There once stood a large elm tree at the corner of Essex and Washington streets in Boston responsible for sparking and embodying the patriotic spirit that fueled the American Revolution. In 1765, patriots such as the Loyal Nine and Sons of Liberty hung in effigy the official charged with implementing that year’s infamous Stamp Act—which among other stipulations required magazines and newspapers to be printed on British paper; viewed as a form of censorship among colonists. The protest was the first public act of defiance against the British government and transformed the tree into a rallying point for the growing resistance simmering throughout the 13 colonies. Soon, a sign proclaiming “Tree of Liberty” was affixed to its trunk. This spirit did not fade when British troops tarred and feathered dissenters beneath its branches, nor after it was cut down during the siege of the city. Rather, “Liberty Trees” sprang up across the fledgling confederation and inspired even more to speak out and oppose the assault on colonists’ civil liberties, rights they believed were theirs. The tree became a flashpoint for revolution, and its image emblazoned many “traitors” and “rebels” struggling to be free from oppressive rule who sought to establish a government reflective and representative of its people’s best values and interests…

“The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure,” wrote Thomas Jefferson soon after the signing of the U.S. Constitution.

Namir Noor-Eldeen walks through the bright sunlight of an open courtyard in New Baghdad, Iraq, his camera slung around his shoulder, the same he’s done countless times before as a photojournalist for Reuters covering the ensuing chaos of the U.S.-led invasion.

The 22-year-old, one of the most well-respected war photographers in the industry, is once again accompanied by 40-year-old Reuters camera assistant and driver Saeed Chmagh; two of about a dozen or so men talking and strolling casually to the right of a nondescript building in the eastern suburb of the capital.

“Okay we got a target fifteen coming at you,” crackles a voice from the cockpit of an AH-64 Apache gunship hovering about a mile away, the crosshairs of its 30mm machineguns bouncing from the dome of a nearby mosque to the torsos of the group, before focusing for a time on Chmagh, then Noor-Eldeen. “It’s a guy with a weapon.”

Their sights zoom in as the men continue through the yard; several others standing beside a scooter while others occupy a nearby street corner.

“Stay firm,” commands another voice over the radio. “And open the courtyard.”

“Yeah roger,” a voice responds. “I just estimate there’s probably about 20 of them.”

The vantage zooms in closer, the crosshairs settling on Chmagh for a few moments, who appears to be carrying a satchel, then back to Noor-Eldeen.

“That’s a weapon,” states a voice.

“Yeah,” another agrees.

“Fucking prick,” blurts a voice, the crosshairs focusing on Noor-Eldeen’s crotch.

“Have individuals with weapons,” says another as the gunship banks to the left, the men falling out of view behind a building.

“Hotel Two-Six, Crazy Horse One-Eight,” spits the radio. “Have five to six individuals with AK-47s. Request permission to engage.”

“Roger that,” another responds. “We have no personnel east of our position. So, uh, you are free to engage, over.”

“I’m gonna—I can’t get ’em now because they’re behind that building,” says a gunner. “He’s got an RPG!”

“All right, we got a guy with an RPG,” says another.

“I’m going to fire.”

“Okay.”

“Hotel Two-Six, have eyes on individual with RPG,” says a voice. “Getting ready to fire. We won’t—“

“Yeah, we got a guy shooting,” interrupts another.

“God damn it,” says a voice, the camera’s view shifting to the building’s right flank. As the gunship turns the corner, its crosshairs align with one of the men in the group, who’s looking in the opposite direction.

“Just freakin’—once you get on ‘em, just open ‘em up,” declares a voice.

“You’re clear,” says a voice.

“All right, firing,” responds another.

“Let me know when you’ve got them.”

The crosshairs target the center of about 10 people huddled together, most of their backs to the gunship.

“Let’s shoot,” says a voice.

“Light ’em all up,” says another.

“Come on, fire!” someone shouts.

Bodies drop as a barrage of shelling shreds the crowd.

“Keep shootin’, keep shootin’,” a calm voice states.

Dirt and debris are launched into the air as the earth explodes from beneath the men and machineguns rattle and hiss.

“Keep shootin’,” the voice repeats.

The crosshairs dance within the dust, tracking any distinguishable human form and a thick cloud billows upward, blocking the view. More bursts of gunfire, more smoke.

“Come on, fire!” shouts a voice.

“Yeah, we see two birds and we’re still fir[ing],” says another.

“I got ’em…,” says a voice before another cuts in.

“All right,” he laughs. “I hit ’em.”

The laughter continues with the sights fixed on the massacre.

“All right, you’re clear,” someone says.

“All right, I’m just trying to find targets again,” assures the shooter.

As the smoke clears the lifeless men are strewn across the courtyard, many distorted into odd shapes and mutilated; some lying bent and twisted atop each other.

“Got a bunch of bodies layin’ there,” says the shooter.

“All right, we got about, uh, eight individuals,” says another.

“Yeah, we got one guy crawling down there,” someone adds. “We’re shooting some more.”

“Hey, you shoot, I’ll talk,” a voice responds.

“Currently engaging approximately eight individuals, uh KIA, uh RPGs and AK-47s,” radios another.

The camera again scans the yard. Piled, mangled bodies, some staining the ground, become clearer.

“Oh yeah, look at all those dead bastards,” says the gunner.

“Nice,” says another. “Nice. Good shootin’.”

“Thank you.”

The crosshairs circle back to Chmagh, lying crooked halfway on the curb and street, his left leg twisted unnaturally 180 degrees off alignment, the back of his head and shoulders jilting upward as he struggles and pushes off his elbows.

“He’s getting up,” says a voice.

“Maybe he has a weapon down in his hand?” asks another.

“No, I haven’t seen one yet,” says the shooter.

Face down, Chamgh somehow gets to his knees.

“Come on, buddy,” eggs a voice.

“All you gotta do is pick up a weapon,” says another.

The camera zooms in on a dark van that pulls up alongside Chamgh. Two men begin trying to lift him up by his arms and legs.

“We have individuals going to the scene, looks like possibly picking up bodies and weapons,” someone says.

“Let me engage!” shouts the gunner. “Can I shoot?”

“Come on, let us shoot! They’re taking him.”

“Fuck,” says a voice as the men try and load him into the van.

“Roger,” says another. “Engage.”

“Come on!” shouts the gunner to the rattling of more machinegun fire. The van shakes violently as its front explodes, bursts of light flashing from its inside before jolting forward several feet and slamming backwards and to the side, smoke and shrapnel again clouding the scene.

The gun jams briefly before resuming; after a few moments the smoke clearing. A basketball-sized hole is seen through the center of the windshield. The men who were helping Chamgh lie motionless and outstretched around the van.

“Oh yeah, look at that!” laughs the gunman. “Right through the windshield.”

“I think we whacked ‘em all,” someone adds.

“That’s good,” says another.

“Hey yeah, roger, be advised, there were some guys popping out with AKs behind that dirt pile break,” a voice informs an incoming ground team that will be photographing the scene. “We also took some RPGs off, earlier, so just make sure your men keep your eyes open.”

Instead of armed insurgents, the team discovers two severely wounded children in the van; its driver, their deceased father, had been driving them to school when he saw Chamgh and attempted to bring him to a hospital.

“Well it’s their fault for bringing kids into battle,” says the gunner, following up a comment about how a tank crushed a body as it approached.

The massacre and cockpit chatter among the two U.S. Apache helicopters participating in it make up the bulk of Collateral Murder, leaked classified cockpit gunsight footage of July 12, 2007 airstrikes that killed, along with all of the other men accompanying them, Reuters journalists Noor-Eldeen and Chmagh. Following their deaths the media organization requested the footage documenting the clash to no avail; Noor-Eldeen’s body reportedly discovered by a friend in a dilapidated Iraqi morgue.

A clearer view of the truth of that tragic day did not emerge until Julian Assange, founder of WikiLeaks—the online international nonprofit whistleblower site which publishes secret, classified and leaked news material about governments and corporations from around the world—presented the footage on April 5, 2010 at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. and made it available to the world via wikileaks.org and collateralmurder.com.

The U.S. military characterizes the slayings as justified. Subsequent military reports released the same day as Collateral Murder hit the Internet state the journalists were not wearing anything that would identify them as such, their Canon EOSs with telescopic lenses resembled weapons, and they were among armed insurgents; the military says weapons were found by ground troops at the scene.

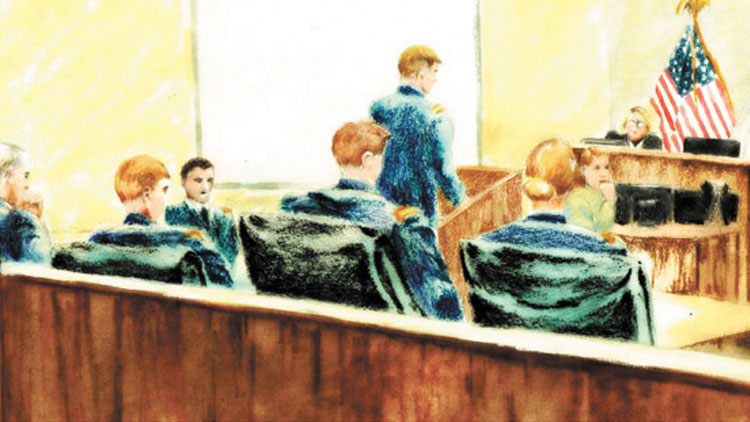

In February, U.S. Army Pfc. Bradley Manning, who’s currently facing a military court martial at Fort George G. Meade, Maryland for leaking more than 250,000 U.S. diplomatic cables and more than 490,000 classified U.S. Army reports from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, pleaded guilty to 10 of the 22 charges against him, including sharing the aforementioned video. The 25-year-old faces life in prison if convicted on the heftiest charges under the Espionage Act of 1917 and aiding the enemy.

Listen to Manning’s statement:

Yet this is not your typical court martial, contend the few core journalists who’ve been covering Manning’s plight since the beginning—he was arrested in May 2010 after an informant turning over chat logs to the FBI—other whistleblowers, advocates and outside observers. Nor is Manning, who’s been jailed for more than three years, sometimes in solitary confinement and in conditions so severe it caused international uproar and State Department spokesman Philip J. Crowley to resign in protest, your typical soldier.

Taken within the larger context of 2001’s Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF); alarming new provisions of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) and Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA); a recent power grab by the military sans Congress the Long Island Press exposed in May which essentially suspends the Posse Comitatus Act and allows the military to take authority over undefined “domestic disturbances”; the government’s recent admission it seized the phone records of the Associated Press and a reporter as part of an investigation into an alleged leak; the naming of Fox News reporter James Rosen as a co-conspirator in another investigation; and the Pandora’s box the latest U.S. government whistleblower, former National Security Agency (NSA) contractor Edward Snowden leaked to The Guardian’s Glenn Greenwald about the government’s ongoing mass surveillance programs; Manning’s prosecution has ramifications on the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. It has ramifications on the Fourth Amendment. It speaks to a larger discussion regarding the lack of whistleblower protections, especially for those employed in the national security and intelligence sectors—President Barack Obama has used the Espionage Act more than double all presidents combined. It shines a light into the murky back-alley dealings of U.S. foreign policy, opening the door for more rigorous debate about the ever-growing U.S. military industrial complex and covert surveillance forces. And it has tremendously significant ramifications for the future of journalism—specifically investigative journalism.

That is because Manning’s trial is also very much a trial about WikiLeaks, which the U.S. government is widely believed to have empanelled a grand jury against and which the judge, Army Col. Denise Lind ruled in pre-trial hearings, has the same standing as a media outlet as The New York Times and Washington Post, who also published significant portions of he and Snowden’s classified disclosures.

“What the mainstream media here in the U.S. should realize is: as goes Wikileaks, as goes the mainstream media,” warns Kathleen McClellan, national security and human rights counsel for nonprofit whistleblower advocacy group Government Accountability Project (GAP), at its D.C. headquarters. “There’s no distinction in the law between an organization like WikiLeaks disclosing information and The New York Times disclosing information. The law doesn’t protect either more or less.”

Yet despite what’s at stake, the vast majority of mainstream journalists and news organizations throughout the country have been providing little, if any, coverage of the Manning trial at all (Times Public Editor Margaret Sullivan recently chastised the staff because of it). A handful of dedicated, if lesser-known journalists and outlets have, however, and theirs has been the most in-depth and consistent reporting on the proceedings to date—to where many others frequently call seeking input before publishing their own stories. Sometimes, they’ve been the only coverage.

Their commitment has oftentimes come at great costs and sacrifices.

WHO WOULD YOU SAY IS REVOLUTIONARY?

CLICK HERE AND TELL US IN THE COMMENTS

DIRTY WARS

The Obama administration’s harsh treatment and prosecution of Manning and the shadowy actions of military and covert surveillance operations both overseas and domestically are not new occurrences, rather, the war between the government and public over what information is shared and what stays secret has been raging since the birth of the country, with revealing glimpses behind the curtain every so often.

Independent investigative journalist-turned-Pulitzer Prize winner Seymour Hersh exposed what has become known as the My Lai Massacre—the mass murder and cover-up of up to more than 500 unarmed South Vietnamese villagers, including women and children, by U.S. Army troops in 1968. Initially it was reported to the public that 128 enemy combatants were slain in battle.

Daniel Ellsberg leaked a classified internal Department of Defense report detailing much of the decision-making behind U.S. policy and involvement during the Vietnam War in 1971 and was also tried under the Espionage Act, yet the judge ruled a mistrial after learning about, among other actions taken against him by the intelligence community, the tapping of his phones.

The Watergate break-in, orchestrated by President Richard Nixon’s CIA-connected “plumbers” and exposed by Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein with help from perhaps the most infamous whistleblower in U.S. history, former top FBI official Mark Felt, aka Deep Throat—also ironically essentially a case of presidentially condoned domestic spying, albeit on the National Democratic Committee headquarters instead of the general public at large—resulted in an investigation by the Senate and culminated in Nixon’s 1974 resignation.

The following year’s Senate Select Committee to Study Government Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, known as the Church Committee after Democratic Sen. Frank Church of Idaho, stands as perhaps the most intrinsic look inside the inner workings of this world to date. It probed not only the CIA’s activities for illegalities and abuses, but the NSA and FBI—including the agencies’ roles in assassinations targeting foreign leaders.

Among the findings: The CIA had varying roles in coups and assassination plots in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Dominican Republic, Chile, Cuba and Vietnam. In the case of the Congo, the committee discovered the agency had plotted to kill its newly elected Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, and although didn’t ultimately do the deed (the Belgians did), had supplied weapons and money to help it along, originally planning to poison the leader.

The committee also shed light on just how high up the chain of command these orders came, revealing a concept called “plausible deniability,” meaning the president and other officials with authority to pull the trigger on such activities could know without knowing about them and escape blame.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower was implicated in the Lumumba takedown, according to the committee’s reports. Classified information detailing the government’s roles in similar schemes in Iran and other countries wouldn’t surface until decades later.

The Church Committee also discovered widespread domestic surveillance operations by the CIA, including the mass photographing and/or opening and resealing of citizens’ mail without even the U.S. Postal Service’s knowledge.

In 1996 Pulitzer Prize investigative journalist Gary Webb exposed the CIA’s involvement in at least permitting Nicaraguan drug smugglers linked to the Contras to peddle crack cocaine on the streets of Los Angeles in the 1980s as a way to fund its guerrilla operations during the Reagan administration.

Jeremy Scahill, reporter for The Nation, exposes questionable present-day operations in the recently published Dirty Wars: The World Is A Battlefield, also a documentary in theaters now. Besides uncovering the self-authorized international assassination program of the CIA’s Special Activities Division and the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC)—according to Scahill, the equivalent of the president’s personal death squads with international reach, though Americans can also be targeted—he documents the systemic eradication of nearly all oversight over such forces, arguing, that their actions actually serve to perpetually feed the “War on Terror.”

Sept. 11, 2001 opened the door.

“To fight its global war,” writes Scahill, “the White House made extensive use of the tactics [former Vice President Dick] Cheney had long advocated. Central to its ‘dark side’ campaign would be the use of presidential findings [executive directives] that, by their nature, would greatly limit any effective congressional oversight.

“According to the National Security Act of 1947, the president is required to issue a finding before undertaking a covert action,” he continues. “The law states that the action must comply with U.S. law and the Constitution. The presidential findings signed by [President George W.] Bush on Sept. 17, 2001, was used to create a highly classified, secret program code-named Greystone. GST, as it was referred to in internal documents, would be an umbrella under which many of the most clandestine and legally questionable activities would be authorized and conducted in the early days of the Global War on Terror.

“It relied on the administration’s interpretation of the AUMF passed by Congress, which declared any al Qaeda suspect anywhere in the world a legitimate target,” he adds. “In effect, the presidential finding declared all covert actions to be preauthorized and legal, which critics said violated the spirit of the National Security Act. Under GTS, a series of compartmentalized programs were created that, together, effectively formed a global assassination and kidnap operation.”

In other words, where in the past journalists including Hersh were rewarded for exposing war crimes and corruption, the government’s espionage case against whistleblower Ellsberg was dropped and the president of the United States ousted due to disclosures about covert surveillance, nowadays, an Army private and former NSA contractor face decades, if not life in prison for exposing the same crimes, news outlets such as the AP have had their phone records seized and a journalist has been named as a co-conspirator in the government’s attempt to plug a leak.

All indicative, say critics, of an ongoing war not just against journalists, but civil liberties across the board.

“Gone are the days of Watergate and the Pentagon Papers,” laments Jane Hamsher, founder and publisher of FireDogLake.com, a progressive news site and action organization that’s been covering Manning’s story and trial for years. “You got the government considering whistleblowers terrorists and journalists looking down their noses on people who are sources.”

“What we’re really seeing here is a war on information and who controls information,” says GAP’s McClellan. “Cracking down on what the public is going to hear and cracking down on who can speak to certain issues.”

“It’s so hard on the whistleblowers,” adds Hamsher. “It’s just so emotionally hard on them. They’re destroyed, they’re wiped out financially, they’re called traitors, they lose their jobs. Anybody who thinks this is something somebody does for attention is out of their minds.”

She would know. FireDogLake’s headquarters—a two-story house in Northwest D.C. (ironically a few blocks from Manning Place)—not only serves as its staff’s newsroom and lodging, but doubles as a meeting/refuge space for whistleblowers and others who’ve risked a lot in order to broadcast the truth.

WHO WOULD YOU SAY IS REVOLUTIONARY?

CLICK HERE AND TELL US IN THE COMMENTS

BLACKOUT

They travel from other states every week, put their personal lives on hold, sleep wherever they can—local hotels, rented rooms or the homes of those sympathetic to the mission: telling the story of Bradley Manning and his trial, raising awareness about the case and its larger context, documenting history. They wake up at the crack of dawn and they make the trek to Fort Meade, Md.

At least once a week they’ll pass a crowd of people of varying numbers protesting on their way in. They stand outside the base’s main gates, sometimes holding signs, often wearing black T-shirts proclaiming “TRUTH” in white block lettering—the weekly vigil of supporters and Bradley Manning Support Network members. Some have come from across the country; some have come from other countries entirely.

The journalists wait in their vehicles till around 8 a.m. or whenever the MPs show up to inspect their paperwork, credentials, vehicle registration, photo identification and vehicles. They’re eventually escorted to the other side of the complex to a small hall serving as the “media operations center.” Journalists can also opt for a limited number of seats in the courtroom.

Here, the proceedings are broadcast from one wall-size projector screen and journalists are permitted to bring along a computer “for filing and note taking purposes only.” Filing is to be done when court recesses. Social media posting may only be done when court is in recess or during break.

Seventy journalists can fit here and more than 250 applied for opening arguments, but since then there’ve only been about a dozen on average. Half as many have been here consistently.

The live feed from the courtroom occasionally craps out in the middle of important testimony [as it did on June 26, prompting complaints], and the shotgun speed the judge issues rulings and prosecution reads critical testimony into the record are regular sources of familiar jokes and frustration. More frustration, however, since unlike a traditional court proceeding, there is no official transcript provided for the public, and thus, no public record of what is said during the proceedings unless these handful of journalists write it all down, as fast as they can.

“I often times get asked, ‘Why do you do this?’” says Alexa O’Brien, one of them, who’s been covering Bradley Manning for three years and is single-handedly responsible for transcribing and posting on her website AlexaOBrien.com literally every single syllable and filing she could type or obtain, including from the pre-trial hearings. She’s also recently built an online, searchable database for this. “I don’t have a simple answer for it.”

“It’s the largest leak trial in U.S. history,” she explains in the empty media parking lot following June 26’s proceedings. “It has ramifications, wide ramifications, on the First Amendment and foundational purposes of our government and of society at large.

“The government is using charges in this court martial that have never been used in military law,” continues O’Brien. “They want to take the intent and the motive out of the Espionage Act, and that intent makes the Espionage Act as constitutional as it could possibly be. It’s a First Amendment right.

“The Department of State has been the puppet master in this prosecution vis-à-vis this—the largest criminal investigation ever into a publisher, which is the U.S. investigation into WikiLeaks—and we don’t see in any of the major papers the kind of reporting about what is happening…and what is at stake,” she adds.

Kevin Gosztola, reporter for FireDogLake.com, seated in the backyard of its headquarters, agrees. He, along with O’Brien, the Associated Press’ David Dishneau, Adam Klasfeld from Courthouse News Service, a news wire, and Nathan Fuller of the Bradley Manning Support Network, make up the core of stalwarts covering the case.

“When you think about what happened,” says Gosztola, “the significance isn’t just the act itself but the disclosures, the content of what was released to WikiLeaks—when you look at the Collateral Murder video and what it revealed, the killing of Reuters employees who were out there basically doing their news jobs, and the fact that somebody wounded was killed and shot and you can hear the bloodlust in the voices of the soldiers who seem to be playing some kind of video games—and when you look at the U.S. diplomatic cables and the different military reports from Iraq and Afghanistan that he disclosed, which give a full, complete picture of those wars, a picture vastly different than the one the United States government was promoting to people during the war, I think that’s some of the importance and significance of his act, in that he punctured a hole in this whole secrecy that we have in our government and gave us a way to tell a lot of information that probably shouldn’t have ever been kept secret from us in the first place.”

Two tremendously large poodles gallop by as Hamsher explains FireDogLake’s purpose and origins inside.

“This is what is called the Hamsher Hotel,” she smiles, while chopping mixed vegetables on the kitchen counter into a salad. “Glenn Greenwald’s room is upstairs; Kevin is staying in it now. Glenn has his own room. Dan Ellsberg stays there. Dan Choi stays there. We have dinners here like once a month or so with [NSA whistleblower] Tom Drake and [CIA torture whistleblower John] Kiriakou before he went to jail—Peter Van Buren, all the whistleblowers. We really try and have a place that nurtures and takes care of people.”

“I was just interested around the time of the 2004 Election and the power of online media and what it could do, and I was posting on Daily Kos and whenever I would finish I would post it on a free blogspot that I called firedoglake because I like to lie by the fire and watch the Lakers with my dogs,” she says. “And we started writing about the Scooter Libby trial and the next think you knew we had 100,000 people a day showing up. So it expanded to more than just me writing and now what Kevin does is very much in the tradition of what we started with, which is providing a counter-narrative to stories that aren’t being adequately covered or that are sort of overwhelmed by propaganda distributed by powerful self-interested people.”

“They’re seeking life in prison for giving secret documents to a news organization and so that would essentially turn whistleblowing something akin to treason and that’s already had a huge chilling effect on sources for investigative journalists,” says Fuller, from the support network’s home base, a rented house in Columbia, Md.

Fuller says he’s “talked to reporters who have been to Guantanamo Bay for military tribunals, and they say this is the more restrictive case,” adding that the judge has been clocked reading one of her rulings at 100 words per minute.

Klasfeld, standing on a dock in the shadow of the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, stresses the importance of keeping the focus on the content of Manning’s disclosures.

“I think one thing that needs a little more emphasizing and highlighting is: Just what exactly did Bradley Manning leak?” he asks. “What do we know now in 2013 that we didn’t know before WikiLeaks published all this information in 2009 and what is the value of that information? What do we know about what’s going on in Guantanamo Bay? What do we know about what happened in the Iraq and Afghanistan War? Whether it comes to casualty counts or incidents that weren’t investigated, what did we not know about the conduct of U.S. diplomacy that we do know now?

“In a lot of the focus in who Bradley Manning is and what WikiLeaks is, the personal drama of it—which is interesting—just what was leaked has gotten the short shrift.”

It’s that content, along with a host of varying personal reasons, which attracts Manning supporters from across the globe to Ft. Meade—a trek that also requires an ample amount of dedication from the members of the public who do.

WHO WOULD YOU SAY IS REVOLUTIONARY?

CLICK HERE AND TELL US IN THE COMMENTS

SECRET COURT

It’s approaching 9 a.m. and nearing 90 degrees by the time a soldier wearing U.S. Army fatigues walks over to the makeshift barricade in a back parking somewhere in the 95-acre complex of Ft. Meade to tell Dominic and Cynthia Vautier of Bellevue, Wa. that the start of the trial is going to be pushed back a bit.

There are no signs indicating this is the courthouse, and nowhere to find reprieve from the sun. Were it not for the makeshift fencing—long lines of bicycle racks stacked alongside each other and a printout that warns not to go beyond the barricade—a visitor might imagine they were at one of the dozens of other military facilities throughout the base.

The 71-year-old software engineer and Vietnam-era veteran sits on the hot cement, legs crossed, while his wife, 64, gazes behind the line at several air-conditioned trailers housing soldiers when David Reed, another spectator, joins them. He jokes that maybe they’re not letting Dominic in because he looks suspicious.

“I would have thought there would be more people coming to the trial,” the 67-year-old retiree says. “It’s an apathy.”

“It took us two days to figure out how to get into the fort,” says Dominic, explaining that the couple made the trek as part of Cynthia’s vacation.

“When I’m a grandmother, I feel that I should be able to tell my grandchildren with great pride that I was at this trial and supported a hero,” she says.

Soon others join them, many wearing “TRUTH” shirts. In all, about 50 supporters wait in the heat till they empty their pockets, are scanned with a magnetometer, obtain a pass, wait for a while in a side room and finally enter the courtroom (25 are permitted, the rest head to an overflow trailer).

Kat, 47, from Ontario, who wore a “TRUTH” shirt and declined to give her last name, stressed the importance of being there to “show my support and be a witness to the proceedings and make it less secretive,” she says. “We’re here in support of Bradley and for people telling the truth, for example, Bradley Manning—about war crimes.”

Deb Van Poolen, an organic farmer and artist-turned-court sketch artist who’s been coming to the trial every day to capture the scene and making them available on her website for free to raise awareness, takes a seat in the first row, behind the prosecution team.

Two plainclothes soldiers, one with an earpiece, a sidearm and a taser, stand arms crossed between the public and Manning, who is dwarfed by his lead attorney David Coombs, Major Thomas Hurley and Captain Joshua Tooman.

Three empty rows of 12 empty chairs and computers fill the courtroom to the right of the judge; five cameras pointed at the public are mounted above her head. Each session begins with a decorated Army official reading aloud a list of rules, which includes no loud whispering and no falling asleep.

When U.S. Army prosecutor Major Ashden Fein isn’t standing before the judge, he slouches back in his chair while two other prosecutors occasionally giggle with each other. Manning and his team sit upright, intently listening to every utterance. Between two recesses the visitors dwindle to about 15; by 3 p.m. there is an hour-long closed session. Judge Col. Lind informs the trial will resume the following day at noon.

It’s now that the media center crew hurries to file their stories and post them on their websites, Tweet out updates and prepare for the next day.

“I knew the trial was going to be conducted in secrecy and de facto-secrecy and I felt that there was no coverage of it that was satisfying to me, gave me the information, answered any of the questions that I wanted to have answered, and so I decided that I was going to transcribe it,” O’Brien tells us back in the empty media parking lot. “I think if Manning gets sentenced to life, that is going to be a historic day in the history of our country, but I think also, just civilization in general.”

“I do believe that fundamentally, it is our responsibility if we do know better, to do everything we can to dissent, but also to do the right thing here,” adds O’Brien. “The act of doing a transcript, for example, is a very simple act, but if it’s going to get me almost arrested at Ft. Meade, if it’s going to get me in a situation where I am somehow counter, there’s something wrong there.”