It was 70 degrees in Central Park and Islip on Nov. 28, a temperature that shattered a 115-year-old record for New York City and trumping Long Island’s previous of 68 degrees for that date in 1995. The mercury hit 72 degrees in Newark the same day—tying a 1973 benchmark.

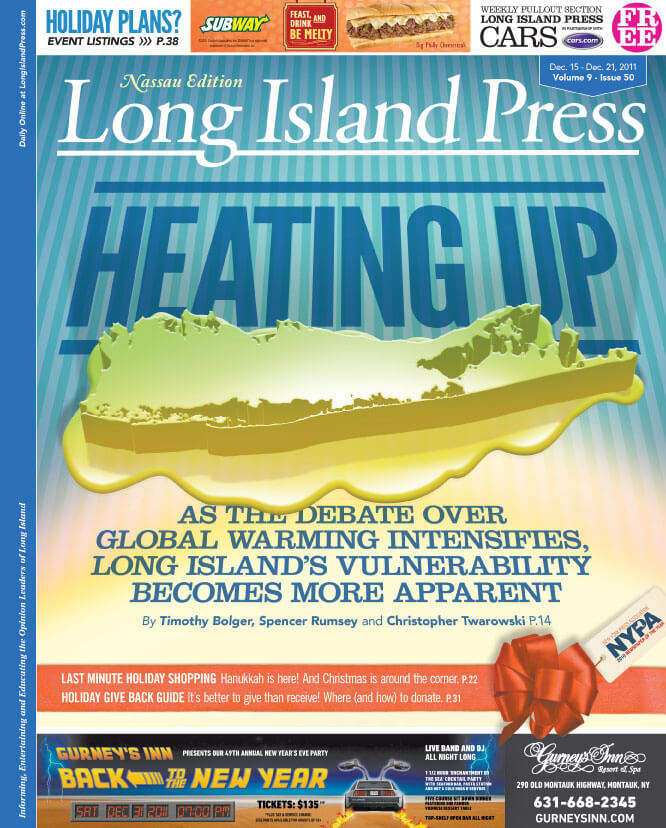

Record-shattering temperatures, above-normal precipitation and extreme weather, however, are just several meteorologically consequential indicators a growing number of environmentalists, scientists and weather experts, among others, locally and from around the world, point to as part of a mounting body of evidence suggesting the Earth’s atmosphere is heating up—and heating up due to the direct actions of man via greenhouse gas emissions.

The unprecedented local highs and unusually mild December to date cap off a year of extreme weather across the country ripe for the record books, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)—a record 12 climate and weather disasters each caused $1 billion or more in damage along with their tremendous loss of human life. Globally, nations across the planet experienced extreme weather events and natural disasters in 2011.

While it is debatable whether all the aforementioned tumultuous weather swings and tragedies can be directly linked to man-made global warming rather than a natural climate shift and events, more and more scientific research from across the globe points to a hotter future, fueled by the heat-trapping capabilities of greenhouse gases—emissions that spark a cannibalistic cycle that feeds upon itself; warmer air, warmer oceans, more of the planet’s ice melting, a rise in sea levels, increased precipitation, extreme temperatures and all the associated issues.

This past weekend delegates from 194 parties wrapped up the United Nation Climate Change Conference in Durban, South Africa, to come up with a solution—specifically by hammering out the terms for controlling carbon emissions by 2012, when the first commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol, a binding self-imposed commitment among nearly 200 nations (not including the United States) to reduce greenhouse gases, expires. The conference reached an accord leading to an eventual agreement to be prepared by 2015 and to be fully implemented by 2020—an approach that has received criticism among some environmentalists for being too little, too late.

Long Island, simply from being just that, an island, has an increased vulnerability to the potentially disastrous effects of global warming, say experts and scientific studies. Suffolk County is the largest agricultural producer in terms of income in New York State. Our nearly 3 million residents extract their drinking water from underground aquifers. Nearly 300,000 people live on the barrier beach communities on our South Shores, and about 7,000 homes are currently within a 10-year flood plain right now. All these factors add extra significance to our plight.

“We’re at ground zero,” stresses Adrienne Esposito, executive director of Farmingdale-based Citizens Campaign for the Environment—one of many local environmentalists who have been trying to sound the alarm before it’s too late.

“It can be catastrophic,” says lifelong environmentalist Morris Kramer, of Atlantic Beach, about the disastrous wrath of rising sea levels and more intense storms on local oceanfront communities. “Just the damage to the Long Beach barrier island would be catastrophic.”

“Nature is being displaced,” warns Long Island environmentalist Lisa Schary.