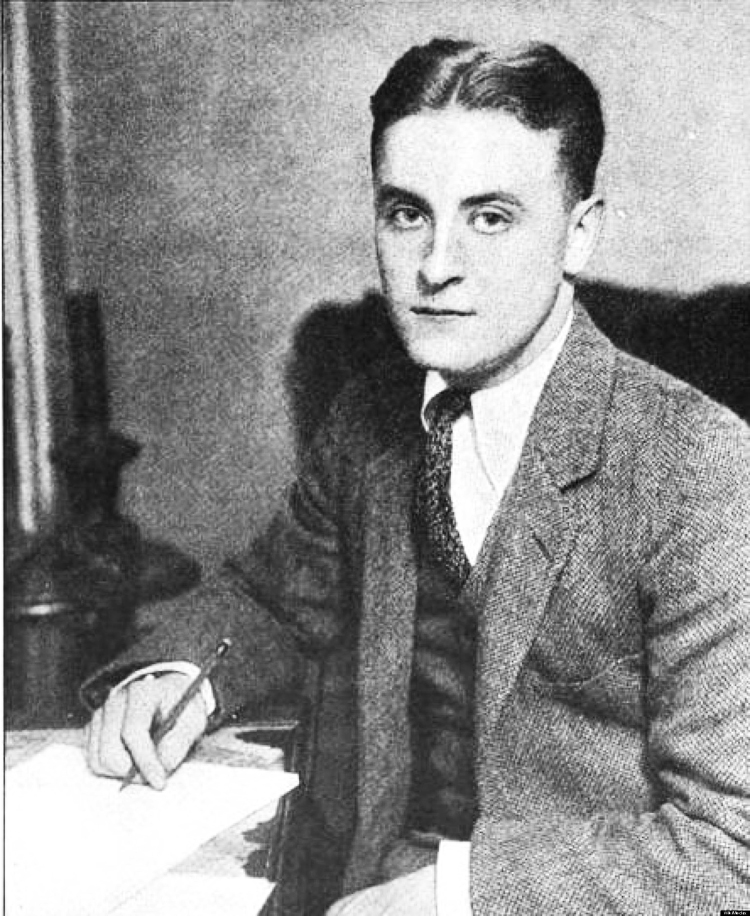

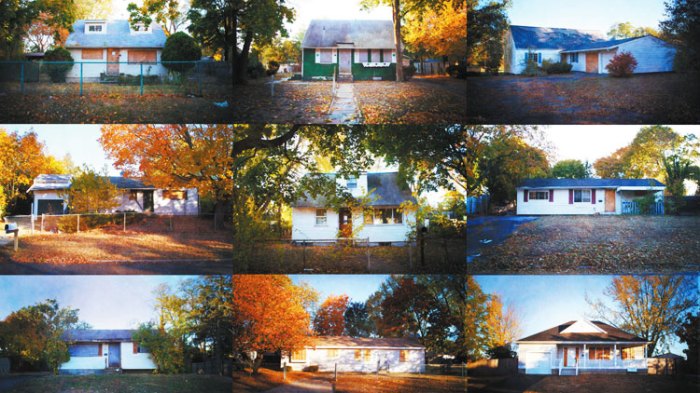

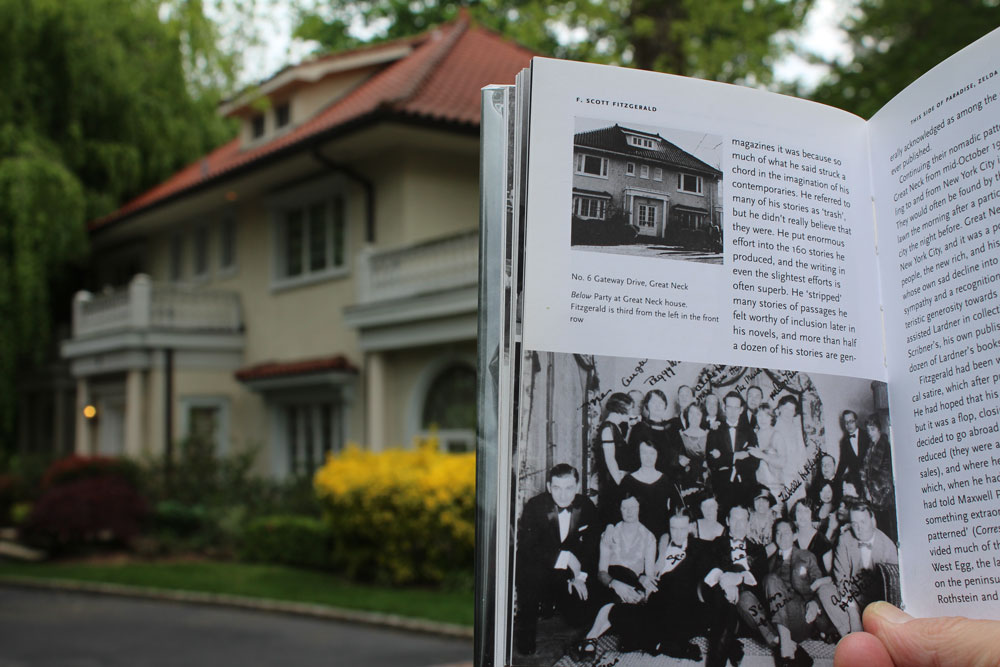

F. Scott Fitzgerald could recall his Great Neck address, drunk or sober. But these days he might need a second or two to recognize the place his wife Zelda once called their “nifty little Babbitt-house,” back when Sinclair Lewis’ biting satire about American conformity was all the rage among the cognoscenti.

Today the two-story cream-colored stucco mansion has a terra cotta roof and a small balcony with a white colonnade above the front door, exuding an elegance that the place probably didn’t have when the young Fitzgerald family rented it in 1922 while their daughter Scottie was still a baby.

The landscaping is likely more lush and well-manicured than when he and his wife passed out on the front lawn after somehow driving home in their second-hand Rolls from a long night of partying at The Plaza only to be awakened by their housekeeper in the cold morning light. These days nobody could navigate 20 miles of Northern Boulevard with a blood-alcohol level like theirs without running into the police or worse.

Perhaps the biggest change is that the studio above the garage where Fitzgerald cranked out his lucrative short stories for The Saturday Evening Post and began a first draft of what would become The Great Gatsby is now connected seamlessly to the main building. It can no longer offer the kind of solitude he used to find there when he had to get away from what Zelda later described as the “disorder and quarrels.”

This Gatsby connection was a surprise to the high school sophomore now residing with his family on Gateway Drive.

“Wow, I didn’t know that!” he tells me, preferring that his name not appear in print. He’d just been watching SportsCenter on ESPN when this reporter recently showed up at his door.

He admitted that, like most adolescent American boys, he hadn’t yet read the classic novel because it hadn’t been assigned in school.

“Maybe I’ll see the movie,” he says, unconvincingly.

He wouldn’t have to go very far to catch it, if he was so inclined. A new Gatsby film has just come out—marking the fourth time since 1926 that someone has tried to capture cinematically Fitzgerald’s lyrical prose that retells the tragic tale of one self-made man’s obsession with the American Dream.

The book has hit the bestseller list—something it never did while Fitzgerald was alive. The movie reviews, so far, have been mixed at best.

“You don’t realize just how much misguided damage can be done to a great novel until it is vaporized by a pretentious hack like boneheaded Australian director Baz Luhrmann,” wrote Rex Reed in The New York Observer.

Luhrmann (Moulin Rouge and Romeo + Juliet) spent more than a $100 million to try what has never succeeded before: turn this literary masterpiece into a compelling movie. But he gave it his best shot, this time in 3-D with a contemporary soundtrack produced by Jay-Z.

Days before The Great Gatsby opened nationwide in May, Luhrmann, a soft-spoken, slender figure with silver hair, was on hand at the refurbished Soundview Cinemas in Port Washington where Warner Brothers was hosting a special screening. With earnestness he told me that he regards Gatsby as “America’s Hamlet.”

Asked whether his latest cinematic creation was “The Greatest Gatsby” yet made, the director demurred but he defended his version.

“It’s actually an incredible reflection of this time we’re in!” he says, standing on the red carpet rolled out in the lobby.

After the film, presented by the Gold Coast Arts Center and the Town of North Hempstead on May 8th, invited guests were going to an exclusive “Gatsby-themed” party at Sands Point Preserve. Luhrmann’s lead, Leonardo DiCaprio, who plays Jay Gatsby with magnetic fervor, did not attend the screening.

His Oscar-worthy performance is arguably the only bright spot in an otherwise “mediocre” film, according to Hofstra English professor Ruth Prigozy, co-founder of the F. Scott Fitzgerald Society. “It was all the parties—you didn’t really get character development,” she says.

Prigozy was particularly disappointed with how Long Island fared in the movie, in contrast to its seminal importance in the novel (West Egg was representative of Great Neck/Kings Point; East Egg symbolized Manhasset/Sands Point). In preparing for the production, a studio researcher had consulted her and she emphasized the waters of Manhasset Bay that separated Gatsby from Daisy Buchanan, his obsession. In the final film, Luhrmann didn’t shoot anywhere on the Gold Coast.

For Fitzgerald, “Long Island was the start,” says Prigozy. “Long Island gave him the basic idea.” But inspiration for Gatsby did not come in 1918 when Fitzgerald was stationed at Camp Mills, an encampment near Garden City. He was hoping to be sent to France but the war ended before he could go overseas.

Fitzgerald made a name for himself a few years later in New York as the author of This Side of Paradise, which evoked the restlessness of his generation as the Jazz Age dawned. He was a successful writer, married and a father. The suburbs beckoned.

Back then, Great Neck was a precursor to Hollywood, in part because the Astoria studios were in their glory and the bright lights of Broadway were nearby. The newly minted millionaires mingled with the celebrities from show business such as Sam Goldwyn, Eddie Cantor, Joan Crawford, Paulette Goddard, Charlie Chaplin, W.C. Fields, George M. Cohan, Groucho Marx, and Ed Wynn. Herbert Swope, the editor of the New York World, hosted many parties at his Kings Point estate, which Fitzgerald attended with his neighborhood pal, Ring Lardner, a well-known sportswriter, who lived on East Shore Road with his wife Ellis. In 1925, when The Great Gatsby was published, Lardner had notably written that “Mr. Fitzgerald is a novelist and Mrs. Fitzgerald is a novelty.”

“Kings Point was a very elegant place but it looked across to Sands Point,” says Prigozy, “and Sands Point was the place for society.”

So if Kings Point was for the social climbers, the palatial estates across the bay were for the top rungs of America’s landed aristocracy, where the Pratts, Whitneys, Roosevelts, Fricks, DuPonts, and the Vanderbilts gave the Gold Coast its name.

Fitzgerald and Lardner gazed across the bay and “that’s where they got it,” Prigozy says, “where Fitzgerald got that inspiration.”

At one of Swope’s parties Fitzgerald met Arnold Rothstein, a notorious gambler who had fixed the 1919 World Series (the infamous “Black Sox” scandal). Rothstein, who became a model for Meyer Wolfsheim in the novel, was linked to a Great Neck neighbor of Fitzgerald’s named Edward M. Fuller. With his crooked brokerage firm partner William McGee, Fuller had been convicted of gambling away millions of dollars of their customers’ money. For his portrait of Tom Buchanan, Daisy’s super-rich husband, Fitzgerald drew upon his friendship with the patrician polo star Tommy Hitchcock, whom Fitzgerald saw play championship matches at the Meadow Brook Club in Nassau.

These early influences may explain why Fitzgerald’s first working title for Gatsby was: Among the Ash-Heaps and Millionaires. His astute editor at Scribner’s, Maxwell Perkins, gently persuaded him to think again. After Fitzgerald sent Perkins the manuscript from Paris, he still wanted to tinker around with the title, suggesting Trimalchio in West Egg. Perkins read the finished manuscript in one sitting and told Fitzgerald he thought the novel “splendid.” But that title didn’t cut it, he cabled the author, explaining that nobody would recognize Great Neck nor remember that Trimalchio was the decadent Roman parvenu encouraging debauchery at his banquet in Petronius’ Satyricon. As for “egg,” a family friend, Arnold Turnbull, later wrote that while Fitzgerald was living in Great Neck, his “magic word was ‘egg.’ People he liked were ‘good eggs’…and people he didn’t like were ‘bad eggs’ or ‘unspeakable eggs.’”

Although The Great Gatsby was a critical success but a commercial failure, Fitzgerald remained forever proud of it. In 1930, he wrote Zelda, who was then hospitalized after having a mental breakdown, that he had dragged the novel “out of the pit of my stomach in a time of misery.” More importantly, he had stuck to his vision, refusing to focus on “hauntedness…rejecting in advance…all of the ordinary material for Long Island, big crooks, adultery theme & always starting from the small focal point that impressed me—my own meeting with Arnold Rothstein for instance…”

Fitzgerald lived in Great Neck from 1922 to 1924, but it made an indelible impression. He began The Great Gatsby there and finished it in Paris when he was only 28 years old. Despite his relative youthfulness, he managed to speak for the ages.

“I think it’s a book that’s always going to be relevant because it’s really about our vision of our country as we want it,” says Prigozy. “And we do want to be the country that Fitzgerald also wanted—and that the characters wanted—that somebody could go from nowhere to become somebody.”

But in the end, Gatsby’s true roots lie exposed and he never does escape his past, let alone live in the future he had dreamed of, with the love of his life. And so, using Long Island’s unforgiving but inviting geography—so close yet so far—to depict the great divides of wealth and class, Fitzgerald instills yet one more lesson that the American Dream can only go so far.