The lights dimmed and suddenly the packed Nassau Coliseum resounded with the opening chords of the 2001: Space Odyssey theme. Elvis Presley was in the house.

The fans roared as the King of Rock and Roll took center stage. Their camera bulbs sparkled like diamonds in the arena darkness and radiated off Elvis’ rhinestone jumpsuit.

“I remember all the lights flashing as he was coming out,” says Ellen Granelli, who was one of the lucky ones. “He had the audience in the palm of his hand for the entire time.”

Granelli, who works at the Northport library, saw Elvis at Madison Square Garden in June 1972—the only time he ever played in Manhattan besides the Ed Sullivan Theater—and both times he came to Uniondale in June 1973 and July 1975. The three shows basically followed the same set list, but she didn’t mind “because it was Elvis! You wanted to be there!”

(Photo by Ron Galella/WireImage)

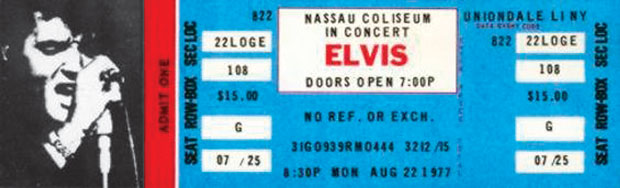

Granelli was in her 20s then—today her three kids are in their 30s. She had tickets to see Elvis in August 1977 with her new husband as well as her girlfriend Mary Jo, who’d been her companion at the previous concerts. They never got the chance. She and her husband were driving through the mountains of Maine on vacation when Elvis was all they heard on their car radio. Strange, they thought, since he hadn’t had a top 10 hit in quite a while.

“This isn’t good!” Granelli remembers thinking. Sadly, she was right.

“I was talking to my children the other night…and I said I saw the older Elvis, and then I stopped myself!” she says. “Older Elvis! He died at 42—that’s not old!”

On Aug. 16, 1977, less than a week before Elvis was to appear at the Coliseum—his first venue on the next leg of his tour that year—his girlfriend at the time, Ginger Alden, found him lying face-down on the shag carpet of his bathroom at Graceland, his famous mansion on Elvis Presley Boulevard in Memphis.

Somewhere in Granelli’s Northport home are her unused tickets. Her kids tell her they’ve seen them there and she’s sure she hasn’t thrown them away. Her Elvis collection, which includes “every album” (some 33 recordings by her reckoning), is up in the attic, but she doesn’t play his songs much these days, in part because they’re on vinyl. Unlike a later TV generation who endured Elvis’ egregious movies broadcast in the Sixties, Granelli got her first look at “Elvis the Pelvis” (as the puritanical press pilloried him at the time) when he appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1956.

“I was a little girl—I was only nine,” she says with a laugh. “That’s where it all started. From the earlier years I thought he was just magnificent, charismatic and very talented.” But she had to wait to see Elvis perform live, and she grabbed every chance she could get, even though it was obvious that the Elvis of the Seventies wasn’t the same performer who’d set the rock and roll world ablaze in the 1950s.

“He had a magnificent presence, even at that stage, that just kind of drew you in and took you to another place,” she says. “It was still Elvis, and it was still his voice.”

She and her girlfriend never made it to the front of the stage where Elvis would ceremonially shed scarf after scarf to the adoring female fans reaching out to him, but it didn’t matter to Granelli. “If you’re a true fan, you understand that you can be in the zone in the last seat in the last row,” she says.

On that fateful August morning in 1977 Steve Prisco—today Sam Ash Music’s marketing director—was driving to a ticket-scalper on Long Island to get front-row seats for the Nassau Coliseum show when he heard the news: The King was dead.

A young guitarist growing up in Huntington Station, Prisco had acquired a taste for rockabilly music after looking through his older brothers’ record collections and getting turned on to the tracks Elvis had recorded at Sam Phillips’ Sun Studios in Memphis.

“The power of that music really grabbed me,” he says. “Up to that point, Elvis was just the guy in those afternoon movies.”

Prisco’s first guitar teacher was from Tennessee and had moved in right across the street. “He was a real good ole boy,” Prisco recalls. The teacher asked him who his favorite guitarist was. Prisco had read that the Young Rascals’ guitarist Gene Cornish had revered Scotty Moore, so Prisco repeated the name. “He looks at me, like, ‘Really?!’” Prisco recalls. “I had no idea who Scotty Moore was.” A few years later, he learned that Moore was the great sideman in Elvis’ Sun sessions, and so those seminal riffs he’d been learning in Huntington ran very deep indeed.

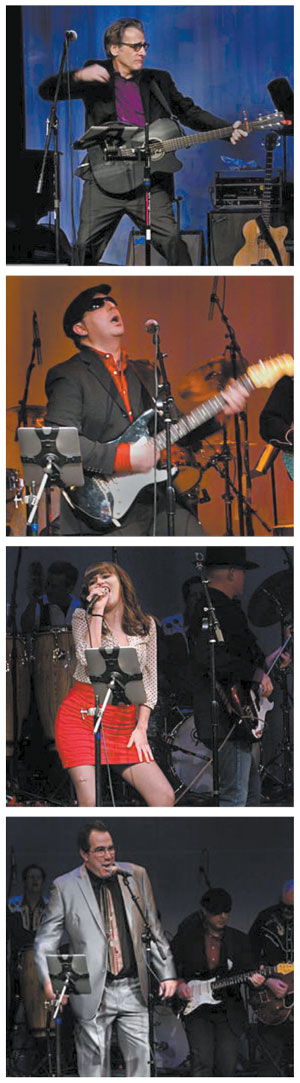

These days, through the New York Roots Music Association—NYRMA for short—Prisco has been the front man for “The Elvis Show,” Long Island’s longest-running Elvis tribute and charity event, which has raised more than $50,000 for food pantries over two decades. For the last three years in a row, they’ve sold out the YMCA Boulton Center for the Performing Arts in Bay Shore.

Prisco got the idea for the first show when he realized that his rockabilly trio was going to be playing on Elvis’ Jan. 8th birthday.

“We had a lot of friends who’d come down to see us—friends from other bands—and I always enjoyed having people come up on stage,” he says. “So that night I spread the word around that ‘Hey, we’re going to do a bunch of Elvis stuff, so come on down and come up and sing a song.’”

It clicked, and the next year he decided to ask people to bring canned food to donate to local pantries for the hungry and homeless. And so the event grew from a little bar in Huntington to where it is today—with a hiatus in the ’90s—and it’s been going strong eight years in a row with dozens of performers. But it was always about Elvis and his songs. The cardinal rule, Prisco said, was: “No Elvis impersonators!” He understands that some fans fixate on the “whole mythology and campiness and that whole insane side” of the Elvis image, and that “the impersonators play into that,” but, for Prisco and his peers, it’s about being “true to the vibe.”

No matter how his career was going on stage, Elvis always had his standards, according to his wife, Priscilla Presley, who divorced him in October 1973. As she wrote in her memoir, he “couldn’t abide singers who were, in his words, ‘all technique and no emotional feeling,’ and in this category he firmly placed Mel Torme and Robert Goulet. They were both responsible for two television sets being blown away with a .357 Magnum.”

The recent NYRMA event in January delved into Elvis’ “deep catalogue and some odd-ball stuff,” Prisco says, but the music could stand on its own. “I think if you didn’t know it was an Elvis show, you would still have enjoyed it because of the level of the performances and the musicianship.”

They did the King proud—and, in that spirit, it’s worth recalling how much the New York Times’ then-top music critic, John Rockwell, appreciated seeing and hearing Elvis himself when he last performed on Long Island almost 40 years ago.

“Mr. Presley can still rock, and he felt like rocking a refreshing lot of the time Saturday at the Nassau Coliseum,” the critic wrote on July 21, 1975. “When this observer last saw Mr. Presley, it was also the Nassau Coliseum, two summers ago. Then he was fat, lazy and ineffectual. On Saturday he was still fat—fatter than ever, a blown-up cartoon of his spare 1950s toughness. But he wasn’t lazy, and he most certainly wasn’t ineffectual.”

Granelli, who was also there that day, would no doubt agree with Rockwell’s assessment.

“It appeared to me he had the same charisma that he had in the ‘50s and the early ‘60s but he was almost a caricature of himself in the performance,” she says. She blamed his management, Colonel Tom Parker in particular. “I don’t think [Elvis] was any longer true to who he really was,” she says. “He was what they were telling him he had to be.”

Like many an Elvis afficionado, she believes he had tremendous talent but no coping skills to fend off the freeloaders.

“He was the son of a sharecropper,” she says. “Where would he have learned any business acumen? So once Colonel Parker got into the picture, I think that started out to be a good thing but ultimately destroyed him.”

Prisco says that though Parker took 50 percent of Elvis’ share, the performer never lacked anything he wanted—and he shouldn’t be held blameless for decisions that in retrospect limited his career, let alone his life. As for what Elvis achieved, Prisco believes that rock and roll really began when Elvis recorded “Mystery Train” in 1955.

“That was it,” Prisco says. “Nothing had sounded truly like that before.”

As Elvis profoundly changed American music, so too has the industry changed irrevocably—and Prisco believes there’s no going back to the days of “those big bangs—Sinatra, Elvis, the Beatles and, some people will say, Michael Jackson—that’s not going to happen anymore the way everything’s so fragmented now and so immediate. He’ll always have that.”

Elvis has left the building, never to return, but his music is still rocking the halls.