Down The Rabbit Hole

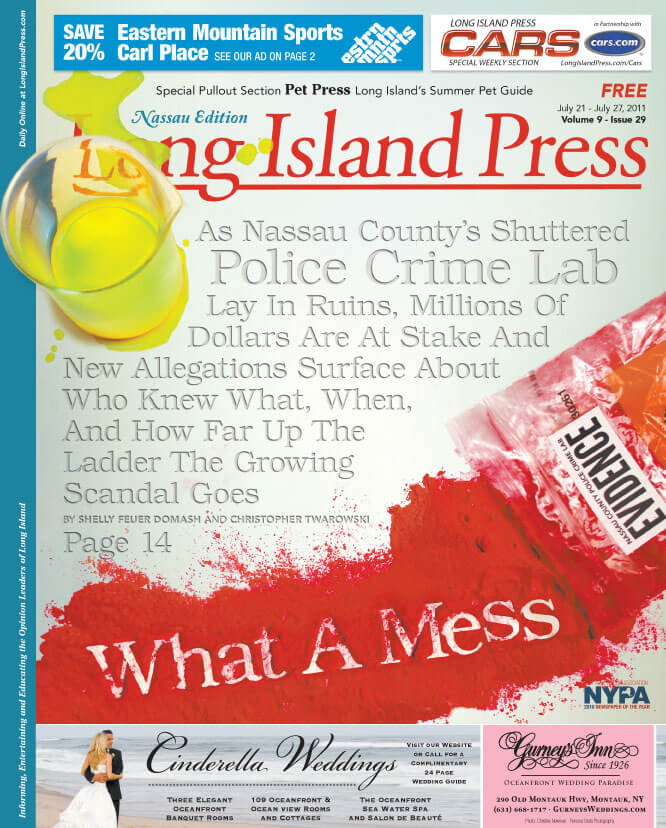

Issues at the Nassau police crime lab were first brought to the public’s attention last December after it became the only such laboratory in the nation to be put on probation that year following a scathing November 2010 inspection report by the ASCLD/LAB highlighting 26 areas of noncompliance—15 described as “essential” by the agency in the review and 10 “important.”

Obtained by the Press, that report paints a hellish portrait of a facility conducting such critically sensitive and important work—after all, the outcome of its tests and analysis, from narcotics to fingerprints to blood work and ballistics, will decide the fates of accused suspects.

Evidence sat unmarked for identification and lacked the proper seals designed to protect its integrity, charges the report. Evidence was mishandled, improperly stored and safeguarded. Internal audits to ensure the lab’s compliance with accreditation standards were never conducted, it reads. Control and standard samples mandated for use and documentation to ensure the validity of examination results were not utilized. Equipment and instrumentation were not calibrated and documentation lacked the necessary oversight used to identify exactly who conducted the tests, continues the report, among a long laundry list of other damning problems.

Echoing Lo Piccolo’s concerns, William J. Kephart, the NCCCBA’s immediate past president, describes the still-unfolding saga of the lab as “beyond troubling.”

“It negates the integrity of the system,” he explains. “You’re talking about the collectors of evidence, the police, the testers of evidence and the ones who conduct everything from the other side of things, the one side that they have complete autonomy to be able to collect, maintain, test and present the evidence—it’s now being revealed to us that they’ve done it either incompetently, or with reckless disregard, or potentially in a criminal fashion. Any of those are problematic, certainly the more extreme being the criminal conduct.”

The lab was shuttered in February by Nassau County Executive Ed Mangano at the behest of Nassau District Attorney Kathleen Rice in the wake of what was quickly becoming a widening scandal and her concerns that some NCPD supervisors knew of inaccuracies regarding drug testing prior to the publication of the ASCLD’s latest report. Just how far back the problems at the lab go—and what police officials, lab personnel, prosecutors and county officials knew; and when they knew it—will eventually be sorted out by Biben, who will release her findings in a detailed report expected soon.

Already, the ramifications have been unprecedented. After the lab’s closure, Rice ordered sample evidence in about 3,000 felony drug cases dating back to 2007 to be retested by Willow Grove, Penn.-based The National Medical Services (NMS) lab. Rice’s spokesman John Byrne tells the Press that because each felony case involves multiple samples, the total number required to be retested could “go into the hundreds of thousands.”

A spokeswoman for Mangano put the tab for the retests as high as $500,000, to be paid for by asset forfeiture funds—monies which would otherwise supplement the NCPD’s budget and be spent on such things as, say, hazmat suits, bulletproof vests, the county’s much-touted Gun Buyback Program or even marine patrol boats.

As David Shapiro, an assistant professor of economics at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, explained to the Press last month, just because the crime lab’s screw-ups are being footed by forfeiture funds doesn’t mean Nassau taxpayers aren’t still ultimately paying for it.

“It is not simply found money that they can say doesn’t come out of taxpayer funds,” he said. “It should be used to defray other unexpected expenditures, instead of being used to pay for something they should have done right the first time.”

“That’s robbing Peter to pay Paul,” blasts Lo Piccolo. “It doesn’t come from a tree. It doesn’t come out of the air. It comes from the taxpayers.”

NMS is also handling all new drug testing, estimated at $100,000 per month—an expense not able to be covered by forfeiture funds.

Additionally, Rice is having independent lab experts conduct a technical review of all blood-alcohol content cases through January 2006, about 1,000 in all. In March, her office sent letters to nearly 300 local and state corrections inmates sentenced for drug and drunk-driving crimes informing them of “lab deficiencies” that may have affected the tests of some controlled substances and alerted them of “administrative errors” in the documentation of blood-alcohol tests. It included contact numbers for the Nassau County Bar Association and Nassau County Legal Aid Society.

Kephart tells the Press he personally has more than a dozen cases directly affected by the revelations—some of which have been greatly impacted, such as three in which clients walked away with “disorderly conducts” instead of felony drug possessions.

As of last month, 69 defense motions had been filed seeking the release of defendants on bail or their convictions set aside based off the problems at the lab, according to Rice’s spokesman Byrne. Her office refused to comment on the Inspector General’s probe or her beliefs regarding how high up the Nassau police ranks knowledge of the problems rose.

The documents cited in Conroy’s motion set the clock for known problems back to 2003, opening the door for countless more challenges—with a potential bill for Nassau taxpayers equally immeasurable. A recent US Supreme Court ruling decided last month, says Lo Piccolo, Bullcoming v. New Mexico—which will require the District Attorney’s Office to bring forth all the witnesses who handle and test evidence when offering such evidence at a hearing or trial—will compound those costs. Some, such as Kephart, believe the problems go back even further and that everyone at the top—from District Attorney Rice to former Nassau Police Commissioner Mulvey (who retired in April)—were in the know.

“People asked me in the beginning, ‘How far back does this go?’” says Kephart. “I always answered, ‘Infinitely.’ And I still say—based on what we know now, it’s 2003—I believe it goes back into the ’90s.

“It was systemic,” he continues. “It wasn’t a one-time or two-time or under-one-administration or -one-commissioner or -one-lab-director-type of issue that you can confine to a certain group… I find it very troubling that our officials here in Nassau County, from the county executive’s office …to the police department to the DA’s office—no one knew this? And yet Albany and people upstate know of these issues?

“Clearly there was dialogue in memos and letters between the state and Nassau County’s officials,” he adds. “There was phone conversations and possibly in-person conversations that further delved into this area. To tell us that, ‘We didn’t know,’ I find completely unacceptable and quite frankly, unbelievable. I don’t think anybody finds that credible.”

“I can’t imagine they didn’t,” adds Lo Piccolo. “To imagine they didn’t is almost making a mockery of people that are making hundreds of thousands of dollars who are required to protect and serve the highest-taxed county in the nation. It’d be shocking if they didn’t know.”

Kephart has asked for the District Attorney to retest evidence from felony cases dating to at least 2003. If the evidence no longer exists, “You dismiss the charges,” he argues.

Lo Piccolo agrees, charging there should be an additional probe into lab personnel to get at the root of its problems and begin to address the “hundreds or thousands of cases” potentially affected even by just one “bad apple.”

Byrne, the district attorney spokesman, tells the Press whether such retests would be conducted “depends on the results of the testing we are doing now. If an individual requests one and filed a motion, we will retest.” Rice has stated publicly she did not know about problems at the lab until the December 2010 report.

In March, Brian Griffin, of Garden City-based firm Foley Griffin, LLP, convinced Judge George Peck to throw out 30-year-old Erin Marino’s aggravated vehicular assault and DWI conviction based on problems at the lab. That ruling could also lead to thousands of similar contests. Prosecutors are appealing the decision.

Marino’s court proceedings offer the first glimpse behind the curtain regarding who might have known what, when, and just how far up Nassau’s chain of command that knowledge rose.

Testifying at a February hearing was the lab’s former director, Det. Lt. James Granelle—who was reassigned by Mulvey in December—and his interim replacement, Dr. Pasquale Buffalino. Griffin found both testimonies eyebrow-raising.

“Granelle confirmed what we believed we knew, which was that the problems at the lab were longstanding and they were pervasive throughout the lab,” he tells the Press. “And that they were known for years by members of the police department. So this was not something that just happened overnight. And it wasn’t something that was known to a singular individual at the lab. It was well-known, widespread and longstanding. That was a big thing from him. What we also learned is that Lieutenant Granelle had really no background—he didn’t have a master’s degree or a PhD, and he had no background in running a lab. So, generally speaking, in a forensic lab, you’d expect it to be run by someone with a PhD who’s got a wealth of experience in running a lab. Not the opposite.

“It’s shameful,” he continues. “Granelle told us he certainly pushed it up to his supervisors. It was not something that he kept secret or he hid or covered up. In fact, he said it was known to his immediate supervisor—which is a very high-ranking person in the police department. So, the head of the lab knew, and the person above the head of the lab. These are not low-level line people at the lab. These are the leaders of the police department.”

Contacted by the Press, Granelle declined to discuss his knowledge of what took place within the lab: “We are in the middle of an investigation that is ongoing and I don’t feel it is proper to comment.”

As Conroy’s motion documents, former Nassau Police Commissioner James Lawrence knew about the lab’s subpar conditions in 2003 and 2006. He and several other police and civilian lab personnel allege former Commissioner Mulvey and other county officials did, too.