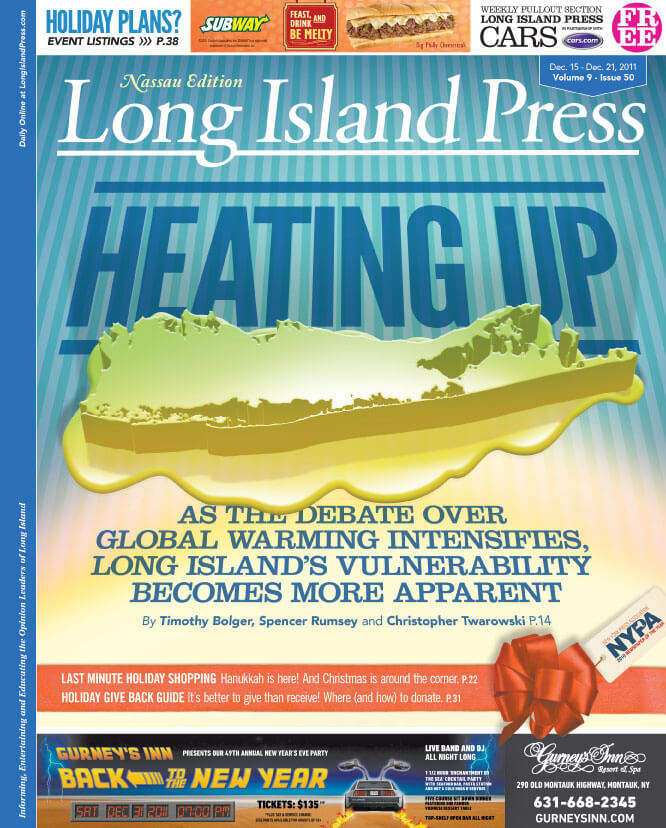

The future is bleak:

“Temperatures are increasing, precipitation patterns are changing, and sea level is rising,” states its opening line about risks to New York. “These climatic changes are projected to occur at much faster than natural rates because of increased amounts of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.”

Heat waves will intensify and become more frequent, increasing heat-related illness and death, it foretells. For Long Island: “Coastal flooding due to sea level rise and storm surge will increasingly put lives and property at risk. Health, water quality, energy, infrastructure and coastal ecosystems are all affected.

“In 2020, nearly 96,000 people in the Long Beach area alone may be at risk from sea level rise under the rapid ice melt scenario; by 2080, that number may rise to more than 114,500 people,” it declares. “The value of property at risk in the Long Beach area under this scenario ranges from about $6.4 billion in 2020 to about $7.2 billion in 2080.”

Atlantic Beach’s Kramer warns that LI’s barrier beach communities don’t have to wait till 2080 to feel the disastrous effects of global warming, or even 2020—Long Island is susceptible now.

“It really is that 96,000 people are threatened now, because the bay has filled with sand in many places, so basically, if you put the same amount of water in the bay, it’s going to expand, getting all the communities slightly north of the bay and Long Beach also, because Long Beach will flood from the bay. They’re vulnerable already,” he says.

Global warming has some of the more severe ramifications for New York City and Long Island, which contain the “highest population density in the state,” the report states: “Sea level and storm surge increase coastal flooding, erosion and wetland loss,” it reads. “Challenges for water supply and wastewater treatment; Heat-related deaths increase; Illnesses related to air quality increase; higher summer energy demand stresses the energy system.”

Temperatures could rise between 3 to 5 degrees by the 2050s, predicts the report, and between 4 to 7.5 degrees by the 2080s. Precipitation could increase by 10 percent in that timeframe, it reads.

Global warming’s climate-altering effects are also becoming obvious to Long Island’s farming community.

“Most of my farmers do believe that the weather patterns have changed,” Joseph Gergala, executive director of the Long Island Farm Bureau, tells the Press. “In my life time, I used to grow potatoes with my father, and we’re certainly seeing more precipitation. What we used to call a ‘hundred-year storm’ seems like they’re happening more frequently.”

Jay Tanski, senior coastal processes and facilities specialist of New York Sea Grant, a joint project of Cornell University and the State University of New York at Stony Brook, who specializes in studying erosion, agrees that there’s reason for Long Islanders to be concerned.

“Long Island is vulnerable to erosion and flooding because it’s the largest island in the contiguous United States. It’s vulnerable right now,” he tells the Press. “We don’t have to wait for climate change, or an increased rate of global warming to cause issues for us.”

Tanski says storm damage, particularly from nor’easters, is already serious, and he gives that threat a greater immediate priority than sea level rise over the next few decades. If houses now being built in low-lying areas near the Great South Bay and the Peconic Bay were raised an additional foot, he says, “you’ve taken care of another 30-to-40-years of sea rise.”

But policymakers have to focus now.

“I would say that you have some time, but you better start getting very good information because you’re going to have to make decisions that will have long-term consequences and long-term costs,” Tanski says. “Nothing is going to get better, but we don’t know how much worse it’s going to get…. There is a consensus that, okay, we are changing the environment, and things are warming, but what that’s going to do, especially in the coastal realm, is more ambiguous than…most people like to think.”

Yet despite the mounting physical evidence of global warming and calls for immediacy, as one Long Islander learned firsthand in Durban, coming up with a solution that everyone can agree to—even among the international representatives meeting specifically for that purpose—is no easy process.