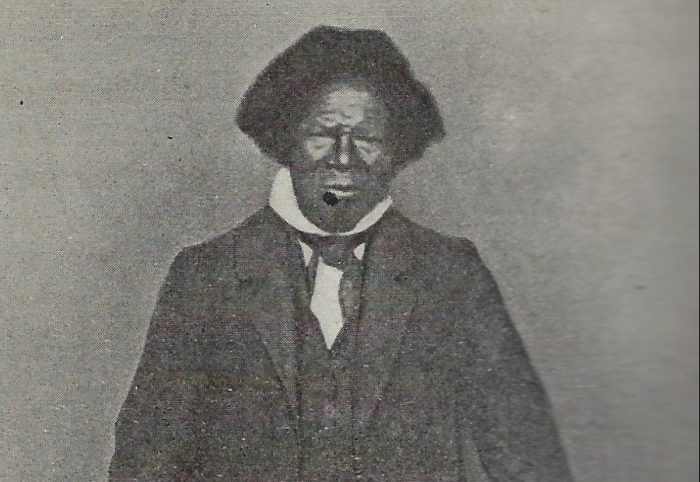

Thomas Dale stumbled blindly with his hands outstretched in front of him through the engulfing thick white cloud of dust, debris and human remains rolling through Lower Manhattan in the moments following the World Trade Center’s collapse.

Walking slowly, desperately hoping to reach a nearby school, the New York City Police Department veteran with 43 years on the job did his best not to fall down.

Out of the darkness someone had handed him a moist towel to help him breathe.

During a lengthy and exceptionally candid recent interview with the Press, Dale admitted to being scared, even “petrified,” yet like so many other brave first responders on the scene that day, he stuck it out, both accepting and giving orders—orders that undoubtedly helped save lives.

Sept. 11, 2001 was a defining and life-changing moment for the now-63-year-old, he says, and has forever shaped his outlook on life and the way in which he handles his job—which since his December 2011 appointment by Nassau County Executive Ed Mangano, has been heading the Nassau County Police Department, an agency that for the past several years has been the subject of not only an unprecedented downsizing, but several high-profile scandals.

Dale has been charged with cleaning up the mess.

“I almost died that day and I felt a lot different toward people after that day,” he confides, following a pause. “I saw tragedy that day and I saw people working with one another that I had never seen in my lifetime. The entire city, the entire Island, the entire United States—we worked together,” he recalls.

As much as a team player the former NYPD chief of personnel is, Dale’s not afraid to go it alone, something he’s had to do since nearly his first day at the helm—whether in front of the county legislature defending Mangano’s controversial plan to shutter half its precincts (to jeers from even “people who worked for me,” he says), or taking it upon himself last month to travel upstate to personally inform 21-year-old Hofstra University student Andrea Rebello’s parents that their daughter was accidentally killed by one of his officers May 17.

“It was the right thing to do,” he says of his visit to Tarrytown. “I’m the head guy. I thought that’s what a man should do.”

“The investigation is going on as we speak,” he continues, “we’re not finished with it. Every time there is a shooting we want to go through the procedure: Can we do something not to shoot? Can we make it better? This one is more exaggerated because of the seriousness of it and you always try to find if there is something we can do better.”

“Doing better” could be the mission statement of Dale’s administration thus far. Almost immediately upon his appointment he’d been thrust into the hot seat.

Dale was tapped shortly after New York State Inspector General Ellen Biben issued a report on the department’s troubled crime lab, which in 2010 became the only such laboratory in the nation to be put on probation following a scathing accreditation agency inspection report that November highlighting 26 areas of noncompliance with universally accepted standards. (It’s still closed and officials at the time had put the cost for outside testing and analysis of narcotics, blood and ballistics at $100,000 per month.)

“When I got here I found a lot of problems that I don’t think people thought about when they said, ‘Just close the lab,’” he says. “We are the people that bring the product in. We bring the evidence in here every day, the fingerprints, the blood sample, DNA. These are the other things. What are we going to do with it if we don’t have a lab to deal with it? Who do we give it to? There was no one to give it to.”

Dale appointed his new deputy commissioner to deal with “this very complicated issue.”

His goal is to have the lab completely outside the purview of the police department.

“It just doesn’t make sense anymore,” he says, “why have officers in there? You can have civilians who went to school for that. Put a sergeant in there and the sergeant gets promoted. I have an evidence management team that has set up a report every month on every piece of evidence.”

Dale hopes to stop sending out their evidence to numerous different places including Pennsylvania, Westchester and Texas, and to set up a complete lab in the county medical examiner’s office.

Three months on the job, Dale had to handle a different type of scandal. A March 31, 2011 Press investigation into the department and nonprofit Nassau County Police Department Foundation had resulted in a probe by the Nassau District Attorney’s Office and the indictment of three of the county’s top former cops a year later for their roles in covering up a burglary committed by a wealthy foundation donor’s son.

Former Nassau Police Second Deputy Commissioner William Flanagan was convicted of conspiracy and official misconduct this February. Ex-Deputy Chief of Patrol John Hunter pleaded guilty last month to the same charges. Retired Det. Sgt. Alan Sharpe’s next court date is June 26.

After reading our series and subsequent agency reports, Dale was swift with his response.

“I realized I could do some things right away,” he says. “So one thing was they [foundation members and donors] all have these special ID cards. I asked them and they agreed from now on everybody has the same ID card. We do have a lot of civilians with ID cards. We have an Explorer board that have ID cards, we have a foundation board, we have some honorary surgeons that we deal with. A lot of people who have ID cards, but I want everybody’s to be the same so there’s no one special.”

In addition to the police IDs the members had police shields, though putting the kibosh on those wasn’t going to be that easy.

“I can’t tell them not to buy a shield,” he explains. “I don’t give them a shield, they buy it themselves. I can’t stop it. I said, ‘Guys, you should not be showing them, that’s not appropriate.’”

Dale did “immediately” cancel a department-wide order requesting officers verify foundation membership, however.

“We revoked that order immediately,” he says, adding that the group’s members no longer have free access into police headquarters, nor an office there, as was the situation under his predecessor former Nassau Police Commissioner Lawrence Mulvey (who retired the following day of our series’ first installment). Dale closed that down, too.

After researching other foundations, Dale says he told members that there had to be a separation between him and the organization. Regarding the larger issue of monetary donations often coming with strings attached, Dale says:

“There are two ways that we are approaching it. One way is basically what has happened, which scared the pants off of most everybody here. The other way is internally. What I do now is every day I read every complaint that comes in. If someone makes a complaint anywhere—Internet, any government office, or through us—I get it and I read it. I get briefed from our internal affairs on a lot of the cases that were always handled out there. Now they are not handled by them, they are handled by me.”

As a result of his changes, Dale believes that “the guys out there on the street know that I mean business. These were very serious cases that I have been dealing with since I got here. Can I ever prevent somebody not to call up somebody? I told them, I met them in person and spoke to them—man to man, woman to woman—‘If you do this, you’re going to get in trouble.’”

“I have to do everything in my power to prevent that, but it’s a very difficult thing to prevent, very difficult. It would be naïve to say it would never happen again.”

Dale says one of his goals was to reinforce the authority of supervisors. Prior to his taking office, he said the route was a cop would go to the union, who would go to the government and do an end-run around their supervisors, leaving those supervisors without any authority. He was able, he says, to get a “bill passed where I am in charge of discipline.” Now, when a cop is put on disciplinary probation, a supervisor can write them up and they may be terminated. “I have empowered the sergeants and lieutenants. They had no power before—I needed to empower my bosses.”

“They weren’t being supported so I’ve supported them,” he continues. “Now they know when they do something they’re going to have to pay the price. I’m not looking to fire anybody. I’m looking to just maintain discipline. We don’t have enough people to go around firing everybody, that’s just crazy. Everybody is saying, ‘He is firing everybody.’ I’m not firing everybody that comes before me. You don’t have to agree to with what I said. You can go to trial. You can do this you can do that. They don’t want to go to trial.”

The department, according to numerous sources, had become lax when it came to discipline. Dale said his job was to turn that around. He said while he couldn’t discuss specific cases, “I have been strict.” He added that “A couple of people have been terminated.”

Some of the cases he has dealt with, he says, include an officer shoplifting, officers using internal records to run plates for friends, officers involved in the Jo’Anna Bird domestic violence murder case and several “Romeo” cases, whereby officers were involved with women while on the job.

“There was some pretty serious stuff,” he says.

Dale’s been spearheading the internal housecleaning while also keeping his eye on what he says is his main priority: crime. That is no easy task with a depleted department and a shortage of cops.

“Crime is our number-one issue and I think the best way to attack it is to be smart, as we don’t have the personnel,” he says.

Doing more with less has become a major challenge for Dale. He believes the biggest difference between Nassau County and New York City police departments is “we don’t have enough people.”

The city can direct personnel to problem areas, whereas Nassau doesn’t have the manpower to do so, he explains.

“We don’t have that luxury,” he says. “We have to do it with intelligence policing that we developed to try to be smarter with what we got.”

“Omnipresence is our goal but we are so short right now,” he adds. “I am hoping as time goes by and things get better and we start hiring a little bit more, I think it will get better. I know it will get better. I know it’s getting better.”

The grandfather of four doesn’t know how long he will keep working, but one thing he is sure of: “In 1970 my first day on the police department I got up and I had like a fire in my belly and now at 63 years old I still feel the same thing when I go to work.”

When that feeling stops, he stops, he says.

“Now I’m in a position where I can do something some really good things,” he says. “I’ve seen so much, I could use all that experience, and I really try to do that in Nassau County. I have family here, I pay taxes like everybody else and I want to make sure that we get a good product.”

Dale thinks back to that tragic day in September 2001 for inspiration and guidance.

“There was no crime, we were working for a purpose, together, and I’ve accepted that into my own life,” he says. “That is the way we should be all the time.”

He has the towel the stranger handed him during those darkest of hours to prove it.