After the residents moved out of their Central Islip house following Superstorm Sandy last year, squatters eventually seized the opportunity to claim it as their own, make themselves at home and smoke some crack cocaine.

The light blue one-story ranch on a dead end with a big overgrown yard tucked between an industrial complex and an empty lot overlooking a junkyard made an ideal crack house—except for the fact that it’s about 1,000 feet across the railroad tracks from an MTA Police station.

The windows aren’t boarded up or broken. The home-security alarm sign on the lawn gives the illusion that some upstanding citizens still live inside. One neighbor says she hadn’t noticed anyone new there.

“It’s quiet here,” the neighbor says. “One time I saw a car here, I called and they got rid of it.”

But what Suffolk County police said they found inside belied the mostly undisturbed facade facing East End Avenue. It was a nondescript version of derelict properties left unmaintained by absentee landlords, homeowners that couldn’t pay their mortgages or lenders that foreclosed—magnets for drugs, prostitution, squatters and burglars that steal copper pipes to sell for scrap.

“It ain’t my house but if I come inside I got squatters rights,” James Jones allegedly told Suffolk police officers in September when they arrested him and three others accused of smoking crack in the house in September, court records show. “Everybody smoked rock in here, but they ain’t no rock in here now.”

Rock, for the uninitiated, is slang for crack. The address Jones gave police as his home was another foreclosed house a dozen blocks away at 405 Ackerman Street, one of 157 the Town of Islip boarded up so far this year, up from 69 last year and 35 in 2011. Sources with knowledge of the investigation say beds were rented out for $3.50 nightly in the Central Islip house, which had no plumbing and feces littering the yard.

While police have been dealing with crack for 30 years, squatters have been increasingly frustrating police in the five years since the 2008 housing bubble burst and the ensuing financial crisis sparked an explosion of foreclosed homes nationwide. Local lawmakers, authorities and neighborhood watches especially have their work cut out for them fighting some of the nation’s worst foreclosure rates on Long Island, where minority areas hit harder than others buck recovery, threatening the entire region.

New York State had the third-highest number of homes in foreclosure in the nation—5 percent of mortgages, with 8 percent more in serious delinquency—behind Florida and New Jersey as of August, according to analytics firm CoreLogic’s latest report this summer.

CoreLogic found in March that Nassau and Suffolk counties combined had the highest rate of houses in foreclosure statewide, totaling the third-highest percentage of foreclosures in any major metropolitan market outside The Sunshine State.

Central Islip had the highest volume, rate and concentration of foreclosures in Suffolk based on 90-day Pre-Foreclosure Filing Notices recorded by the state Department of Financial Services through last summer, ahead of Brentwood, Wyandanch, Shirley and Bay Shore, according to a report this spring by the nonprofit Empire Justice Center.

That all adds up to a lot of headaches for neighbors of foreclosed, vacant homes who fear—and sometimes face—reprisals from reporting to police that the crooks have moved in next door, since many low-level offenders return soon after authorities take action.

“Everybody’s afraid,” says Brian McCluskey, the outspoken head of the South Bay Shore Civic Association, who doesn’t count himself among the fearful. “The bad guys are not afraid…because they got nothing to lose. Somebody has to stand up.”

STREET HASSLE

McCluskey, a 72-year-old retired Wall Street trader and Jack LaLanne-type whose anti-crime rants sometimes border on advocating vigilantism, had gotten into a fight with his neighbor who was throwing a rave this summer, and he was returning home for his mouth guard to go another round when police arrived.

Until recently Jason Nagy, a convicted child rapist and registered sex offender, lived near McCluskey in a house Bank of America recouped from prior owners who had failed to pay their mortgage. Nagy’s address on the sex offender registry was still listed at that house as of press time.

“I go down there and say, ‘Jason, close it down!’” recalls McCluskey, the only one of a handful of residents contacted by the Press willing to share his story of confronting a neighboring squatter. “He says, ‘Come on, I’m just trying to make two bucks a head!’”

The house is one of three distressed properties, including two boarded-up houses that McCluskey termed “shooting galleries”—used not for firing guns, but injecting heroin—on Bay Avenue, a narrow service road to historic mansions south of Montauk Highway.

“Property owners have a responsibility to care for, secure and maintain their assets, and banks and mortgage companies also have a legal responsibility to care for and maintain the properties that they manage or that they hold,” says Inez Bibiglia, spokeswoman for Islip town.

Touting last month’s boarding up of the Ackerman Street crack house, she says: “It’s boarded up, it’s secure now, that’s the point. However, these poor people have to live next to this for how long?”

A lot of Long Islanders have the same question.

DIRTY BOULEVARD

McCluskey may settle that debate with a more hands-on approach than most folks, but most-impacted municipalities are doubling efforts to tamp back the flames of foreclosure.

Suffolk being geographically larger than Nassau, the 10 easternmost towns appear to confront the problem more than the three west of the county line. But foreclosures were most pronounced in minority communities in both counties, Empire Justice Center found.

“In the wake of the foreclosure crisis, hundreds of homes have been abandoned across our town,” Brookhaven Town Supervisor Ed Romaine said of a proposed $100 annual vacant-home registration fee to complement LI’s first housing-violation reporting smartphone app.

“While the previous owners vacated these houses, they are still owned by someone—whether it be a bank, a corporation or some other entity,” he said. “This law makes clear to those owners that they are just as responsible for maintaining their property as the hardworking families who live here.”

Brookhaven boarded up 307 vacant homes last year and 326 so far this year as of October. The town also bulldozes blighted properties semi-regularly.

Since the Town of Huntington passed its law cracking down on blight in 2011, code enforcers cited 108 properties, which aren’t necessarily foreclosed, a town spokesman says. Fifty two have been cleaned up. Suffolk police also busted a party with nearly 600 people in a vacant warehouse in Huntington Station last month.

Kevin Bonner, a deputy Babylon town supervisor, says the town scheduled meetings with banks and other owners of houses who hold 11 properties on that town’s new abandoned house registry, which may soon be bolstered.

Riverhead officials said they sent notices of violations to 40 nuisance properties last year but only three ended in town action. Town of Smithtown officials say the number of times the town board ordered properties cleaned up doubled in the past year from two in 2012 to four in ‘13. A North Hempstead town spokesman said its workers cleaned up 14 properties since October 2012.

Southampton, East Hampton and Oyster Bay town officials said derelict properties are secured when town supervisors learn to direct staff to a particular address and were unable to provide statistics. Stats were also unavailable for the towns of Shelter Island, Southold and Hempstead—the southwest corner of Nassau that Empire Justice Center found had the seven communities most impacted by foreclosures in that county.

How effective the efforts in any of these towns will be remains to be seen.

HANGIN’ ROUND

Squatters breaking back into boarded-up houses. Scrappers stealing copper pipes from houses without turning off the water or gas lines first, causing leaks. Derelict properties full of suspicious characters right across the street from schools.

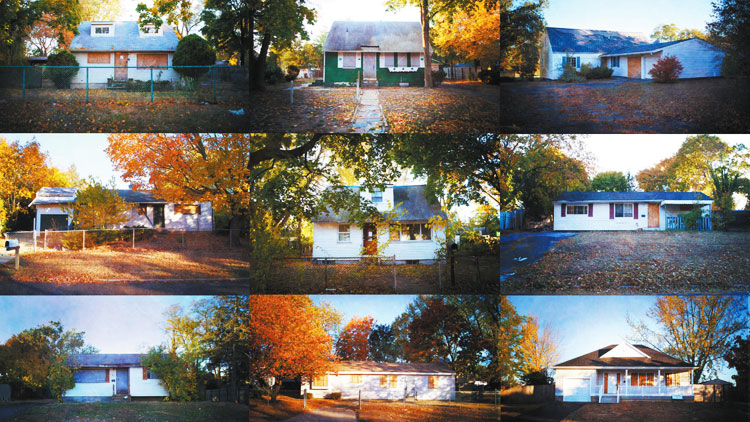

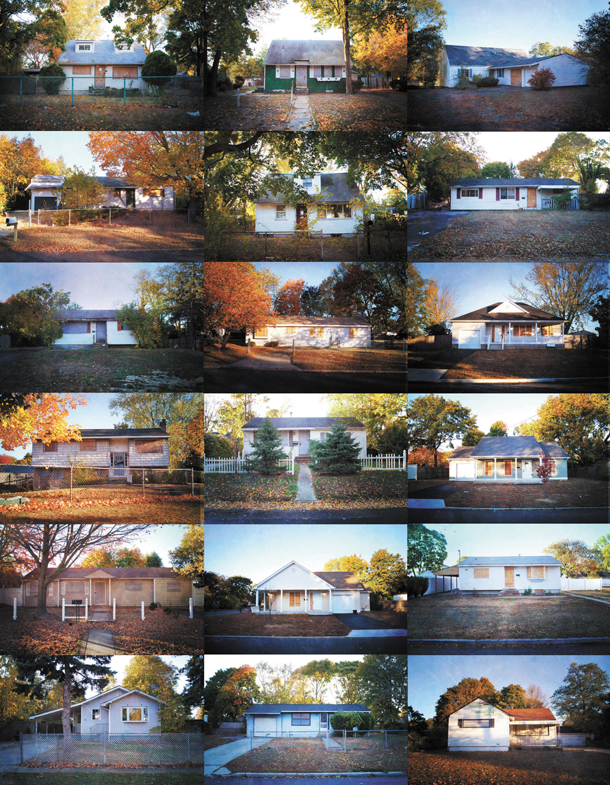

On a recent October morning Chris Pross, the Central Islip Fire District fire marshal, drives by houses such as these and dozens more during one of his regular vacant-house patrols in his department-issued SUV with this reporter riding shotgun. “No copper” is spray-painted in big black letters on the sealed front door of one boarded-up house, a message to would-be thieves not to waste their time.

“That’s a telltale indicator,” Pross says, pointing to a pair of junk-filled shopping carts outside an open basement door behind a boarded-up house on St. Johns Street, where squatters ripped boards from three windows. “There’s at least one or two guys in there.”

He counts 116 derelict properties that are either secured or have been boarded up within the fire district, nine of which he terms unsecured. Some are so structurally unsafe, firefighters can’t risk going inside if a fire breaks out. And those are only the ones Pross is aware of.

When a 45-year-old squatter lit a fire in the basement of a derelict home on Sycamore Street to keep warm on a cold night in January, the fire department was unaware the house was vacant until it burned down, killing him inside. Two firefighters were hurt responding to that blaze.

“These are the ones that are potentially dangerous,” he says outside the burned-out house that could have spread to a neighboring home full of sleeping residents—some of which may be illegally subdivided multi-family dwellings packed with more potential victims.

Pross, who lives in the neighborhood, has a trained eye that can spot a house of suspected squatters just by glancing at the windows. He worked in the same capacity for Islip Town since ’87 until the fire district—concerned with a lack of code enforcement in the area—hired him the year before the ’08 Wall Street crash. Despite the overwhelming number of blighted properties, he sees progress.

“Every block east of Lowell Avenue…had at least two vacant homes on it at one point, and I was worried that this place was going to become like Detroit,” Pross says, estimating that the rate is now more like one on every other block. “But it’s starting to bounce back, thankfully.”

SHELTERED LIFE

Pross isn’t the only one banking on a comeback.

John Rizzo, chief economist for the Long Island Association, issued a statement last month spinning recent declines in The National Association of Realtors’ Pending Home Sales Index as good news.

“This pattern may reflect higher mortgage rates and rising home prices,” said Rizzo, who is also a professor of economics at Stony Brook University.

“This is a positive sign for the housing recovery,” he said. “Despite today’s results for pending sales, year-over-year actual sales in September 2013 were 10.7 percent higher, the 27th consecutive year-over-year increase. Moreover, the recent decline in mortgage rates may serve to bolster sales going forward.”

Ruhi Maker, an attorney with the Empire Justice Center who helped compile the nonprofit’s report investigating LI’s foreclosure crisis this spring, cautions that it may be too soon to start popping champagne.

“If [people] are only reading the national media or if they’re only looking at the county-level data, they’re thinking the problem doesn’t exist,” she says. “But when you go down to the census track data, the block data or the zip code data, you start seeing that it’s like two nations.”

For example, the Suffolk County clerk’s office noted in its annual report that 589 Judgments of Foreclosure were filed last year, down from 722 in 2011. But the Empire Justice Center report found that 10 of the 94 zip codes in the county accounted for 34 percent of 90-day foreclosure notices through the second quarter of 2012.

She notes that the impacts of Central Islip having the densest amount of foreclosures in Suffolk—thanks, in part, to the state’s extra-slow foreclosure process—are lagging demand and home prices continuing to fall in the community this year, while both rise elsewhere.

“It’s sort of like the tip of the iceberg is what your seeing right now,” Maker says. “We haven’t reached bottom… Although it may already be bad, there’s potential for it to get worse.”

The stunted economic recovery may be setting up another wave of foreclosures in similarly low-income minority communities, where homeowners often have the most difficulty in securing home-loan modifications, she warns.

“Some people are doing well, some people are getting raises, some people are getting jobs,” Maker says. “But there’s an equal number of people who aren’t getting raises, who aren’t getting jobs, who therefore still can’t afford their mortgages and who are still at risk for foreclosure.”

FOGGY NOTION

State, county and town-level lawmakers frequently tout efforts to reclaim blighted properties, rebuild them and help families—prioritizing first-time homeowners—move in. Although in some cases, the new homes come with a view of a neighboring run-down house.

“Besides boarding them up, how do we get them with families living in them?” Islip Town Councilman Steve Flotteron asks rhetorically. “Take the weakest home on the street and slowly it’ll be the strongest because those homes will be refurbished with new homeowners who are creditworthy that the Long Island Housing Partnership screens and educates to make sure they’re stable to buy the home.”

While nonprofits such as LIHP also try to stem foreclosures by advocating in court for homeowners who lenders seek requests for judicial intervention against, often there’s little stopping houses from landing in legal limbo for years.

Joining in the vacant-home reclaiming efforts is the Suffolk County Land Bank Corporation, one of 10 nonprofits created by a 2011 state law that can acquire vacant, abandoned or foreclosed properties and raze, rebuild or remodel them.

New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, who granted $675,000 to the Suffolk land bank last month using last year’s National Mortgage Settlement with the nation’s largest banks, said such initiatives are “helping to empower local communities to rebuild their own neighborhoods, house by house, block by block.”

Proceeds from the resale of renovated properties will go back to the land banks to fund future redevelopments, which will also be financed by private and public funding, such as grants from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

“Two years ago, when I saw these abandoned and polluted properties littering the county, I knew that we had to do something,” said Majority Leader DuWayne Gregory (D-Amityville), whose district includes some of the hardest-hit areas. “This grant will finally allow us to start reclaiming the worst of these blighted parcels, and in the process, also revitalize neighborhoods around them.”

WILD SIDE

In the meantime, squatters like Jones of Central Islip and Nagy of Bay Shore will likely be settling into the nicest abandoned homes they can find before winter puts the region into a deep freeze.

Some may even go as far as to mow the lawn, trim the hedges and make home repairs to keep up appearances in hopes of forestalling being tossed to the curb, according to Pross, the fire marshal.

But experts say it’s almost unheard of for squatters to legally stake a claim of squatters’ rights in landlord-tenant court and succeed in obtaining a house they acquired in a hostile takeover through the law of adverse possession, which requires a decade of possession in New York State.

“I’ve dealt with it once or twice, but it is a bigger issue in the city than on Long Island,” says Elliot Schlissel, a Lynbrook-based foreclosure defense attorney, noting that it’s likelier that a bank rents a house back to the owners the lender foreclosed on. “The issue of squatters is: Do you need to evict them [through the courts] or can you just throw them out?”

Civic leaders like McCluskey would be glad to help show such squatters the door. It’s keeping them from coming back that’s proven difficult. For police tasked with combating the issue, it can be like a bad game of whack-a-mole.

“If there’s a spot where a drug dealer can set up and do his business off the street, they exploit that,” says Sgt. Daniel Fischer of the Third Precinct Community Oriented Police Enforcement (COPE) Unit. “We close one, and they move on to the other.”

As long as everyone works together, eventually there should be fewer vacant houses in these communities in which criminals can hide. For now, it’s hard not to drive around and spot houses that evoke the recently bankrupted Motor City.