On Dec. 7, 1993 a crowded Long Island Rail Road train left Penn Station at rush hour. As countless Long Islanders can still recall, a tragedy unfolded between New Hyde Park and Merillon Avenue.

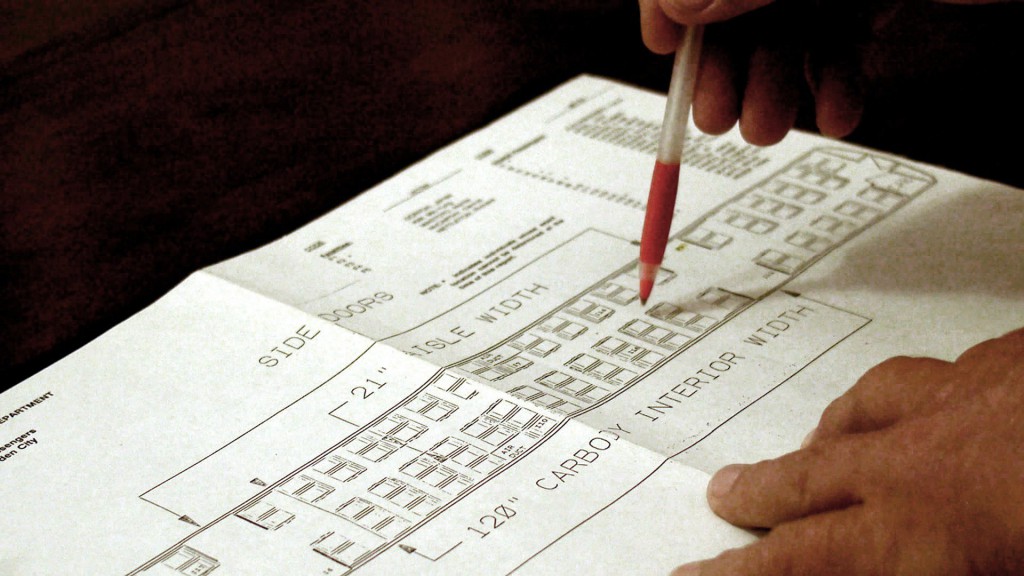

Four passengers left their lives onboard and 21 others were wounded, two fatally, when a deranged gunman named Colin Ferguson got up from his seat and came down the aisle. He fired two clips of 15 bullets each, and was about to load another when three men jumped him and pinned him to the ground.

All the horror of the shooting, the pain of the aftermath and the outrage of the infuriating trial are brought back vividly to life in Charlie Minn’s powerful new documentary The Long Island Railroad Massacre: 20 Years Later, which opens in select theatres on Nov. 15.

The random and the routine normally in people’s lives were suddenly caught in the deadly crosshairs of a deliberate act of violence perpetrated by a very sick man. Some riders just happened to catch the 5:33 p.m. that fateful day, while others rode it regularly. But in that one horrible moment they were all united in a fight for their lives.

The film spares the most gruesome sights of the carnage but its images of the newspapers lying blood-spattered and torn on the aisle floor tell the story poignantly enough to leave a lasting impression.

The project took Minn more than a year as he tracked down the victims, their families, a prosecutor and one of the defense attorneys to recount what happened and how they have adapted since then.

It’s a moving testament to the human spirit.

These days, Carolyn McCarthy is a Congresswoman now in her eighth term representing Nassau’s 4th District. Twenty years ago she was expecting her husband Dennis and son Kevin to put up the Christmas tree before she got home from work. She knew they rode the train home together. But when she pulled into the driveway, the tree hadn’t been touched. Her husband had died in the massacre; her son was critically wounded.

As her son tells the camera: “I thought I was going to die right there.” Yet he survived and had to learn how to walk again.

“You never get closure,” exclaims McCarthy. “But you have to go forward in some way.”

Of the wounded victims, Robert Giugliano’s experience is truly compelling. He saw a woman killed right in front of him, her blood spilling onto his clothes. He was shot in the arm and the chest. At the trial, Giugliano confronted Ferguson, who was allowed to defend himself after dismissing his legal defenders because they wanted him to claim insanity.

Restrained by court guards after leaving the witness stand, Giugliano yelled at Ferguson that he wished he could have five minutes alone with him. Giugliano was filled with righteous rage, but now, 20 years later, Dec. 7 has a mellower meaning for him: It’s his granddaughter’s birthday.

Wave of Mutilation

Then-Nassau County Executive Thomas Gulotta had told the media at the time that “the person who committed this crime is an animal.”

Minn agrees with that sentiment today.

“To me an animal is not racially specific,” explains Minn, who’s Korean-American. “It’s someone who’s not a human being.”

In hindsight, the question of Ferguson’s guilt seems more clear-cut than his level of competence, which allowed him to put the survivors back on the stand so he could face them once again.

“I can’t say I’m an expert with the judicial process,” Minn tells the Press, “but he shouldn’t have been allowed to represent himself in court. To put the victims through that is ridiculous.”

Ferguson had spent two weeks in California so he could qualify for a gun permit. The killer also anted up another $1.50 when the conductor told him he had an off-peak ticket.

“He knew exactly what he was doing,” says Minn. And as Nassau Det. Brian Parpan points out in the film, Ferguson had left a note in his Brooklyn apartment with the heading: “The reason for this…” In court Ferguson claimed he was dozing on the train and that someone else had actually shot the riders.

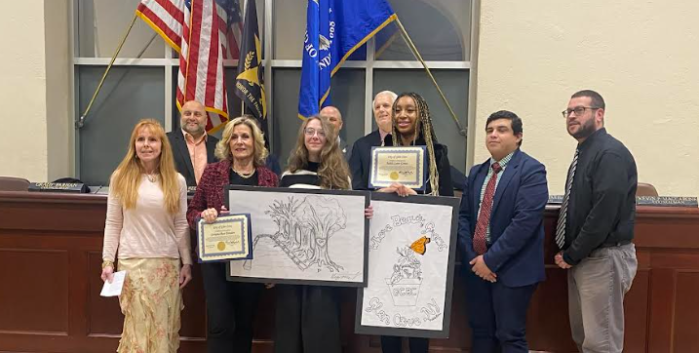

Minn and his co-producers Aaron Michael Thomas and Ken Molestina attempted to contact Ferguson but to no avail. He is currently serving a sentence of 315 years and eight months to life in prison at the Upstate Correctional Facility in Malone, NY, south of the St. Lawrence River. After a recent screening held for the victims at the Shelter Rock Library, Minn is sanguine about not including Ferguson in the documentary since they thought the final cut was better without the convict commenting from his cell.

“They signed off on it,” Minn says, “which meant a lot to me. That was very important because if I didn’t have their approval, it would be hard for me to continue with any passion.”

Minn doesn’t intend this film to be a polemic.

“I didn’t really want to make this film known as a political statement,” he says.

But he has immense respect for Rep. McCarthy.

“To me, Carolyn’s a hero to fight the NRA for 17 years,” Minn says, “and she’s hardly gotten anything passed, yet she trudges along like a good soldier because she sees her husband and her son in her vision.”

He holds out little hope for gun control.

“I think we should get rid of all guns,” he says, “but I realize it’s too late—they’re too far and wide.”

He does think, however, that it’s time people take a hard look at the big picture.

“Who are we as a country?” he asks rhetorically. “Are we a symbol of violence or a symbol of peace?”

Born in Boston, Minn grew up in Manhasset Hills and was attending Herricks High School in New Hyde Park when the shooting occurred. He’s been obsessed with the tragedy ever since, he says, and in part that’s what has driven his line of inquiry: portraying the impact of these kinds of violent crimes through the eyes of their victims.

“Everyone has their own way of dealing with tragedy,” he explains. “Some completely shut themselves off from the world, and then you have people like Carolyn McCarthy who…are very outspoken about it.”

Minn was a chemistry major at Boston University but got his communications degree at SUNY Brockport. He’s done some acting but prefers being on the other side of the camera. His documentary work includes a trilogy on Juarez, Mexico, the so-called “Murder Capital of the World” (also a title of one of his films). This hard-luck city is just across the bridge from El Paso, Texas, which Minn calls his second home when he’s not in New York. The drug-related violence in Mexico, much of it fueled by weapons from the USA, got his attention.

“Over 12,000 people have been slaughtered in Juarez since 2008,” he says. “This is one of the saddest stories in the world today people are not talking about.”

The goal of his work, he says, is to spark the conversation, provide consolation and “honor the victims—never forget the victims.

“My other true crime films are not solved,” says Minn. “This one is solved.”

“The Long Island Railroad Massacre: 20 Years Later” opens Friday, Nov. 15, at Merrick Cinemas on Long Island and the Regal E-walk Cinemas in Manhattan and the Hawthorne Theater in New Jersey. Either the director or a victim of the tragedy will be present at all the screenings on opening weekend in Merrick to take questions from the audience, Minn says. For more information go to www.lirrmassacre.com.