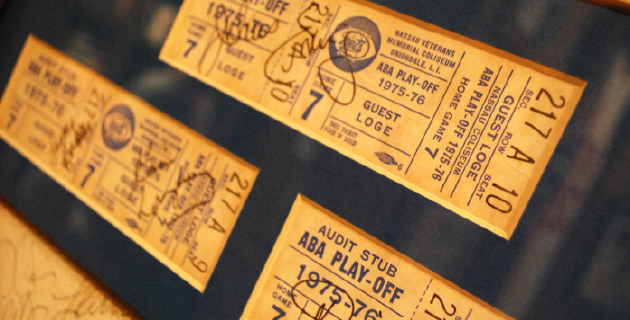

Shrieks of joy reverberated through Nassau Coliseum as jubilant New York Nets fans rushed the court with just three seconds left to go in the 1976 American Basketball Association (ABA) championship.

Nets forward Rich Jones had just flicked a layup through the net, giving the Nets a 112-106 lead over the Denver Nuggets, the bucket sewing up the Nets’ second ABA title in three seasons.

“Pandemonium!” the broadcaster blared over the airwaves.

The Nets barreled into their locker room, sharing sweaty hugs and champagne showers. Julius Erving—the pride of Hempstead and Roosevelt, and the best player in the league—emptied a bottle onto a reporter’s head and smiled.

“It’s as sweet as it ever was, I tell ya,” he exhaled.

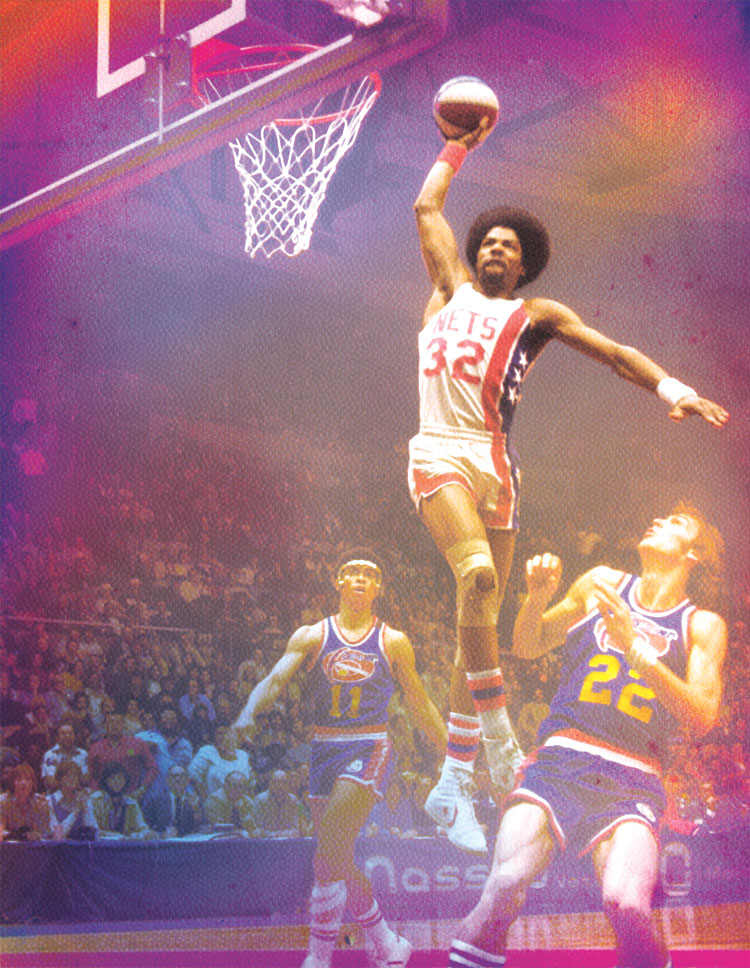

Erving, the league’s most popular player and a three-time ABA MVP—all with the Nets—scored 31 points as he led a dizzying comeback that saw his team erase a 22-point deficit with 17 minutes left in Game 6. It was another historic achievement for the hometown kid whose rim-rattling dunks had been revolutionizing basketball and inspiring legions of youngsters, such as future Chicago Bulls legend Michael Jordan—who’s now considered the greatest, ever.

Yet before Jordan dazzled crowds with his high-octane performances, it was Erving who filled the usually sparse ABA arenas with his above-the-rim game and rocket-like adventures soaring through the air.

Because ABA games weren’t nationally televised—back then National Basketball Association games were—much of what the country knew of Erving they had read in newspapers or Sports Illustrated, which put Erving on its cover the week after the finals with the headline: “Dr. J Slices ‘Em Up.”

“Too bad, America, but you missed one of the greatest basketball shows on Earth,” Pat Putnam wrote in the May 17, 1976 issue of SI. “Or, rather, one just a few feet off the Earth. That was Julius Erving last week, launching himself from various points on courts in Denver and New York, soaring and scoring, passing, rebounding, blocking and stealing—all in the undeserved obscurity of the ABA championship finals. By Saturday night Erving and his underdog New York Nets had Denver down three games to one, which is what can happen when humans go five-on-one with a helicopter.”

Erving would take off from Long Island that summer, never to return to the Nets again. The greatest player in the team’s brief, nine-year history on LI was entangled in a contract dispute following the ’76 season, and Roy Boe, the Nets owner, then struggling to pay the enormous entrance fees to get his team into the NBA, sold Erving to the Philadelphia 76ers. There he’d win yet another championship, catapulting “The Doctor” to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

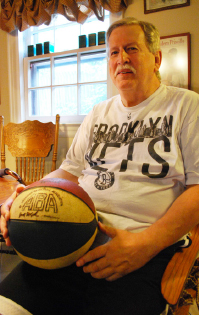

Although the world’s sports fans may not have gotten a chance to watch Dr. J’s dominance from the comfort of their living rooms, the memories of Erving and the Nets’ exploits on LI from 1967 to 1976 are forever ingrained in the minds of those lucky few who witnessed some of the most exciting—and comical—basketball of any generation firsthand.

Basketball Boondocks

In 1967, Arthur Brown purchased the New York Americans with the goal of developing a New York-based franchise for the upstart ABA. But Brown failed to get an arena deal and was forced to set up shop across the Hudson, at the Teaneck Armory in New Jersey—a cavernous monolith that only seated 3,500.

The Americans had a lousy inaugural season (24-58) in Jersey, but miraculously tied for the final playoff spot because the other ABA teams were just as woeful. The folks running the Armory hadn’t planned on the Nets advancing to the postseason, though, and had booked a circus event there instead.

That’s when the Americans made their first trip to the Long Island Arena, aka Commack Arena.

“Well, we got out there; the facility was in terrible shape,” recalls Turetzky. “The floor had holes in it, cracks, warps, and it was really unfit to use, and we couldn’t play the game. We ended up forfeiting the game to the Kentucky Colonels, and that was the end of our season.”

Despite the Arena’s faulty hardwood floor and freezing temperatures inside, Brown relocated the team to Commack for the 1968-1969 season and renamed them the Nets—supposedly to make the team rhyme with the Jets and Mets—before fashion entrepreneur, Roy Boe, purchased the team and moved it to Island Garden in West Hempstead.

It’s a wonder the Nets actually played an entire season in there.

“Visiting teams would get dressed at their hotel and come to the Arena in their warm-ups, because the locker rooms were freezing,” Turetzky says. Some players on the bench opted to wear overcoats over their red, white and blue jerseys and refused to disrobe until they were coming into the game.

The minor league hockey team known as the Long Island Ducks also called Commack Arena home. Once condensation from the ice rink seeped through the court floor so severely that officials had to cancel a Nets preseason game—nearly sparking a riot outside.

“The court was so slippery,” laughs Don Ryan, a Hempstead village trustee who coached Erving on Hempstead’s Salvation Army team. “I mean it was almost like we were some sort of prelim for comedy or something.”

Real change finally came in 1974 in the form of a high-flying, charismatic forward with a funny nickname, who, as rumor had it, glided poetically over defenders, whirling his body in strange positions, stretching his arms like they were molded out of clay, and almost hiding the red, white and blue basketball in his enormous hands. And he came to town just in time for the Nassau Coliseum’s opening in Uniondale.

The Operating Room is Open

The Nets scored Erving in a complicated $4-million package in 1973.

“I mean, there were so many players and agents and team executives and league officials involved, and we were spending so much money in legal fees, it was just insane,” Boe, the Nets owner, told Vincent Mallozzi for his book, Doc: The Rise and Rise of Julius Erving.

Erving had begun playing recreation ball in Hempstead for the local Salvation Army team when he was 12 before starring at Roosevelt High School and eventually the University of Massachusetts. He landed in Nassau County with much fanfare after averaging 32 points per game the previous year with Virginia.

“Coming back to Long Island, life could not have been better,” Erving said in The Doctor, an NBA TV documentary, which premiered last June. “My time here, my era here, I think was very special.”

For Ryan, the Hempstead village trustee and coach, Erving’s arrival meant a reconnection with his former star player, who had walked into his gym, now a half-century ago, with raw talent and sheer determination.

“He got better every day,” Ryan recalls, two black-and-white photos of a teenage Erving splayed across a table.

Ryan proudly shares a May 2005 New York Post article in which Erving compares his fondest memory in the ABA to Ryan’s teams in Hempstead.

“The first year in Virginia was almost like going back to my basketball days with the Salvation Army,” Erving told the paper.

When he stepped out on the Coliseum’s court, Erving didn’t experience the hometown jitters that have befuddled other athletes playing in front of friends and families.

“The Doctor” averaged 27 points per game in his first season with the team and was crowned the league’s MVP, leading the Nets to their first ABA title. Erving was awarded MVP honors the next season, but the Nets failed to capture back-to-back titles. Everything came together for the Nets in their final season in the ABA, finishing second in the standings with a 55-29 record and dropping the Nuggets in six games in the finals.

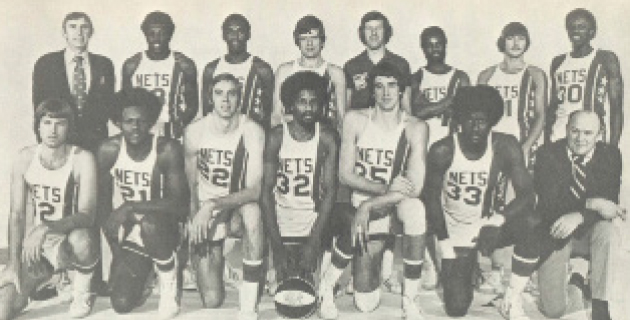

Front Row (left to right): Chuck Terry, Tim Bassett, Jim Eakins, Julius Erving, Kim Hughes, Rich Jones, Trainer Fritz Massman. Back Row (left to right): Owner Roy Boe, John Williamson, Ted McClain, Assistant Coach Bill Melchionni, Coach Kevin Loughery, Brian Taylor, George Bucci, Al Skinner.

“Julius is among a group of players from the 1960s and the 1970s who epitomized style and cool,” states Bob Costas, who was also raised on LI, in Mallozzi’s Erving biography. “This guy was so much cooler than 95 percent of the athletes playing today, it’s a joke. He played the game with such style, such flair, but he never did it in away that showed up an opponent, or to show off in front of a crowd.”

New York Knicks legend Walt “Clyde” Frazier laughs today when asked what it was like to play against Erving—possibly due to his memories of Erving’s legendary flights to the basket.

“He was intimidating,” Frazier tells the Press. “He was magical on the court, flamboyant on the court.”

Nate “Tiny” Archibald, who played in the Nets final season at Nassau Coliseum when the NBA absorbed the team, lamented missing out on the opportunity to run alongside Erving.

“I came from Kansas City to Long Island,” Archibald says. “It was great coming to New York…I thought I was going to play with Erving. I was ecstatic about the trade.”

Like Archibald, the Nets fans were crushed. Many of them lashed out at Boe for selling Erving to Philadelphia. ABA historians liken Boe’s decision to sell the All-Star forward to that of Boston Red Sox owner Harry Frazee’s December 1919 sale of Babe Ruth to the New York Yankees. In Erving’s finest moment as a Net, the 1976 championship, the future of the team and a possible dynasty were all on his mind.

“Now, hopefully, we started something that we can keep and win some more championships in the years to come,” Erving told the cameras amid the champagne-filled celebration. “But we’re going to enjoy this one right now.”

The Nets haven’t lifted a championship trophy ever since.

—With Carly Rome