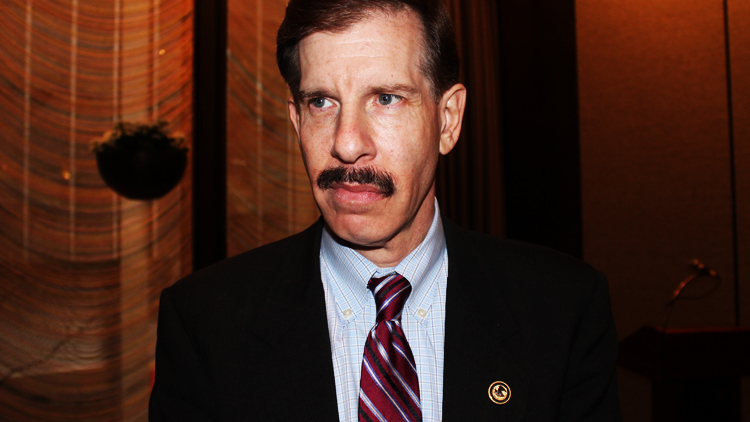

For a man who’s devoted nearly 30 years of his life hounding the despicable men and women who’ve committed crimes against humanity, Eli Rosenbaum doesn’t look so menacing.

Given the choice, he’d rather watch the Yankees or see a comedy than sit through another Hollywood movie about the horrors of the Holocaust. He’s been living with that gruesome reality almost 24/7 ever since the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Special Investigations hired him out of Harvard Law School in 1980.

Today the 57-year-old Long Island native is the director of the human rights and special prosecutions section, making him the Justice Department’s longest-running investigator of human rights violators living in the United States.

“So my entire career is really a summer internship gone awry!” he says with a grin.

There’s a kindness in his brown eyes that belies the evil he’s had to face. He helped deport Boleslavs Maikovskis, a Nazi war criminal living in Mineola, and Karl Linnas, a former concentration camp commander living in Greenlawn. Because nature has finally enacted a “biological solution” to that Nazi generation, his section is now pursuing war criminals from the likes of Bosnia, Guatemala and Rwanda, who think they’ve found a safe haven here. His message to them: “You’ll have to be looking over your shoulder for the rest of your life.”

Growing up “on the south side of Old Country Road in Westbury,” attending high school in East Meadow, and studying Hebrew three days a week, it’s surprising how little Rosenbaum knew about the genocide of World War II until one Sunday afternoon on his family’s black and white TV he saw a dramatization of the Nuremberg Trials by Peter Weiss, a German playwright. Rosenbaum couldn’t have been more than 12.

“The Holocaust wasn’t spoken about in my household—it was too painful for my parents,” he recalls. They had both fled Germany before the war.

But Rosenbaum’s father did return, wearing a U.S. Army uniform. One winter some 25 years after the war, Eli and his dad were driving through a blizzard when his father casually mentioned that he had been one of the first Americans to report on Dachau after its liberation in April 1945.

“I said, ‘Well, what did you see?’ I’m looking out at the road, and I didn’t hear anything. Finally I look at my father, and I see that his eyes have welled with tears. His mouth is open like he wants to speak but he can’t do it. He’s crying…To the day he died, he never told me.”

He found out for himself. Today, a father, Rosenbaum credits his wife of 25 years, Cynthia, who also has a law degree, for keeping him balanced. “She keeps me sane despite the awful stuff that I have to deal with—the subject matter of my work.”

Recently Rosenbaum was in Manhattan sharing the dais at the Four Seasons with Sara Bloomfield, executive director of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., which was celebrating its 20th anniversary—and has been an invaluable resource for Rosenbaum’s investigations.

The Nazis, it turns out, expecting they would win the war and rule for 1,000 years, kept meticulous records.

“We’ve done the best job of any law enforcement agency in the world in hunting these people down,” he says. “I like to think that this effort is carried out for the victims who perished and the victims who survived.”