WAVES OF MUTILATION

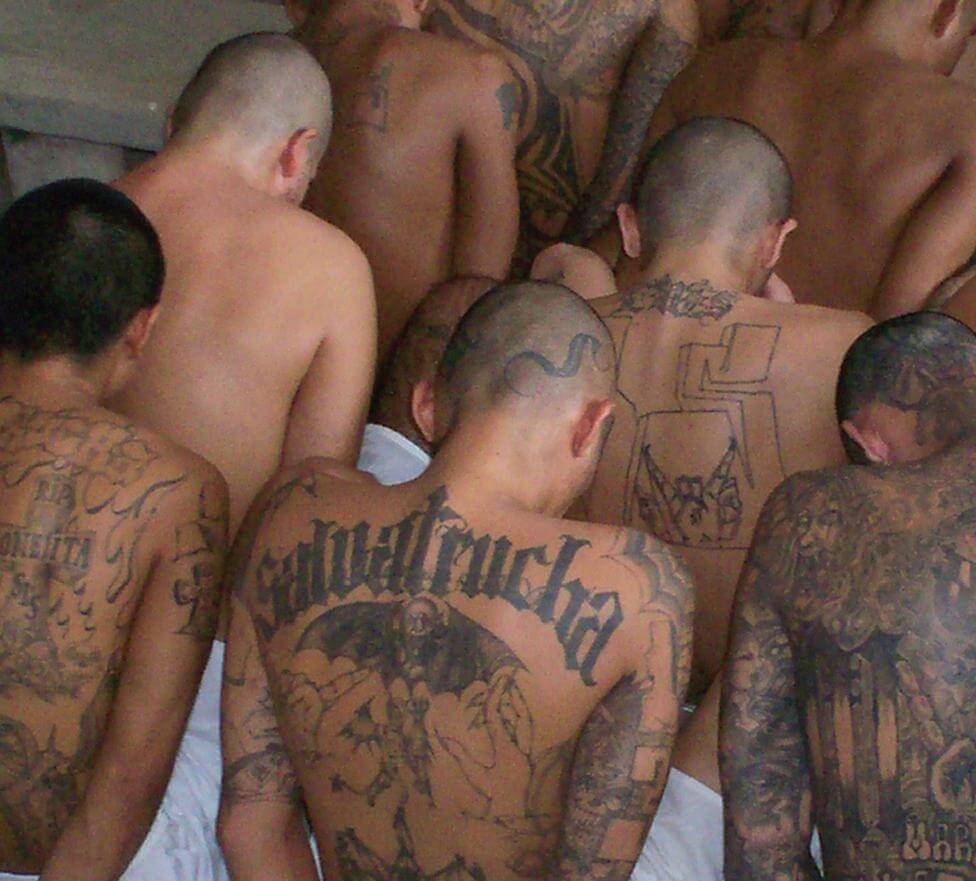

It’s been four years since an all-out gang war seized central Long Island, forcing Suffolk police to rethink their approach as a spotlight fell on murders in poor communities.

Anti-gang policing became politicized when a deadly crime wave hit Brentwood and Central Islip, claiming more than a dozen lives in less than a year from mid-2009 to early 2010—most of which ending in LIGTF-led arrests of MS-13 members. Public outcry at the time prompted police to flood the area, dozens of neighborhood watches to form and then- County Executive Steve Levy to take drastic action.

The ex-county exec created a police unit targeting gangs made up of investigators that were originally members of separate gang units in each of the seven Suffolk police precincts. (Announced a week after a July 2009 Press story detailing Nassau’s county-wide gang unit, and Suffolk’s lack thereof.) Shortly later, Suffolk police also joined the LIGTF, eight years after it formed in 2002.

“We loosened the grip of organized crime through federal racketeering statutes,” Levy said while touting the moves in his 2010 county address. “We should do the same when it comes to combating gangs.”

When informed of the recent withdrawal from the task force by the Press, Levy says he isn’t surprised, given what he characterizes as his successor Steve Bellone’s position that “they don’t want to work with the federal government,” adding that perhaps the move has to do with pressure from immigration lobbyists, or is the result of the “expensive” police contract passed Oct. 9 and the need to redeploy cops to highway patrol.

According to many experts, being part of a federal task force has major benefits, not the least of which is the applicability of the RICO Act, which means longer federal prison sentences and gang members looking to cooperate in order to lessen their terms.

“Federal lawsuits are an awesome weapon,” says Eugene O’Donnell, professor of law and police studies at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. “They are a gang’s worst nightmare. They are effective and fearsome.”

“They start spilling their guts,” one source says about its effect on perpetrators.

Another advantage is these task forces can accumulate intelligence from numerous sources and locations throughout the country. As a federal agency, they can also easily investigate cases that extend abroad. They have a centralized database and can deport documented gang members. Using the knowledge supplied by local jurisdictions, federal task forces can take that data one step further and are able to combine local state and federal power, resulting in more arrests and successful prosecutions.

Then there’s the federal funding, which sources interviewed for this story believe kneecaps the SCPD’s official excuse for the detectives’ departure. In actuality, they say, it’s their move that will end up costing the police department—aka already strapped Suffolk taxpayers—plenty.

That’s because when a local law enforcement entity aids or assists or works in cooperation with an arm of the Department of Justice, it can keep a portion of the proceeds of a crime through the department’s asset forfeiture program. The exact amount depend on a number of variables, such as the case, the level of cooperation and the amount money seized, but it can mean millions or even tens of millions of dollars.

“By yanking these guys here they forfeit any claim to that money,” says one source.

Additionally, local police departments also apply for various grants to buy equipment, pay for overtime, to help with training, etc., he says—another revenue stream that would potentially be jeopardized by the recent exodus.

“Typically, a representative from the U.S. Attorney’s Office has to certify that the department is cooperating with federal efforts and is a good enforcement partner,” he adds.

Things were relatively quiet in Suffolk for a while after SCPD joined LIGTF. But last year, after Levy announced he would not seek re-election to settle a criminal probe of his fundraising, the gang unit became fodder in the hasty campaign to replace him.

Democrat Bellone, who succeeded the Republican this year, made breaking up the gang unit and sending the 39 investigators back to the precincts a campaign promise last fall—one he fulfilled less than a month after taking office in January.

“The gang officers are back in the precincts where they belong so that they can fight these gangs on the streets, in these communities, where the problems are occurring,” Bellone said at one of his first press conferences on the new job.

“Gangs are a major problem in Suffolk County and it’s one of the department and the new administration’s focal points,” added then-Acting Suffolk Police Commissioner Edward Webber. “We are determined to fight. We can’t let them take over the streets. We’re going to work together in partnership…[with] other law enforcement agencies. We are in this together.”

Yet behind closed doors, it’s around this same time, sources say, that Suffolk police brass discussed pulling out of the LIGTF, roughly three years after joining.

Law enforcement sources who saw the results firsthand scoff at the SCPD’s official spin that it now has to do with the budget.

“I hardly think that basically three detectives are going to make the difference to the precinct detective squads compared to the amount of work that they did in the gang task force,” a source with knowledge of the reassignments who asked not to be named. “But it’s an easy thing for them to say because it’s true: The precinct squads are short.”

It’s a sentiment shared by many interviewed for this story—along with the need to put them back on the task force, immediately.

“The police department has made a wrong decision and they need to put their staff back on the FBI task force,” says Lenny Tucker, president of the Brentwood Association of Concerned Citizens, an advocacy group. “The indictments that are being handed down show you the work that was done. I can understand if there was no progression, but they’re catching the people who are committing these crimes.”