On May 19, 2009, Nassau County’s Seventh Police Precinct received a report of a break in at John F. Kennedy High School in Bellmore. More than $3,000 worth of electronic equipment was stolen from its auditorium.

The case appeared open-and-shut: Surveillance video caught a student near the auditorium afterhours during the exact time of the theft. School employees reported witnessing the same student attempting to gain access to a restricted area at the school. An acquaintance of the student surrendered some of the stolen goods to the police, telling authorities his friend had given them to him.

Yet despite the compelling evidence, three independent sources within the Nassau County Police Department with privileged knowledge of the case’s inner details—who spoke with the Press on the condition of anonymity because they are barred from commenting on ongoing investigations—tell the Press the student, though identified, was never arrested. His father is a business associate of a little-known nonprofit organization called the Nassau County Police Department Foundation.

It’s no coincidence, the Press has learned. Internal police documents reviewed by the Press and interviews with more than a dozen current and former active and retired police officers, detectives and senior Nassau police officials outline a program that could reward the group’s members through preferential treatment that experts classify as questionable and unethical at best; pushing the limits of the very laws they were sworn to enforce at worst.

That was the lede of the Press’ March 31, 2011 cover story “Membership Has Its Privileges: Is the NCPD Selling Preferential Treatment?”

Without naming Nassau County Police Department (NCPD) benefactor Gary Parker or his son Zachary, the story detailed how the felony investigation into thefts at the school perpetrated by the latter was quashed, allegedly due to his father’s cozy relationship with members of the department’s top brass.

The article sparked a criminal investigation into the thefts by the Nassau County District Attorney’s Office, which resulted in grand jury indictments against the younger Parker on three felony counts in Oct. 2011: burglary, grand larceny and criminal possession of stolen property. He pled guilty to the burglary and was ordered to pay nearly $4,000 for equipment never returned.

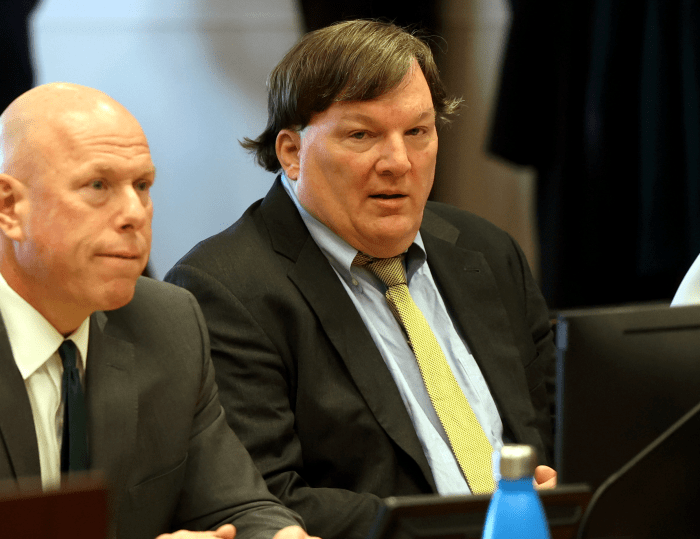

It also sparked a criminal investigation that resulted in a 10-count indictment naming NCPD’s third-highest-ranking official, former Second Deputy Commissioner William Flanagan, along with retired Det. Sgt. Alan Sharpe and former Deputy Chief of Patrol John Hunter on conspiracy and official misconduct charges. Flanagan was additionally charged with receiving reward for official misconduct in the second degree, a felony. Sharpe was additionally charged with offering a false instrument for filing. They all face prison terms if convicted.

Flanagan and Hunter retired less than 24 hours of turning themselves in to investigators shortly after sunrise on March 1, 2012; Sharpe had retired less than two months prior. Collectively their annual salaries totaled more than $540,000; their pensions remain intact despite the charges.

Flanagan, Hunter and Sharpe’s defense attorneys—Bruce A. Barket, William Petrillo and Anthony Grandinette, respectively—have contended their clients have done nothing wrong and a judge has granted them separate trials.

Flanagan told reporters the courtesies given to his friend Gary’s family were the same he’d afford any other member of the public. His trial began Jan. 15.

News of the indictments has been covered by nearly every media outlet in the region. The allegations strike at the heart of what public law enforcement servants are mandated and take an oath to do: serve and protect the citizenry and enforce its laws.

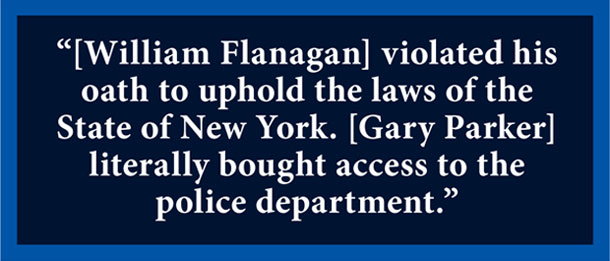

“[Flanagan] violated his oath to uphold the laws of the State of New York,” Assistant District Attorney Cristiana McSloy told jurors in her opening statement, adding that Gary Parker “literally bought access to the police department” with dinners, sporting events and other gifts.

What hasn’t been fully reported, however, are the complete details of what exactly went on behind the closed doors of Nassau County’s Finest in the hours, days and months following the May 18, 2009 break-in—and why despite the surveillance footage, admission by the perpetrator’s parents of their son’s thefts and a signed statement from the school’s principal calling for the student’s arrest, he remained free until our story.

The latest trial testimony fills in many of those blanks, along with providing new details and insights into the motives of the three former police officials and the culture existing within the department that enabled such events to transpire in the first place. It also raises more questions concerning the involvement other department higher-ups may have had in the alleged cover-up.

We now know, for example, that after reading the Press story, Gary Parker “panicked” and began deleting the many emails he had with Flanagan. Prosecutors contend the then-top cop did the same, and in those correspondences, he referred to Parker as “family.” We also know a bit more about the lavish dinners enjoyed by Nassau police’s top brass at top restaurants across Long Island and Manhattan, compliments of Parker, who testified the bills ranged from the hundreds to more than $1,200 each and were attended by not only Flanagan and Hunter, but also former Nassau Police Commissioner Lawrence Mulvey, and on at least one occasion, popular Fox News Channel cable TV host Bill O’Reilly. We also have, again from the mouth of Parker himself, descriptions of the police identification cards and “gold” badges doled out to foundation members—still a bone of contention with Nassau Police Benevolent Association President James Carver.

“When our guys pull over someone and they pull out an ID issued from one of these organizations they take a step back and don’t want to get themselves into any type of discipline,” he says. “They are afraid of taking some kind of action.”

“They shouldn’t have the shields,” blasts Carver. “That is the bottom line. If are doing it for the good of their heart, there is really no reason to issue somebody a shield, bottom line.”

Cristiana McSloy, in her opening statement at

former Nassau Second Deputy Commissioner

William Flanagan’s conspiracy trial Jan. 15

Regardless of what the jury finds, a Press examination of these latest revelations, court filings, recovered email correspondence between Gary Parker and the trio cited in the indictments and read aloud in court, police records, interviews with more than a dozen current and former NCPD officials, prosecutors, defense attorneys and reporting by this publication and others together paint, at the minimum, an indisputable portrait of how sworn members of the agency charged with protecting its citizenry and upholding its laws did everything in their power to protect and serve the interests of this wealthy police benefactor and friend.

Flanagan and Barket aren’t necessarily denying this, but arguing that all they were doing was returning stolen property to a crime victim, which they say is a core part of the police’s job. The gifts were coincidental, they contend. Prosecutors believe those actions (and inactions, namely the non-arrest of Zachary Parker) were criminal.

Our analysis identifies several key details jurors unfortunately won’t get to hear while weighing their decision, including profound discrepancies between prior statements of the defense, witness testimony and documented facts within the paper trail. So too does it uncover continued lapses in transparency regarding the public/private partnership that is the nonprofit police foundation.

The public would not know about any of these things, however, were it not for the unfortunate misdeeds of Zachary Parker—or our disclosure of a March 2010 internal police department-wide memo stating foundation members were to be treated differently should police personnel come across them during their regular duties.

Though prosecutors recently informed jurors Zachary Parker wouldn’t be testifying (he’s currently incarcerated at Lakeview Shock Incarceration in Brocton, NY following a slew of additional criminal charges, some still pending, since his burglary bust), his significance was not lost on the proceedings.

“You’re not going to see him in the courtroom, but his presence is everywhere,” said Nassau County Assistant District Attorney Cristiana McSloy.

Who was this troubled young man? Why didn’t the police ever arrest him? And just how high up does this scandal reach?

CAUGHT ON TAPE

When JFK High School Principal Lorraine Poppe learned the school’s projector was missing May 19, 2009, she believed she knew exactly who’d taken it: Zachary Parker, a senior at the time who had already been banned from school grounds without supervision afterhours due to several prior incidents regarding missing equipment.

When she gave a statement to Nassau’s Seventh Precinct to report its theft, she told Police Officer Samantha Sullivan as much. Sullivan initially jotted down Parker’s name on the ensuing police report then crossed it off because she wanted to keep the document objective for the investigating detectives, she testified. Additionally, a custodian saw Zachary in the area “trying to gain access to the area where the projector was being used,” she added.

JFK’s former assistant principal William Brennen testified he saw Parker on school surveillance video afterhours while he was banned “carrying a satchel containing something of a relative size to a projector.”

Brennen, who was in the school’s coaches’ offices the night of the projector theft, said those surveillance cameras were installed because of the prior thefts. He also saw Parker’s car in the back of the school and watched him enter through its gym entrance doors facing the football field. Brennen waited for Parker to exit the same doors after trying to keep an eye on him from afar, but Parker exited another set of doors unexpectedly, though was still caught on camera.

Jonathan Dell’Olio, dean of students, a coach, and 15-year English teacher at the school, testified that he had taken Parker under his wing and that “Zach and I knew each other well.”

He described Parker as “an integral part of setting up and breaking down school events.”

“[Zachary] earned the trust of the custodial staff, the athletic coordinator…he would be allowed to go fetch things that would be necessary to make the production work” until Brennen informed him of the afterhours ban, said Dell’Olio. “Zach was apart of most conversations dealing with technology because he was very good at it” and in turn knew where the cameras were placed after the thefts started—all outside, none inside, but with “some dead areas.”

The night of the theft he heard a custodian over Walkie-Talkies asking to allow “Zach” to the second floor and spied from afar, the dean continued. “I wanted to see what Zach was up to without him noticing me,” he said. After seeing Parker with a backpack walking toward the auditorium, he tried to intercept him, but he’d gone out a side exit. The next morning at 7:30 a.m., Brennen was in his office with IT aide Donna Hanna, who said the projector was missing. He told her about Parker’s visit the night before, informed Poppe and “then we went to the videotape.”

The police never viewed nor asked to view the surveillance tape, nor interview the eyewitness school personnel.

Parker, 18 years old at the time of the May 2009 break-in, had made no secret of his desire for expensive new sound equipment to add to his DJ rig. It was, in fact, evident to anyone who’d ever viewed his MySpace profile page, where Parker stated under his moniker “DJZeeMac” that he’d started spinning at camp in 2004, DJed sports events for JFK High School and boasted that he “was just recently employed by Nassau County Section 8 Sports to DJ all their postseason sporting events.”

“On my wish list as of now are a set of Mackie speakers, Xone 92 mixer, Denon CD deck, and the PCDJ DAC-3 controller (and flight case for it all to go into), all which’ll probably total up to about $2g’s,” he wrote.

Three days after the May 18 burglary, Zachary showed up at his friend Lothar Keller’s apartment in Franklin Square—his then-girlfriend also lived there. Earlier that month Parker had brought Keller a Dell laptop that he sold for $350. This time, Parker brought three more laptops and a projector.

“He just slapped ’em down on the table and said, ‘Look what I have,’” Keller told jurors.

The 24-year-old self-professed “gutterman” testified that later that day, while driving Zachary around, his father, Gary, called his son and was “bugging out on him,” so he dropped Zachary off at home. On the way back to his apartment, Keller got a call on his cell phone from “Dr. Jones”—Zachary Parker’s nickname. But it was Gary Parker on the other end.

Gary, partner at Manhattan-based Spielman Koenigsberg & Parker LLP Certified Public Accountants and an avid boater, states his company bio, was “a bit of a police buff,” according to ADA McSloy. He testified Jan. 29 that he’d been involved in police benevolence activities since the late 1980s, early 1990s, helping obtain nonprofit status for the Police Foundation of Nassau County—a group that had its nonprofit status revoked for failure to file required tax documents with the U.S. Internal Revenue Service and was separate from the Nassau County Police Department Foundation, former Commissioner Mulvey’s brainchild.

The elder Parker wined and dined Flanagan, Hunter and other Nassau police brass with “lunches and dinners”—totaling more than $17,000, according to a source close to the District Attorney’s Office investigation—and other gifts, charge court documents. He testified Jan. 28 about the meals—ranging from seafood and pasta smorgasbords at Uncle Bacala’s in New Hyde Park to top cuts of sirloin at Morton’s in Great Neck and Manhattan’s upscale Sparks Steak House—yet couldn’t recall who exactly attended a slew of feasts at Bacala’s. Flanagan, Hunter and Mulvey also attended barbeques at his house, he testified.

“He was screaming at me that I was in possession of stolen property, that I would be hearing from the police,” Keller said of his friend’s dad.

After he hung up, Keller called the person he’d sold the Dell laptop to, and then called the police, he testified, telling jurors he went to the Fifth Precinct with all the gear Zachary had given him to try and avoid “getting in trouble.” The clerk looked baffled when Keller told her it was all stolen property, he said, and was then interviewed by an officer.

“I told him that I had gotten all of these electronics from this kid Zachary Parker,” he said. “I didn’t want any part of it.” Keller signed a sworn statement and went home.

It wasn’t the last time his association with Parker would bring him trouble with the law, Keller testified.

Later that summer, Keller was cruising along in Parker’s car after they’d just finished smoking marijuana when a state trooper stopped them for speeding on Ocean Parkway.

Keller swallowed the remainder of their joint as the trooper approached, but testified that he and his friend ultimately had nothing to fear, because when Parker pulled out his license, the cop saw his “gold” badge in his wallet and said, “Have a good day.”

Zachary Parker had a history of getting out of trouble that any other person would not, court documents, deleted emails and testimony reveal.

PAPER TRAIL

Hunter, formerly the commander of the Highway Patrol Bureau and a close personal friend of Zachary’s father Gary, was “instrumental” in getting him out of multiple moving violations, state court documents—evident by the fact his license plate had been run by police at least 20 times yet he never received a citation, according to law enforcement sources close to the case.

He was also instrumental, say court filings, in getting Zachary a job within the police department in its Emergency Ambulance Bureau, a position created solely for him. Parker was 16 when he was hired by the NCPD.

Gary Parker testified that in August 2008 he and Hunter spoke about somehow getting Zachary a uniform. Parker’s hire had to be signed off by the NCPD, Nassau’s Office of Management and Budget and the County Executive’s office, according to the police department’s head of public information, Inspector Kenneth Lack. Parker further testified he reached out to another friend—the husband of Mulvey’s secretary—to help land his son the job.

“I asked a friend of mine…to help get my son a job’ with Nassau County Police Department,” he said. “I wanted him to get a part-time job…he wanted to become an EMT, it’s an area he likes and I thought it would be good experience.”

“He was a friend,” Parker testified, of Hunter.

Hunter helped get Zachary a ride-a-long, Gary testified, and the pair’s friendship was so strong, contends court documents, that Hunter even provided Parker with a police generator during a blackout.

It’s no surprise then, that when Hunter—who Gary Parker acknowledged to prosecutors attended annual barbeques at the Parker home and dinners at restaurants on Gary’s dime—learned of the complaint regarding Zachary, broke the normal chain of command for such investigations and inserted himself into the matter to prevent arrest, contends McSloy.

Since Zachary was a department employee, when the commander of the Seventh Precinct Detective Squad received the initial report from Poppe, the head of the squad, in accordance with proper protocol, referred the matter to the NCPD Internal Affairs Unit (IAU).

Yet “within a day,” Hunter, who was not in the detective squad chain of command, “called the squad commander to let her know that IAU would not be investigating the matter despite the suspect’s employment with the department,” say the filings, despite having “no supervisory authority over either the squad or IAU.” Hunter also requested “that he be kept informed of the status of the felony investigation,” contend prosecutors.

The police commissioner is routinely briefed by internal affairs, according to Lack, who was also named by Parker as an attendee at a $2,346.47 feast at Spark’s, alongside Flanagan, Mulvey and others.

On May 22, Gary received a call and invitation from Sharpe to come to the Seventh Precinct and talk about his son, he testified. Sharpe showed him the equipment dropped off by Keller and informed him his son was a suspect—one computer actually having “ZeeMac” scrawled across it in marker. Parker admitted his son’s guilt, he said, and name-dropped a few people he knew at NCPD, though told the jury he didn’t recall who he mentioned.

Sharpe didn’t take an official statement nor voucher the stolen merchandise, which is typical police procedure in any investigation, and instead suggested Parker visit Poppe. (Sharpe’s also accused of entering the department’s computer system and falsely stating that Poppe did not want Zachary arrested for the thefts.)

“I told [Gary] that I was disappointed in his son,” testified the principal. “I told him the plan was to have Zachary arrested.”

She also told him Zachary would be suspended, banned from attending the prom, senior events and graduation. The next day, Parker asked Hunter to meet at Colony Diner in East Meadow and returned his son’s NCPD identification and uniform.

Parker told Hunter he was trying to work with the school, he testified, and “in passing” told him to “put in a good word” with Sharpe. They hugged each other before leaving.

Later that week Parker bought his son a same-day ticket to visit his grandparents in Florida and Hunter, in a recovered email, wrote him “Anything I can do to help, let me know.”

Gary, in another deleted emailed to Hunter at the end of the month, requested the squad “lay low,” states the documents, to which the deputy chief assured him he would “make sure that is done” and then made arrangements to return the property to the school.

“Thank you for being a great person and friend,” replied Parker.

“[A]s you taught me that is what friends are for!” answered Hunter.

Hunter also reached out to a nephew of Poppe’s who was a NCPD canine officer and asked he help get the principal to drop the charges. He refused.

So did Poppe, multiple times, despite not only repeated attempts through May and June by police detectives directed by Hunter and Sharpe to have her sign a withdrawal of prosecution form, emails, court filings and testimony show—but also an intimidating visit at 1 a.m. by one of Barket’s investigators, a tidbit Barket convinced the judge not to allow jurors to hear.

“We wanted to have Zachary arrested,” she told jurors Jan. 22, noting that the detectives who repeatedly tried to get her to withdraw charges “never asked me for a copy of the video.”

Parker then reached out to another friend, then-sergeant in the NCPD’s Asset Forfeiture Unit and a close friend of then-Commissioner Mulvey, William Flanagan.

Or as Parker called him at the time, “Bill.”

“BILL”

Despite repeated questioning by prosecutors, Parker insisted he could not for the life of him remember when or how he met Flanagan, or how frequently he and other top police brass, such as former commissioner Mulvey, attended his dinner gatherings.

The judge denied a request by ADA Bernadette Ford for Parker to be recognized as a hostile witness for his forgetfulness; his memory miraculously returning upon his cross-examination by Barket the following day.

Parker did state that he was on a first-name basis with Flanagan by May 2009—though court testimony and recovered emails between the two suggest a much closer relationship with the former deputy commissioner and other top police brass.

Just days before the May 18, 2009 JFK High School theft, for example, Parker offered Flanagan via another deleted email Yankees tickets and access to an “outdoor seating area…custom designed with 1,300 cushioned seats with padded backs that offer an extraordinary stadium experience.” That emailed offer, the filing states, also noted that Flanagan would have “access to the Terrace Level Outdoor Suite Lounge, a separate climate-controlled indoor environment that offers a multitude of exclusive perks, including access to private restrooms, high-definition TVs, a variety of menu options, and a four-sided cocktail bar that delivers an exceptional selection of beverages.”

Parker sent a similar email to then-Police Commissioner Mulvey and current first deputy commissioner Thomas Krumpter and, too, leaving the tickets in an envelope for Flanagan at the Seventh Precinct, he said—describing them as “lousy seats” to prosecutors during direct examination.

The revelations kneecap Barket’s prior adamant assertions to the press that his client didn’t even know Gary Parker at the time of his son’s May 18, 2009 theft.

“It is to some degree mindboggling why it is Deputy Commissioner Flanagan was charged at all,” he professed to reporters outside the courtroom on the morning of their indictment March 1. “He did not even know Zachary Parker or Gary Parker on the date of the crime. He literally had nothing at all to do with the decision to arrest or not arrest Mr. Parker in May of 2009.”

“My client did not know Gary Parker or Zachary Parker at the time of the commission of this crime,” he repeated. “He had no role in whether or not Mr. Parker should be arrested or should not be arrested in May of 2009.

After that, well after that, they became acquainted, they are friends, they socialized together, they go to dinner together, their wives have met, they’ve been to each others’ house. Because they met and liked each other. I think they met at a golf tournament.

“If it weren’t for golf tournaments I wouldn’t have any friends at all,” he joked when a reporter asked if their relationship at seemed at least a little conspicuous.

“Honest to God, I didn’t follow your reasoning,” he insisted. “Is it suspicious that individuals make friends and that police officers have friends and that deputy commissioners have friends? No.”

It’s what sworn police officers and deputy commissioners do for those “friends,” and what those “friends” do in return, that has prosecutors sounding the alarm.

Following Hunter and Sharpe’s failed attempts to return the stolen equipment to JFK and Poppe’s repeated resistance to signing a withdrawal of prosecution, Parker met with Flanagan, according to his testimony, while Flanagan provided security for the Bethpage U.S. Golf Open June 18 and asked him for advice.

“I understood that he had a close relationship with the police commissioner,” he told prosecutors, describing as his logic: “When the school got the property back the matter would be closed.”

“He was undertaking something on his own,” Parker said of Flanagan.

ADA Bernadette Ford had Parker read aloud for jurors a July 16 email he sent to Flanagan that prosecutors recovered after Parker deleted it—a heartfelt thank-you to Flanagan.

“Just the fact that you’re stepping up to the plate is appreciated,” he read. “I certainly realize that they [JFK] hold all the cards.”

“What did you want William Flanagan to do when you wrote this email?” Ford asked. “I’m not really quite sure,” he replied.

Flanagan emailed Parker June 23 that he had “put pieces in motion,” and according to court documents, “made numerous attempts to get the stolen property returned to the school…despite the school’s insistence several days earlier that it would not withdraw criminal charges against Parker’s son.

In another email in mid-August, Flanagan told Parker he had “stayed in contact with the squad supervisor” and that the squad supervisor was “aware of the importance” of getting the stolen property returned, says court documents, and in another assured him “it’ll happen.”

In early September, Flanagan informed Parker by email that the equipment was successfully returned—though Poppe still refused to sign a withdrawal of prosecution.

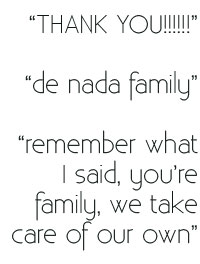

Ford has Parker read back his response and number of explanation points he included: “THANK YOU!!!!!!”

He also read and translated Flanagan’s response: “de nada family.”

Parker testified that the following day his wife sent two $100 Morton’s gift cards, a flashlight and a card to Flanagan, who replied that the gifts were “[o]ver the top” in a deleted email recovered by forensic technicians.

He also testified that Flanagan, who was promoted to deputy commissioner two weeks after their talk at the U.S. Open, asked Parker to join the foundation in spring or fall 2010. He served as a board member from March 2010 until his resignation on April 1, 2011, a day after the Press article’s publication—and immediately after discussing concerns that his son would be arrested with Flanagan and the nonprofit’s board. That prompting Flanagan to email him: “remember what I said, you’re family, we take care of our own.”

The same day, following calls from Krumpter, Flanagan, foundation board member and assistant commissioner Robert Codignotto and “maybe” Mulvey, he testified, he began cleansing his computer of emails to NCPD officials.

“I deleted them,” he said. “It was probably morally the wrong thing to do.”

Parker testified he’d received identification cards and a gold shield with a blue inset that read “Director” as a member of the group.

He also told prosecutors that a year after Flanagan helped get his son’s stolen equipment returned, the deputy commissioner asked him to help get him an early release of a Tag Heuer “Aqua Racer” watch at a wholesale rate; one of Parker’s clients being French luxury goods conglomerate Louis Vuitton Moet Hennessy (LVMH), which includes the high-end watchmaker. Instead of paying for the uber-prestigious timepiece—which can cost several thousands dollars at retail and are heralded by Cameron Diaz, Leonardo DiCaprio and Maria Sharapova, to name a few of the line’s celebrity “ambassadors.”

Parker testified he got it for $1,510.16—the 50-percent-off rate exclusive to the company’s friends and relatives program—sent it to Flanagan, and told him to write a check to the foundation as payment.

Time is something that his son Zachary has a good deal of now, and may have even more of in the near future, since he’s also facing drug-related charges in Florida.

A jury will decide whether Flanagan, Hunter and Sharpe receive time as well.