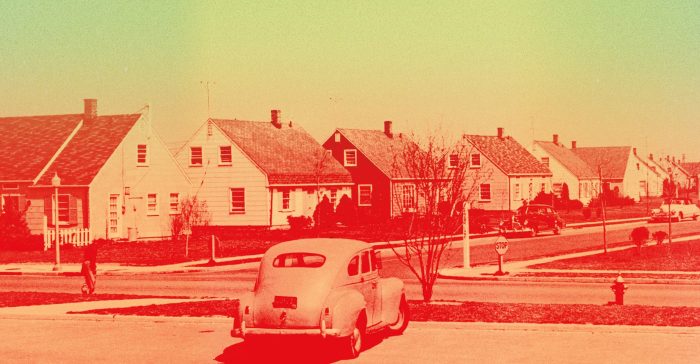

There’s a stretch of Cantiague Rock Road in Hicksville, just north of Hicksville High School, its middle school and Lee Avenue Elementary, where pedestrians aren’t permitted to stand on the sidewalk.

There are no signs stating this, no barricades cordoning the area off, no flashing lights demarcating a construction zone or telling passersby it’s private property. But if you stop there for even a few moments to take a gander at the fenced-off property—three decrepit-looking buildings and their equally decrepit-looking parking lots—any day of the week, during any time of day, 24/7, someone will unquestionably instruct you to keep moving, to shuffle along, scram.

If your intention is to snap a few photos, as mine was at about 3 p.m. on the Sunday before Christmas Eve, you’ll get more than advice; undoubtedly you’ll receive an angry visit by one of several charged-up, plain-clothed men shouting for you to buzz off—they might even chase you away.

There’s really not much to look at, though. Sandwiched between a distribution warehouse on its south, a driving range and children’s playgrounds of Nassau County’s Cantiague Park on the east, and the county’s Department of Public Works headquarters on the north, the three parcels at 140, 100 and 70 Cantiague Rock Road are silent and devoid of life.

The latter’s facade is a beat-up, worn-down brown, with cloudy windows, drawn blinds and the faded outline of its former tenant, Air Techniques, tattooed on its side. At 100 next door stands a naked flagpole, a vast loading dock area long since abandoned and weeds towering several feet high. Several massive metal frames arch above an alley between it and the 140 building, which has part of its exterior wall peeling off and is covered in shredded plastic.

It’s here where an outhouse-shaped guard booth is manned around the clock.

“Off the property,” said an agitated, bespectacled, middle-aged man sporting a moustache when a camera crew and I recently visited to ask a few questions. A mock “Terrorist Hunting Permit” was fastened to his window. “This is private property. Get off the property,” he commanded, refusing to explain who he worked for before slamming the door.

[Click here for more photos of Hicksville’s atomic waste site]

There’s a secret in Hicksville. It’s a secret that only a handful of residents of this suburban hamlet know all too well while way too many others haven’t a clue. A secret that has already cost one of the biggest communications companies in the world millions and may end up costing them much, much more. It’s a secret that no matter how tight a lid the security guards stationed there or the site’s owners, Verizon, try to keep on it, the truth is literally leaking out—bleeding into the soil, contaminating the air and poisoning Long Island’s precious groundwater supply.

It’s a revelation that Ronkonkoma resident Gerard Depascale, a father of three and recent grandfather, and his former coworker Liam Neville, of Bayside, Queens fought relentlessly to find out, a reality they live with every single moment of their lives, one the global communications giant is doing everything in its power to control. It’s an ongoing tragedy that a federal judge recently made even more tragic for the plaintiffs; a reality that will undoubtedly affect more families in the future.

This vacant 10.5-acre stretch of land, just north of those schools, separated by a chain-link fence from the public park and situated directly across the street from Nassau BOCES Career Preparatory High School, is a radioactive toxic waste site where nuclear elements and fuel rods were fabricated and processed during the nation’s early atomic energy program in the 1950s and 1960s.

Uranium was burned here. It was released into the surrounding neighborhood from an open “smelting oven,” according to one former worker—or within a “burning building,” according to another. It was also buried here, along with nickel and much more. Unknown amounts of chlorocarbons—Tetrachloroethene, or Perchloroethylene, known as PCE and PERC, respectively—and byproduct chlorinated hydrocarbon Trichloroethylene, or TCE (classified as a human carcinogen by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency), were dumped into unlined sumps and leeching pools, and currently reside in the soil, the groundwater and have volatilized into the air.

People who unknowingly worked atop the site, such as Depascale and Neville, have contracted rare—make that extraordinarily rare and obscure—cancers.

Neville has a rare kidney cancer called membranous nephropathy. Following years of dialysis, he was lucky enough to find a donor and receive a transplant, though now he’s currently facing some complications.

Depascale has an even rarer cancer, called extra-skeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. It’s Stage Four and it’s in his bone marrow.

Besides the unquantifiable pain and anguish suffered by the two and their loved ones are insurmountable medical bills and an inability to work, not to mention their shortened lifespan.

Depascale and Neville, both former employees of Magazine Distributors, Inc. (MDI), who worked at the 100 building and its warehouse from about 1990 till 2002, when the company suddenly moved (employees were told it was the end of their lease; court transcripts reveal General Telephone and Electronics Corp. (GTE), who merged with Verizon in 2000, “assumed” the lease from MDI after purchasing the 140 property in 1999 for contamination remediation efforts and the 70 location in 2004) are literally battling for survival.

They’re also fighting for justice.

Depascale, his wife Joanne and Neville filed a toxic tort lawsuit against Verizon and its predecessors claiming negligence and liability, among other charges, in Nassau County State Supreme Court in 2007. The case was moved to federal court at the request of the defendants, who argued defense under government contractor immunity law—which protects contractors who perform federal work from lawsuits such as theirs. The jury heard expert testimony from both sides, also learning that an untold number of records relating to the Hicksville site had simply disappeared from GTE/Verizon’s files. Near the end of the trial, the presiding judge in that case, U.S. District Judge Leonard D. Wexler, impaneled an additional two alternate jurors, and according to Neville, ordered that for them to win, the verdict would have to be unanimous.

It was, and on Nov. 12, 2009 after just eight days of testimony, the jury issued its verdict, awarding the trio $12 million on the grounds of causation, negligence and damages, finding they got past the federal contractor immunity.

That detail of this saga has been reported before—as well as the settlement of a 2002 complaint alleging that nearly 300 Hicksville residents who live near the site developed cancers and related injuries because of it.

Unreported is that more than five months after Depascale and Neville’s win, following an appeal by Verizon, Wexler, in the rare instance of a judge going against the will of a jury—ordered the case be retried, on limited grounds, effectively nullifying the award and ultimately, deeming the jury’s verdict a “miscarriage of justice.”

They lost that trial—Neville bleeding through his shirt in the courtroom, though restricted to tell the jury that he or Depascale were even ill. They appealed, Verizon filed a cross-appeal, and now the pair is set to present oral arguments for why Wexler’s order for retrial should be overridden and the jury’s award reinstated before the Second Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals Jan. 15. Yet it’s not simply reparations for their medical debts that they’re fighting for now.

The fate of countless other former residents, former MDI employees and others who’ve worked at the site may literally hang in the balance, since Wexler ordered a stay on another pending class action “medical monitoring” suit that could include innumerable plaintiffs until Depascale and Neville’s appeal has been decided.

A Press investigation—part of an ongoing series into how its industrial and military past is affecting the Island’s current-day environment and residents and consisting of the analysis of hundreds of pages of state and federal records, including investigative reports concerning contamination to the soil, air and water at the site, remediation plans, maps, assessments, internal correspondence and thousands of pages of court filings and transcripts, among others—has discovered that GTE, Verizon and state regulators certainly knew or should have known about the site’s contamination years before Neville and Depascale and the hundreds of others who worked along Cantiague Rock Road ever stepped foot there.

It reveals a twisted and unconscionable game of pass-the-buck when it comes to informing these workers of even the potential for adverse health effects, a game that continues to this day. What’s absolutely indisputable is that many people living around that site and who’ve worked there have developed horrific cancers. And that some have already died from these.

Additionally, the records reveal that despite several state-supervised “voluntary” remediation efforts at the site—the largest conducted by GTE, which one report states included the excavation and removal of at least approximately 100,000 tons of contaminated soil and unearthed, partially filled tanks of radioactive and carcinogenic elements and chemicals—it remains contaminated and its true ramifications on the health and safety of not only Hicksville residents, but all Long Islanders (since we all share drinking water aquifers), may never be known.

Neville, a bachelor, self-professed pessimist, horse bettor and the more outspoken of the pair, staked he and Depascale’s odds in court at 60-40 in Verizon’s favor when I first sat down with them six months ago. Recently, those self-ascribed odds have gotten worse. He says 70-30 now, in Verizon’s favor.

“You ever feel like punching someone in the face and there’s no one there to punch, you’re that angry?” says Neville of how he felt when he learned what was beneath his workplace. “This is a 60 Minutes episode. This happens to somebody else. This doesn’t happen to me. This is insane.”

For Depascale, who has a family to provide for, things have been even worse. Adding even more insult to so much injury, his workman’s compensation claim—which he originally won, is back in court again following two appeals.

“Betrayed,” is how he feels. “They should have told us that that place was contaminated. If I knew about it, at least it would have been my choice to be there, not their choice.

“It’s been a nightmare since I got sick,” he says.

Requests for comment to the plaintiffs’ attorney, Joseph D. Gonzalez, and William H. Pratt, a lead attorney for the defendants in the litigation, went unanswered for this story.