Scientists at the Brookhaven National Laboratory call this coming Feb. 11 the “cool-down” day. That’s when they start chilling the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider to the temperature of liquid helium (more than 450 degrees below zero) so they can begin colliding polarized protons in a series of physics experiments set to run through the spring that would have thrilled Albert Einstein, had he lived long enough to see them.

The world-renown scientist will be there in spirit, no doubt, because “all nuclear and particle physicists owe a debt to Einstein,” says Robert Crease, a Stony Brook professor and the lab’s official historian who wrote “Making Physics: The first 25 years of the history of BNL” and is now working on the sequel.

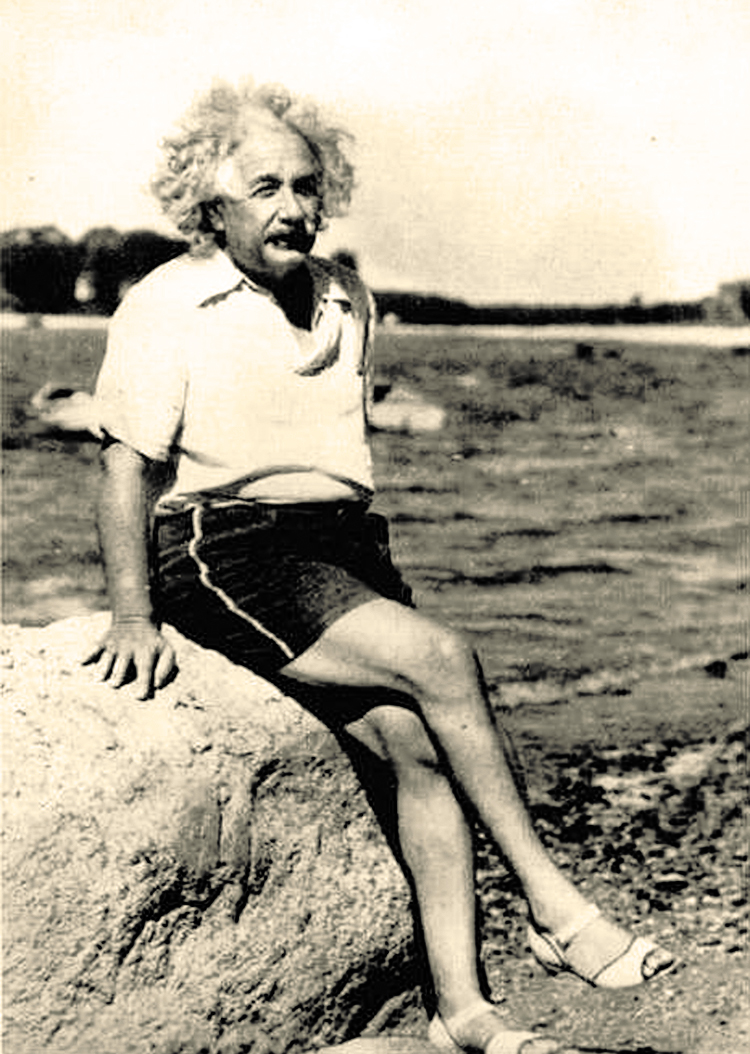

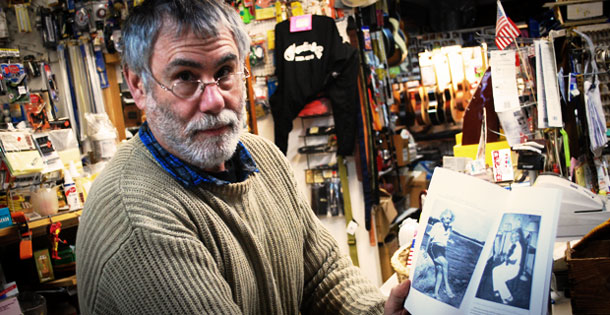

(Photo by Reginald Donahue/Courtesy the Rothmans)

The circular subterranean electro-magnetic corridor collider, known as RHIC (pronounced “Rick”) for short, “relies very essentially on Einstein’s theory of relativity,” says Berndt Mueller, BNL’s associate director for nuclear and particle physics, because it explores a non-linear strong force similar to gravity. “If Einstein were alive today, I think he would be very fascinated by the results.”

For Einstein, who died in 1955, Long Island only meant a place where he could enjoy himself.

In 1937 the Long-Islander mentioned that Einstein had “passed the summer” at Maud Klots’ home on West Shore Road, which runs along Huntington Harbor, and sailed to Halesite to pick up his mail. If he made much of a splash on his vacation, it didn’t last long.

The same can’t be said for the memorable months he spent out east in 1939 when he rented a cottage on Nassau Point in Cutchogue so he could put his sailboat in Horseshoe Cove. Before that summer was over Einstein would sign a letter to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt warning him that the United States couldn’t afford to wait while Nazi Germany was possibly making a nuclear weapon.

But that dire notion was far from his mind when he took his sister Maja, his step-daughter Margot, his son Hans, and his secretary Helen Dukas to the North Fork. They even brought a little Airedale terrier that scratched frantically at a door in the living room whenever Einstein would try to close it, prompting him to ask a visitor once: “Do you suppose he can see the door is contracting in the direction of its motion, and he does not know what to make of it and it makes him angry?”

The answer eluded him but the question showed how he thought, even on holiday. His summer place is still there on West Cove Road (Einstein had misspelled it “Grove” in a letter). The house has changed, and the neighborhood has grown, but he might recognize the lingering sentiment. A local woman named Louise Thompson, whose parents lived across the street from him, recalled in a story that Newsday ran on the centennial of his birth in 1979, that he had “wanted to have access to the beach through our property [and] my mother wasn’t too interested in that.” After all, she said her mother told him, “Professor Einstein, you are here for privacy and so are we.”

Apparently the younger generation on Nassau Point didn’t appreciate the two main activities Einstein did to occupy his time there: sailing and violin playing. Einstein, who never learned to swim, had no pretentions about his nautical prowess. He had named his 17-foot glorified rowboat the Tinef, which is supposedly Yiddish for junk.

Apparently the younger generation on Nassau Point didn’t appreciate the two main activities Einstein did to occupy his time there: sailing and violin playing. Einstein, who never learned to swim, had no pretentions about his nautical prowess. He had named his 17-foot glorified rowboat the Tinef, which is supposedly Yiddish for junk.

“We kids who were growing up here know how to sail. He didn’t,” Thompson said. “He’d tip over, and once I can remember some of the local boys going out to rescue him.”

That wasn’t an uncommon occurrence, apparently, with Einstein at the helm. After a sailing mishap in the Long Island Sound when his family had rented a cottage at Old Lyme, Conn., in 1935, the New York Times ran the headline, “Relative Tide and Sand Bars Trap Einstein.”

Thompson and her Peconic peers weren’t much impressed with Einstein’s musical prowess, either, perhaps because he’d play his instrument “all the time” on his porch during those summer evenings and “we kids didn’t think much of it. We thought he was terrible.”

Fortunately, Einstein had a big fan in Southold. David Rothman, who had opened Rothman’s Department Store in 1919, hadn’t graduated high school but he had maintained an avid interest in science. He recognized Einstein’s stepdaughter Margot when she entered his store looking for a chisel sharpener (she was a sculptor). Rothman presented it to her as a gift and asked her to convey his “respects to her father,” as he recalled.

The next day, Einstein came into the store himself looking for “sundials.” Or so Rothman thought and he dutifully showed him the one he had in the backyard. Einstein pointed to his feet. He really needed sandals, so Rothman sold him the largest pair he had left: women’s size 11. Einstein, who’d described himself in a letter to a friend as “a kind of ancient figure known primarily for his non-use of socks and wheeled out on special occasions as a curiosity,” gladly wore them all summer, along with a pair of shorts tied around his waist with a piece of rope, and a white sports shirt.

When the 60-year-old scientist had first entered his store, Rothman, then 43, was playing Mozart’s “Symphony No. 40” on his phonograph and they started talking about music. Rothman had begun playing the violin when he was 36; Einstein had started when he was six, but he insisted they play together. The next evening Rothman came out to Nassau Point with his instrument and some sheet music, but he was out of his league almost immediately and so they spent the rest of the night chatting. They clicked, and later Rothman arranged many musical evenings at his Southold home where Einstein and a few friends would play. Sometimes almost a hundred people listened outside, hoping for a glimpse of the famous scientist.

Rothman’s recollections of his experiences with his celebrated companion have been published by his daughter Joan Rothman Brill and his grandsons Ron Rothman, a talented guitarist who runs the Southold store today, and Chuck Rothman, a science fiction writer living in Schenectady.

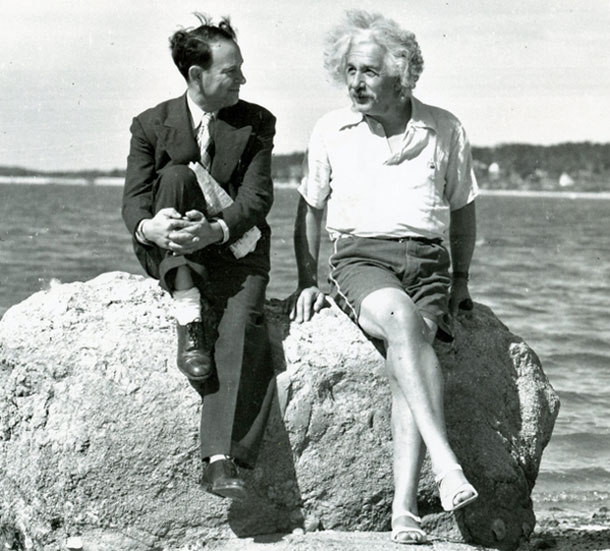

“The way I see it,” says Ron Rothman, “that summer my grandfather palled around with Albert Einstein to the point where he would come in and he would sleep on the couch. He would spend time playing music, and they would go around doing things.” In the photos of his “gramps” and the scientist, Einstein is in vacation mode casual, while Rothman is wearing a business suit because “that’s the way people dressed for work then,” his grandson says with a smile.

One day Rothman waited hours for Einstein, who had planned to sail around Nassau Point to Southold. It was almost dark when the phone rang at his store, as he reminisced to Newsday. On the line was a New York City cop on vacation, who shouted, “Rothman, there’s some wild-looking guy that needs a haircut—some helluva looking looney—down here on the beach wanting to know where you live!”

Another time Einstein had just come back from sailing and Rothman was talking to him on his porch when two harried young Hungarian physicists living in exile, Leo Szilard and Eugene Wigner, drove up. They’d come from Manhattan to see him and couldn’t find the cottage until a kid in town had told them which one it was. Szilard, who had studied with Einstein in Berlin and even shared a patent with him for a “new, noiseless refrigerator,” was on an urgent mission because he’d had the disturbing revelation that uranium could be used to create a nuclear chain reaction.

“I never thought of that!” Einstein exclaimed in German. The two Hungarians first thought they’d get Einstein to write the queen of Belgium, Einstein’s friend, and warn her that if the Germans conquered her country, they’d gain control over the Belgian Congo, which then had the world’s largest supply of uranium. He agreed. Szilard, “who was nothing if not obsessive,” according to biographer Jeremy Bernstein, wanted to reach President Roosevelt, and so through his connections at Columbia University, he contacted one of FDR’s economics advisers, Alexander Sachs, who agreed to carry a letter to the president if it had Einstein’s signature. By that point, Wigner had gone to California so Szilard got another Hungarian physicist with a driver’s license, Edward Teller, to go back out to Nassau Point. After completing two versions, a long one and a short one, Einstein signed them both on Aug. 9, warning the president about “extremely powerful bombs of a new type.”

By 1939, Einstein had come to regard the use of force as the only way to stop fascism—but he never worked on the Manhattan Project although his letter was its spark.

Sachs gave Einstein’s letter to Roosevelt on Oct. 11, a month after Hitler had invaded Poland. The next morning Roosevelt created the Advisory Committee on Uranium, naming Szilard, Wigner and Teller to it, but not Einstein, perhaps because FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, no friend of German Jews trying to emigrate, had viewed Einstein as a security risk because he’d previously proclaimed in Europe that “I am a militant pacifist” and he kept a large file on him once he came to America.

A man of peace, Einstein would have appreciated that, since the former Camp Upton’s reincarnation as a national laboratory in 1947, the BNL never did weapons research. For decades scientists there have been committed to exploring the inner workings of the atom to advance human understanding—although their research is always at the mercy of Congressional largesse and that’s never predictable.

According to his many biographers, Einstein—“the last of the great classical physicists”—may have not liked being in a classroom (in Germany his teachers called him a “dreamy” child) but he loved sharing the profound joy he found in physics, and that’s why he was determined to explain one of his theories to Rothman before he returned to the Institute of Advanced Studies at Princeton. After all, when Einstein published his relativity paper in 1905, he didn’t even have a Ph.D. and was working in a patent office.

Einstein’s goal with Rothman, as Rothman told his daughter, was to demonstrate to his friend Dr. Gustav Bucky, another esteemed physicist who’d come out to Nassau Point to visit him that summer, “that a layman, in fact a mere merchant, could comprehend these problems.” Rothman’s only stipulation was that the great scientist should not use math since he’d never gone past eighth grade. Einstein assured his friend it could be done. “You know, I use no instruments,” Einstein told him. “My tools are simply a pad and a pencil. This is all I have ever needed.”

What he’d make of BNL’s multi-million-dollar high tech tool for experimental physics can only be left for speculation. According to researchers familiar with his archives, Einstein never visited the lab.

What is known is that on a Sunday afternoon in 1939 the most famous scientist of the 20th century and the Southold department store owner spent three hours together wrestling with the problem: why a spinning rod contracts in the direction of its motion as it approaches the speed of light.

“I got nowhere in trying to grasp what he wanted me to,” Rothman recalled ruefully, and he lamented to Einstein that “the whole pad was full of mathematical symbols.” Einstein insisted that the math he was using was “quite trivial.” Rothman never understood the answer but he treasured the sheet that Einstein had covered in calculations, and his offspring later sold it for thousands of dollars to a collector.

The day before Einstein left the East End, Rothman came out to Nassau Point to see him off and he was presented with a new biography that had just come out, “Einstein: The Maker of Universes.” Einstein had inscribed it, in German: “May this book remind you of the happy times we spent together in the summer of 1939.” It was signed simply: “A. Einstein.”

Then, when Rothman took his hand to say good-bye, Einstein “put one arm affectionately around my shoulder and said, ‘You know, this has been one of the most beautiful summers of my whole life…’”

And to think it happened on Long Island.