There is a scene in The Godfather Part II when the Hyman Roth character, played by Lee Strasberg, admonishes Al Pacino’s Michael Corleone over the death of the character credited with building Las Vegas out of a “desert stopover for GIs.”

Roth fixes his steely gaze angrily on Corleone and says, “That kid’s name was Moe Greene and the city he invented was Las Vegas. And there isn’t even a plaque or a signpost or a statue of him in that town.”

The same could be said of Thomas Jasper, the architect of the biggest gambling venture ever invented: the swaps market.

In her book The Futures, Forbes writer Emily Lambert describes how in 1981 Salomon Brothers “pulled an investment banker named Thomas Jasper out of a cloistered office and set him up on Salomon’s trading floor with its loud, swearing, cigar-smoking men.” Jasper’s job was to figure out how to turn a new type of banking agreement called an interest rate “swap” into a contract that could be traded on an exchange much like a commodity. By 1987 Salomon’s new product was ready for market, and as Lambert notes, “by that spring, there were $35 billion worth of bond futures contracts open at the Chicago Board of Trade, and there were $1 trillion worth of outstanding swaps transactions.”

For Wall Street this was like graduating instantly from slots to craps.

Twenty years later, unregulated swaps would be at the heart of the global financial meltdown and the very banks responsible for creating them would be considered “too big to fail.” A lethal mixture of deregulation, manipulation and greed would transform swaps—a type of investment known as a “derivative” in which two parties exchange risk with one another in a negotiated agreement—into opaque mega investments that many traded but few understood.

Today, the global derivatives market is estimated to be somewhere around $1.2 quadrillion—more than 14 times larger than the world economy.

After the crash in 2008, the whole world became acquainted with these investments and some of the toxic assets they were based on. Yet since the crash, and despite the best attempts on the part of regulators to get their arms around the world of derivatives, surprisingly little has changed in the way they are packaged, sold and regulated.

By staying one step ahead of regulators, banks have continued to rake in historic profits. Bart Chilton, a commissioner at the Commodity Futures and Trading Commission (CFTC), is one of the U.S. regulators charged with implementing rules that would curb risky speculative behavior on the part of banks and protect American consumers. He expressed his irritation in an interview with the Press, saying, “The financial sector has made more profits every single quarter since the last quarter of 2008 than any sector of the economy by like a hundred billion dollars. So they crash the economy and still make more than anyone else.”

Chilton points to the aggressive bank lobby against regulators as one major impediment to reform.

“They have fuel-injected litigation against regulators,” he laments. “There are ten financial sector lobbyists for every single member of the House and Senate.”

Despite this frustration, Chilton believes in the importance of speculators “in determining what the prices of things are, whether it’s a home mortgage or a gallon of milk.” Instead of squarely blaming the banks, he believes the question “is whether or not government has allowed too much leeway so that the markets have simply become a playground for speculators to roam and romp.”

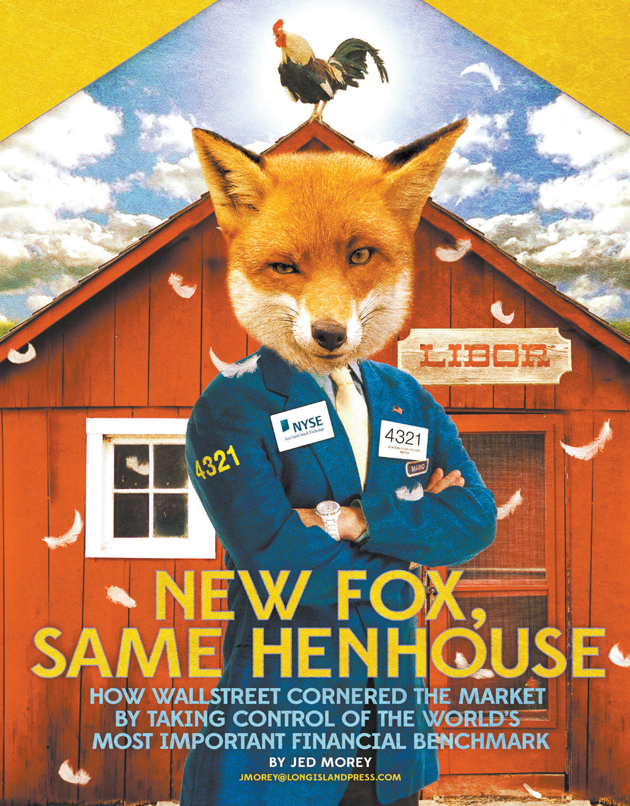

One of the most important determinants in pricing everything from mortgages to the multi-trillion-dollar derivatives market is the London inter-bank offered rate, better known as LIBOR. Barclays, the British banking giant, thrust LIBOR into the headlines last year when it was discovered that it was among a handful of banks found to be manipulating daily rates for its own benefit. The scandal rocked the banking sector and sent European regulators searching for a replacement to LIBOR or, at the very least, a new third-party administrator.

Charting LIBOR’s new path was left to Martin Wheatley, who was head of the Financial Services Authority in the U.K. when the scandal broke. The recommendations, known as the Wheatley Review, included the formation of a panel charged with finding a new host for LIBOR that would restore confidence to the market and ensure transparency in the rate-setting process.

In a twist even Michael Corleone would appreciate, the panel chose Wall Street.

LIBOR: “A huge, hairy, honking deal.”

Beginning in 2008, rumors began to circulate in the financial world that several of the London banks were involved in influencing the daily posted LIBOR rates. During a 2012 House Financial Services Committee investigation into the matter, Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner admitted to hearing the rumors while he served as head of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. In his testimony, Geithner said he attempted to warn U.K. and U.S. regulators but assumed they would “take responsibility for fixing this.”

What the British and American governments knew and when they knew it unfortunately matters little at this juncture, as both have since levied financial penalties on the banks involved that amount to a slap on the wrist. What matters now is how rates are set going forward to ensure some degree of integrity. To understand how the Wheatley Review panel merely chose a new fox to guard the world’s financial henhouse, it’s important to understand how LIBOR is calculated and how much is riding on it.

LIBOR rates are determined on a daily basis. According to an Economist article that details the scandal, “The dollar rate is fixed each day by taking estimates from a panel, currently comprising 18 banks, of what they think they would have to pay to borrow if they needed money.

The top four and bottom four estimates are then discarded, and LIBOR is the average of those left.”

Rates were submitted to the British Bankers Association (BBA), a nonprofit third-party administrator responsible for gathering and posting the data. In theory, the arms-length distance of a disinterested third party provided enough oversight and assurances to the market that rates were being determined fairly. Only the rates weren’t based upon actual market rates. Rather, they were estimates supplied by traders from Europe’s largest banks and therefore surprisingly susceptible to manipulation and, as it turns out, collusion.

Traders were caught periodically manipulating these estimates in order to gain a trading advantage in the market and maximize profit on recent transactions. Moreover, because LIBOR is an indication of the perceived health of a financial institution, bankers had an added incentive to suppress rates to artificially illustrate confidence among their colleagues. In short, everyone was in on it. Because of the global credit crunch, few banks were actually lending large sums to other banks since both sides had cheap and easy access to government dollars to provide market liquidity. This reality made LIBOR even less realistic.

Former Barclays president Bob Diamond initially responded to the scandal by admitting that while manipulation occurred, it didn’t happen “on the majority of days.” The Economist said Diamond’s response was “rather like an adulterer saying that he was faithful on most days.”

Diamond subsequently resigned and so far three U.K. traders, Tom Hayes, Terry Farr and James Gilmour, were swept up in the LIBOR price-fixing scandal. According to the Financial Times, “Mr. Hayes, Mr. Farr and Mr. Gilmour are the only individuals to face U.K. criminal action to date in a global scandal that has seen three banks pay a combined $2.6bn in fines for attempting to manipulate interbank lending rates.”

Many bankers have distanced themselves from the importance of the scandal by calling it a victimless crime. Bart Chilton had a choice expletive for this attitude, and then added, “If it’s a home loan mortgage, or a small business loan or a credit card bill, if you buy an automobile or if you have a student loan, about everything you purchase on credit is impacted by LIBOR. It’s a huge, hairy, honking deal. If somebody says it’s a victimless crime, I bet you it’s a banker.”

Michael Greenberger, a professor at the University of Maryland, has been an outspoken critic of the way derivatives have been regulated for several years. (The Press first spoke with Greenberger for a 2008 cover story on the price manipulation of crude oil.) He weighed in on the Obama Administration’s reaction to the LIBOR price-fixing scandal saying, “This Justice Department is settling these LIBOR cases for what you and I would consider to be traffic tickets.”

Considering who is about to be in charge of administering LIBOR, the Obama Administration and U.S. regulators might want to pay close attention to how the process unfolds.

The Wheatley Review panel chose NYSE Euronext to step into the BBA’s role as administrator of LIBOR. On the surface, choosing the members of the New York Stock Exchange—one of the oldest and most trusted brand names in global finance—to oversee rate-setting seems like sound concept. Only the NYSE isn’t the clubby, self-governed body of individual members it once was. Today the exchange is a publicly traded, for-profit business whose shareholders include none other than the world’s biggest bank-holding companies. “They’re moving from a disinterested nonprofit that couldn’t do the job,” exclaims Greenberger, “to an interested for-profit. There’ll be less transparency I bet in the way that rates are set.”

Chilton is equally apprehensive at the idea of the transition: “When there’s a profit motive, I think it’s always suspect. That’s why key benchmark rates like LIBOR in my view should be monitored or overseen by either a government entity, a quasi-government entity or a not-for-profit third party that doesn’t have a vested interest in what the rates should be.”

How LIBOR will be determined in the future is still being hashed out. A spokesperson for NYSE Euronext declined to answer the Press’ questions on the record, instead directing us to their standard press release. Most observers agree, however, that the days of aggregating estimates should be a thing of the past.

“These benchmarks need to be based upon actual trades,” says Chilton, “not a poll of what the money movers believe it should be.”

As far as the bankers’ claims that price-fixing was a victimless crime, there are several municipalities that beg to disagree. The cities of Baltimore and Philadelphia, among others, have filed suit against several banks claiming severe financial injury due to LIBOR manipulation.

“That’s the hidden story of Detroit,” says Greenberger. “Detroit got clobbered in the swaps market.”

“That’s the hidden story of Detroit,” says Greenberger. “Detroit got clobbered in the swaps market.”

Greenberger also warns that “pensions are still in this market.” That’s a scary proposition considering the underlying risk and leverage that still exists off bank balance sheets.

Eric Sumberg, the spokesman for the New York State Common Retirement Fund—the nation’s third-largest pension—says State Comptroller Tom DiNapoli is watching the LIBOR transition closely.

“There have been some calls for moving from LIBOR’s banker’s poll to a rate-setting process that is more directly based on a broader universe of transactions and on actual market activity,” Sumberg wrote the Press in response to our inquiries. “Such a change over time could have the potential to improve transparency and integrity in rate-setting, but potential details of any such process have not yet emerged. We will continue to monitor developments in this area.”

Yet even when the proposed rules are made public and the administration of LIBOR has fully transitioned, NYSE Euronext will still only be the titular head of LIBOR. The real force behind the market is neither in London nor New York. Atlanta, home of the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE), is the new financial capital of the world.

ICE IN HIS VEINS

CEO of the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE).

Photo taken from the

2012 ICE annual report.

Many of the toxic assets the public became aware of after the 2008 crash have worked their way through the system and been mostly written off by many of the largest financial institutions. Much of the credit for the industry’s stunning recovery belongs to the U.S. Federal Reserve’s low interest rate policy and aggressive liquidity practices known as quantitative easing. Much like the exuberance that preceded both the tech-bubble crash of 2000 and the mortgage-backed securities crash of 2008, a capital bubble established by the Federal Reserve is artificially propping up the market.

Hedge funds and bank holding companies fueled their own recovery by using deposits, borrowed federal funds and leverage to drive the equity market to historic highs and post speculative profits in the derivatives market. And while the financial sector was scrambling to regain its footing, regulators in Washington, D.C., attempted to keep pace by passing reforms to prevent the next global financial crisis should the Federal Reserve change course and remove liquidity from the system while simultaneously allowing interest rates to gradually climb.

In 2010, Congress passed the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in an effort to curb speculation and create greater oversight in the financial sector. It was a monumental legislative task that has proven even more difficult to translate into regulatory policy. Regulators at the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission have been working against bank lobbyists and the fact that the markets are global and U.S. regulatory authority only reaches so far.

To complicate matters further, banks have been busy changing the rules of engagement by shifting markets from classic bilateral swaps between parties to futures contracts, which are more standardized agreements traded on exchanges and therefore subject to greater regulatory scrutiny. In theory, exchange-traded derivatives will provide the transparency that regulators seek. In practice, however, this capital shift might simply move risky investments from the frying pan into the fire, as futures exchanges are global, meaning U.S. regulators must rely heavily on the voluntary cooperation of foreign exchanges.

The one person set to benefit from this capital shift is Jeffrey Sprecher, founding chairman of the ICE. Though not a household name outside of investment circles, Sprecher has emerged as the unlikely king of the global trading exchange industry. In little more than a decade, he helped transform the commodities market from a $10 billion market to more than a half a trillion dollars, with the ICE being a huge beneficiary.

The growth of trading on the ICE has been so explosive Sprecher is about to close on a deal to purchase the vaunted NYSE Euronext for $8.2 billion. The deal has already been approved by European regulators and awaits final approval in the U.S. Once completed, Sprecher will not only run the world’s most famous trading exchange; he will also extend his reach into the global derivatives market as the acquisition includes NYSE Liffe, one of the world’s largest derivatives trading desks.

Nathaniel Popper’s front-page story in the business section of The New York Times on Jan. 20, 2013 pulls the veil back on Sprecher, the man, and describes how he grew a little-known Southern exchange into a juggernaut capable of purchasing NYSE. As Popper himself writes, “It sounds preposterous.” Given the inevitable capital shift sparked by U.S. regulators, Popper also notes that “Wall Street firms will have to move trading in many opaque financial products to exchanges, and ICE is in a perfect position to profit.”

Popper’s piece brings forward a story that few people know. Most have no idea that trading exchanges are even for-profit businesses. And while he does a worthy job demystifying the business of exchanges, he overlooks the planet-sized regulatory loopholes that allowed Sprecher to convert a small energy futures trading exchange into a global exchange that is buying the most famous trading platform on Earth.

To call Sprecher an opportunist would be technically accurate but cheap and intellectually dishonest. He understood the inevitability of electronic trading and the superior potential it held. But there’s a danger in spreading the accepted mythology of Jeff Sprecher and his plucky exchange. Behind his story is the familiar invisible hand of Wall Street.

“The reason Sprecher has been so successful is he’s really representing all the major ‘too big to fail’ banks,” says Greenberger. “And they want him to succeed, and therefore he is succeeding.”

Missing from the brief history of the ICE are the loopholes that gave it life and the ability to flourish beyond imagination. It was the oft-spoken of— but rarely understood—“Enron Loophole” that gave corporations the legal right to trade energy futures on exchanges such as the ICE even if the corporation itself was in the business of energy. The second loophole was a maneuver by the Bush Administration that granted the ICE foreign status as an exchange despite its being based in Atlanta. This initiated a massive shift of trading dollars, and influx of new ones, into the ICE for one reason: This singular move placed the ICE outside the purview of U.S. regulators like Chilton at the Commodities Futures and Trading Commission (CFTC). Essentially, corporations could now trade energy futures electronically through the ICE without oversight or disclosure.

Moreover, the mere fact that the founding investors of the ICE are some of the world’s largest bank-holding companies, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs in particular, speaks to how little transparency there truly is.

This in no way takes away from Sprecher’s genius as a businessman. It simply illustrates how willfully ignorant we are to the business of Wall Street and therefore how frightfully far away we are from properly regulating it. Everything Sprecher has done is legal and ethical, to the extent there is an ethos on Wall Street. Where all of this hits home for the consumer is at places like the gas pump and the supermarket.

Now it’s easier to place the LIBOR issue in its proper context. Almost every “too big to fail” bank has a significant ownership stake in both the ICE and NYSE Euronext, soon to be one entity. This combined entity will also soon control LIBOR, the world’s largest rate-setting mechanism. In trader’s parlance, this would be considered the perfect “corner.”

But wait, there’s more. In the attempt to rein in speculation and manage risk in the marketplace, Dodd-Frank might have unintentionally become the gift that keeps on giving—to Sprecher.

THE FUTURE OF FUTURES

The sheer size and complexity of the derivatives market overwhelm even the most interested parties—including Congress, regulators and bankers themselves—leaving average citizens utterly dumbfounded and sidelined. It’s little wonder. Banks that were too big to fail in 2008 are bigger today in 2013. The vast majority of the much-ballyhooed Dodd-Frank regulations have yet to take effect, and bank leverage is back at pre-crash levels.

A former trader who worked in both New York and London recently told me, “At the end of the day, this market is running on the [Federal Reserve]. Once they pull out it’s all over. Cheap money, loads of people making loads of money, but no lessons learned.”

A former trader who worked in both New York and London recently told me, “At the end of the day, this market is running on the [Federal Reserve]. Once they pull out it’s all over. Cheap money, loads of people making loads of money, but no lessons learned.”

Derivatives themselves aren’t nearly as difficult to understand as the markets they trade in. They are essentially risk transfer agreements between two parties, a way to hedge investments. The word ‘derivative’ refers to the fact that the agreement derives value from other investments: a bet as to how the original investment would perform. It’s helpful to once again employ the casino analogy.

Ten random players approach the roulette table and lay down $100 worth of chips on various numbers. Each individual gambler is making a bet, or an investment, collectively totaling $1,000.

Now imagine that another gambler watching the action on the roulette table calls his or her bookie and places a bet on the outcome of their total wagers when the wheel stops spinning. Having sized up the situation, the gambler predicts that overall this group will win and walk away with $1,100. But in order for this bet to be placed, someone else has to take the action and bet the group will lose $100, leaving them with $900. Before the ball drops on the number, the bookie connects the two outside gamblers and creates a new bet. This bet functions as the derivative investment because even though they’re not actually playing the game, they have a stake in the outcome.

In the real world of investing, the bookie is a trader and the gambler taking the action from the outside is a speculator. Sounds nefarious, but in reality, these transactions are essential to providing market stability.

“If we didn’t have speculators,” says Chilton, the CFTC commissioner, “consumers would pay disproportionate prices.”

There are three classic types of derivatives, all of which Chilton and the CFTC have been trying to rein in well before the crash introduced the world to this type of investment. All three involve counterparties, which trade these investments either directly or through exchanges.

But the differences between the three types of derivatives are diminishing. The first type of derivative is commonly referred to as a “swap.” This is where two parties exchange risk with one another in a negotiated agreement. In the United States, these have traditionally been deals between banks that fall under the purview of the SEC. The other two types of derivatives, futures and cleared derivatives, are negotiated similarly but must be listed and cleared on exchanges.

The CFTC and other regulators have long argued that these investments are similar in nature and should therefore be consistently regulated with complete transparency. With the exception of swaps, the investment created at Salomon Brothers in the 1980s, this was historically the case. But despite the similarity between swaps and other types of cleared derivatives, regulators allowed swaps to be treated as banking instruments that were held “off balance sheet.” Over the next two decades a flurry of deregulation and the growth of global trading reduced the transparency of derivatives trading and increased the size of the market dramatically.

The Dodd-Frank regulations were designed to put an end to this practice by requiring anyone who deals in large amounts of swaps to register as a swaps dealer and clear their trades through an exchange. Yet CNBC’s John Carney believes the new swaps regulations have already created a “flight to futures” from swaps, an unintended consequence of Dodd-Frank that will end up with a “world with less collateral and less capital, less transparency, less investor protection, more concentration of risk, and a huge unanticipated market transformation.”

In other words, the ICE will likely be the greatest beneficiary of Dodd-Frank.

Nevertheless, Chilton believes that there will still be “trillions, tens of trillions if not hundreds of trillions of swaps that will be traded in the U.S. and worldwide that will be regulated and have the light of day cast upon them.”

For his part, Greenberger agrees U.S. regulators are beginning to get a handle on the markets but thinks inordinate risk is still present in the market. He calls the original Dodd-Frank a “Rube Goldberg system” that was “prospective in nature. There’s still trillions of dollars of swaps that are operating in an unregulated environment.”

The world will have to hold its breath until these unregulated swaps run their course and settle in the global marketplace. Intelligent reforms such as margin and capital requirements, position limits and cross-border coordination with respect to regulation are indeed around the corner. These reforms essentially mandate that everyone involved in trading these agreements has enough money to cover potential losses and plays by the same set of rules.

“Ultimately we will have position limits,” Chilton believes. “I would be surprised if they weren’t in place by the end of the year.”

Greenberger also believes the world will begin to recognize universal standards, saying: “The CFTC has made it clear that for futures the foreign exchanges have to comply with U.S. rules.”

Even still, he worries that “this international guidance is a roadmap for banks to avoid Dodd Frank. Just trade in foreign subsidiaries.”

Chilton takes a more sanguine view on immediate concerns such as transparency, working with his European counterparts and the future of LIBOR, but he worries more about the things he cannot see.

“I feel like we’re going to get things done on capital requirements and on cross-border stuff so that other regulators come to where we are,” says Chilton. “But there’s a bunch of new things that are around the corner that we can’t see.”

He cites high-speed trading computers that he calls “cheetah traders” as an example of the unknown. “The cheetah traders, the high-frequency traders, are proliferating. They’re 30 to 50 percent of markets on average but during feeding frenzy time, cheetahs can be up to 70 or 80 percent of the market. There’s not one single word in the Dodd Frank legislation that deals with high-frequency trading. Not one word.”

Once again, pulling the strings behind this unseen phenomenon is Sprecher, the man responsible for making high-frequency trading what it is today.

Thomas Jasper will likely never get that plaque for inventing the investment world’s biggest game of chance. On a positive note, however, he’s alive, well and wealthy, unlike Moe Greene, who infamously took a bullet through the eye. But there are better-than-even odds that a statue of Jeff Sprecher will someday be erected on Wall Street. Or, at the very least, downtown Atlanta.