In the opening minutes of Kristina Borjesson’s devastating new documentary on the fate of TWA Flight 800, one of the eyewitnesses who saw the crash unfold points to the horizon and tells the camera, “All of a sudden I see something rise up from those trees over there!”

As many Long Islanders will never forget, the sun had barely set that perfect July day and the twilight sky was clear. The jet airliner had just taken off from JFK International Airport with 230 people on board headed for Paris when it suddenly exploded 10 miles off East Moriches.

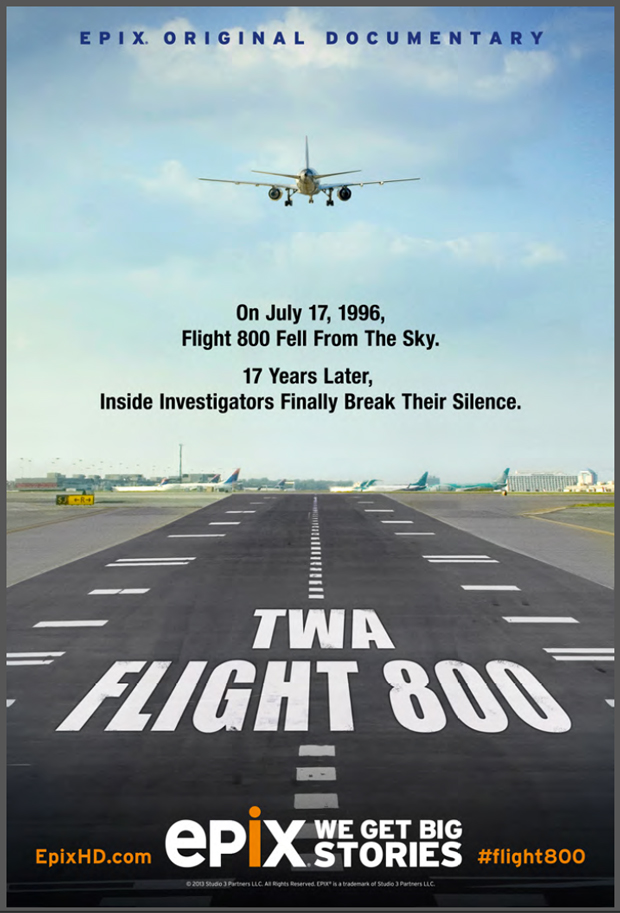

Now, on the 17th anniversary of the July 17, 1996 tragedy, one of America’s most controversial aviation investigations takes the spotlight at the Stony Brook Film Festival.

“With the festival being less than 20 miles from the memorial site [on Fire Island at Smith Point], I felt we were the perfect venue for this film,” says Alan Inkles, founder and director of the film festival now in its 18th year. He saw an early version of TWA Flight 800 in the spring, calling it both personal and universal at the same time. “I was extremely taken by both the subject matter and its exceptional work as a film,” he says.

“We feel that this is very much a Long Island story,” says Borjesson, an Emmy Award-winning journalist, who wrote, directed and co-produced the film. “There are a lot of eyewitnesses who live on Long Island, and we felt it was appropriate to have a screening where everybody there could see it, and it would get attention.”

As she tells the Long Island Press, almost a hundred people, all unrelated and in different locations along the South Shore, saw the entire incident, from the moment streaks of light shot from the surface and intersected the jetliner to when the plane burst into a fireball and plummeted into the Atlantic Ocean.

The government’s official explanation is that one of the fuel tanks onboard caught fire when an electrical wire supposedly short-circuited. But as six former members of the investigation’s team who finally broke their silence to appear in public reveal in this emotionally riveting film, that explanation just doesn’t fly—and they hope it never will again.

This documentary premieres July 17 on the EPIX cable network, a joint venture of Viacom, MGM and Lionsgate, available through Verizon FiOS and the DISH Network. It will get its Festival premiere screening on July 20 at 3 p.m., followed by a panel discussion with Borjesson and Tom Stalcup, a physicist in Massachusetts who devoted his life to unlocking the truth about what happened after seeing an animation of the crash that the CIA had produced which he found unscientific and unbelievable. Jeff Sagansky, a former president of CBS Broadcasting, where Borjesson once worked, is executive producer.

“This is the first documentary on TWA Flight 800 that deals strictly with firsthand sources, people who handled the evidence, with the exception of Tom,” she says. Among the key members of the original investigation team who came forward to speak in this documentary are Hank Hughes, senior accident investigator for TWA now retired; Bob Young, chief accident investigator for TWA now retired; and James Speer, the Air Line Pilot Association’s representative/investigator, also retired. “They’re experts and they know what they’re talking about,” Borjesson says.

EVIDENCE TAMPERING

As reports of this documentary’s forensic assertions started to trickle out to the media in the weeks leading up to the premiere, James Kallstrom, the retired head of the FBI’s New York office, and others have started pushing back, hard.

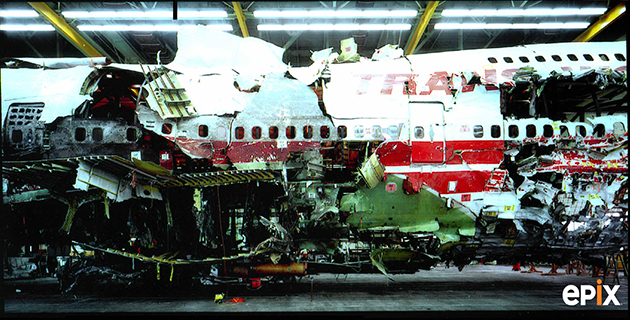

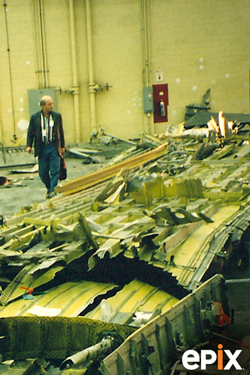

Kallstrom had become the public face of the 1996 inquiry once the FBI declared it a “criminal investigation” and took it over from the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), which routinely handles domestic aviation accidents. In the documentary, the civilian investigators say they found holes in parts of the fuselage that FBI agents wouldn’t let them photograph as well as traces of nitrates on parts of the plane that the bureau wouldn’t let them test independently. They reported agents were hammering parts of the plane flat and changing evidence tags on debris. Just as tellingly, Speer found that an underwater video taken of the recovery effort was expurgated and he was rebuffed when he asked to see the original version, which would have helped investigators reconstruct the timeline of the crash.

Now back in the media glare, Kallstrom has tried a multi-pronged approach. He said the evidence cited in the documentary was recycled and discredited—a false claim as the documentary makes unmistakably clear—and he questioned the investigators’ motives.

“If they were so committed…why did they wait until they retired?” he asked news outlets.

“They didn’t wait,” counters Borjesson adamantly. “They spoke up. And Jim Speer…almost got himself kicked off the investigation twice…. After TWA Flight 800, Hank was relegated to [investigating] minor accidents. He was punished for what he did. Kallstrom doesn’t mention that!”

Ironically, the night of the crash, Borjesson, whose husband is French, had gone to bed early after sending her 11-year-old son off on an Air France flight to Paris to see his relatives. She’d just finished wrapping up a show for CBS Reports on Fidel Castro and went home exhausted.

She was woken up out of a deep sleep by a phone call at 9 p.m.

“My neighbor says, ‘Was that your son’s plane that just went down?’” Borjesson recalls. “And for a minute, I felt what those victims’ family members were feeling. I will never forget that feeling.”

Her son’s plane had departed five minutes behind Flight 800. The next day when she went to work, she was assigned to cover the TWA crash, launching her on the long, turbulent journey that will bring her to Stony Brook later this month to reveal what her years of investigative journalism have found.

Once the FBI took over the inquiry, they wouldn’t let the NTSB investigators interview the eyewitnesses as they normally would have in a typical airline crash follow-up. And the media, from the New York Times to NBC News, swallowed what officials were pushing: that the witnesses “were not credible.”

“You have high-ranking sources [in the government] giving you the inside scoop,” Borjesson says of her former colleagues in the Fourth Estate. “But the inside scoop is bullet points of their agenda…. All these high-level people are just telling you what they want you to think because they already have an outcome in mind.”

For her film, which cost about $500,000 to make, Borjesson wanted to question William Perry, who was Secretary of Defense in 1996, because “we think the Secretary of Defense has knowledge that is pertinent to this event.” He declined to participate, as did the man who appointed him to the post, President Bill Clinton.

Over the years some people have speculated that what the witnesses saw were missiles possibly fired by Navy vessels. The documentary will not go there.

Borjesson said her collaborator, Tom Stalcup, “doesn’t want to go one millimeter further than the evidence, the math and the facts will take him.”

And that’s why she would not use the word “missile” in her documentary.

“We call them ‘objects’ for a reason,” Borjesson says. “We want the official investigation reopened so they can be identified.”

With that goal in mind, the investigators cited in the film have filed a petition for reconsideration with the NTSB, as well as another lawsuit against the CIA. Stalcup had obtained heavily redacted documents from the CIA in his lawsuit filed several years ago, which shows CIA analysts taking the eyewitness reports and apparently concocting a scenario to explain that hundreds of people on Long Island did not see what they said they saw.

Now everyone can judge for themselves—something the NTSB may be dreading.

The Stony Brook Film Festival will show a mix of new independent features, documentaries and short films at the Staller Center from July 18 to July 27. Besides TWA Flight 800, other domestic and foreign films will be premiered and indie filmmaker Christine Vachon, whose feature Boys Don’t Cry won an Academy Award for actress Hilary Swank, will be presented with a career achievement award. Vachon has recently joined the Stony Brook Southampton Arts faculty. For more info, call 631-632-2787 or visit www.stonybrookfilmfestival.com.