandy paradise. After sundown, a hot topic at The Pier is when to catch the best view of the moon. A boater who often docks at the marina said the nickname regulars gave the campground is “Mosquito City.”

Stories of the Watch Hill mosquitoes tend to scare potential campers from coming. Campers have abandoned their gear and fled the tiny biting insects, multiple visitors recalled. The insects are worse in this section of the island because there are no pesticides sprayed in the neighboring federal wilderness, which is why the Friends of Watch Hill ring the marina with mosquito magnets—devices that create a bayside protective barrier from the bugs.

Turner, the camp host, said some days are worse than others, depending upon weather conditions. But, despite widespread speculation that this summer was going to be really bad for mosquitoes across LI, even Watch Hill caught a break. The abundant amount of repellent—including citronella candles, mosquito nets, bug-repelling bracelets and a thermacell device—this reporter packed wound up being overkill.

“Mosquitoes aren’t too bad this year,” said Soller, the superintendent. “Watch Hill, which is like, the worst, I’m hearing isn’t that bad.”

Ironically, one of the lectures rangers offered was about “Our Friend The Mosquito.” That’s in addition to regularly scheduled canoe tours, wildlife lectures and hikes down the beach to see what’s left of The Bessie, a ship that ran aground on FI in 1922. Because there are only 26 campsites, it becomes much easier to reserve a space in the off-season—same as the super-popular Hither Hills State Park campground in Montauk.

Like the rest of the barrier island, Watch Hill largely turns into a ghost town after Labor Day. The general store, open daily during summer, is only open weekends mid-September through mid-October. But, Turner the camp host said: “Everyone shares out here, if you need matches or coal.”

Former longtime camp host Carmen Mejia, who retired two years ago after three decades, offered this advice—applicable to Watch Hill, all of FI and life in general—after packing up her tent for the last time: “You must always be helpful and happy,” she said, “even after your 4 a.m. wake-up call from the local birds!”

For regularly scheduled free nature events at Watch Hill, Sailor’s Haven, the Fire Island Lighthouse and William Floyd Estate, visit the Fire Island National Seashore online events calendar.