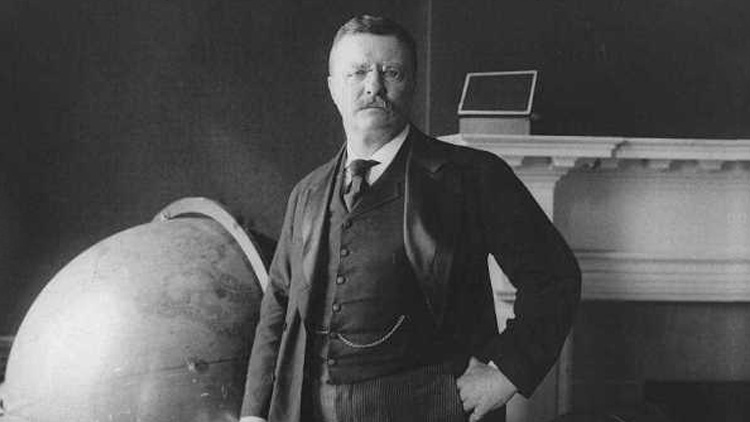

In the fading twilight at Sagamore Hill, a century suddenly seemed to slip away as a stout gray figure in a tweed overcoat wearing pince-nez glasses and a curving mustache emerged from the stately residence and stood on the walkway for a moment. Then the front door opened again, and a Park Ranger came out and shook hands with the man who uncannily resembled Theodore Roosevelt.

It wasn’t him, of course; he was an actor. Roosevelt died on Jan. 6, 1919, and more importantly the setting for this recent event, “Christmas with the Roosevelts,” didn’t exist when he was alive. Old Orchard, the Georgian-style mansion that’s now a museum, was built in 1938 by Ted Roosevelt Jr. and his wife Eleanor Alexander in an apple orchard hundreds of yards away from the main house for which the National Historic Site in Oyster Bay is named.

James Foote, a former Long Island machinist who has been embodying T.R. since 1979, appreciated the momentary confusion he’d recently caused this observer.

“I still got it!” laughs the 65-year-old. But call him “a re-enactor,” Foote insists, because “an impersonator sounds like someone who forges checks!”

Foote had kept his mustache when he got out of the Navy, but only after he started wearing glasses did people remark that he resembled the 26th president. He went to a costume party as Roosevelt and then was invited to be part of a Memorial Day parade in Sea Cliff, where he grew up. Next came requests for repeat performances, which required further research.

“I made a conscious decision that I better learn something about this fellow!” says Foote. “Once you start reading up on Roosevelt, you become infatuated with him. As historians say, it’s like being bitten by the Colonel!”

Over the years he’s appeared on Stephen Colbert’s show and the History Channel. Asked how long he’ll continue his portrayal, Foote slipped into character and, in Roosevelt’s characteristic high-pitched voice, said, “I wish not to cling to the fringes of departing glory!”

“There are a lot of people out there who think they have met T.R. personally,” says Amy Verone with a smile. For 23 years she’s been the curator at Sagamore Hill. She knows that apart from mistaking James Foote for the man himself, this is the closest many will ever come to experiencing the life Roosevelt led.

From 1902 to 1908, Sagamore Hill served as his summer White House. It was in T.R.’s library on the first floor where he brought the envoys of warring Russia and Japan face to face, and from that encounter came a conference in New Hampshire that produced a treaty in 1905, earning Roosevelt the Nobel Peace Prize a year later.

“We probably have 90 to 95 percent of the original furnishings,” says Verone. “When visitors come here, they see the house as Roosevelt had it… That’s a huge point in our favor in terms of our being able to connect the public to the life that the Roosevelts lived here.”

T.R.’s connection to the area started when he was 15 and his father brought him and his siblings to Oyster Bay for their summers. “We children, of course, loved the country beyond anything,” T.R. later wrote. “We were always wildly eager to get to the country when spring came, and very sad when in the late fall the family moved back to town.”

In Oyster Bay T.R. first met Edith Carow, his “little Edie,” as he called her, who would later become his second wife.

But it was with his first fiancée Alice Hathaway Lee that T.R. had purchased the 155-acre property on Cove Neck in 1880 (he’d later sell off 60 acres to relatives). Then he had architectural plans drawn up. Tragically, on the same day in 1884, both T.R.’s mother and his new wife died—and she had just given birth to their daughter Alice. As T.R. wrote in his diary, “The light has gone out of my life.”

For the next two years, T.R. was about as far away from Oyster Bay as he could get, becoming a cattle rancher in the Dakota Territory. Disaster struck in the winter of 1886-1887, almost wiping out his entire herd. But he came back east with an appreciation of wilderness conservation and an enthusiasm for the cowboy life. With the former he was inspired to lay the groundwork for the National Park Service; with the latter he formed a cavalry unit known as the Rough Riders, which achieved national recognition during the Spanish-American War when he helped lead them to victory up San Juan Hill in Cuba.

(Photo courtesy National Park Service)

Unprecedented President

He’d come a long way from being the youngest member ever elected to the Assembly when he was 23—and only 5-foot-8 and 135 pounds—according to biographer Paul Grondahl in I Rose Like a Rocket: The Political Education of Theodore Roosevelt. In fact, Grondahl writes, T.R. was then so scrawny that a Tammany Hall enforcer named “Big John” McManus, a former heavyweight boxer, planned to haze the young Republican in public. But T.R. heard about it and angrily confronted him in the corridor outside the Assembly chamber, shouting, “McManus, I hear you are going to toss me in a blanket. By God! If you try anything like that, I’ll kick you, I’ll bite you, I’ll kick you in the balls.”

Needless to say, the big bully was cowed by the young bull. And the political world began to take notice of the man who would become NYPD commissioner, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, and governor of New York, and one day lead a nation to greatness and set the standard for progressive Republican politics that has rarely been equaled.

“The vast individual and corporate fortunes, the vast combinations of capital which have marked the development of our industrial system, create new conditions and necessitate a change from the old attitude of the State and the nation toward property,” the then-Vice President Roosevelt said at the Minnesota State Fair in the summer of 1901. “More and more it is evident that the State, and if necessary the nation, has got to possess the right of supervision and control as regards the great corporations which are its creatures.”

Later that year, while hiking Mount Marcy, the highest peak in the Adirondacks, T.R. learned that President William McKinley had been assassinated in Buffalo. A little more than a decade afterward, while campaigning in Milwaukee against his former vice president William Howard Taft, who had the Republican line, and Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic candidate, T.R. himself was shot in the chest, yet the bullet had been slowed by a folded speech and a metal eyeglasses case in his inside pocket.

“Friends, I shall ask you to be as quiet as possible,” continued Roosevelt. “I don’t know whether you fully understand that I’ve just been shot. But it takes more than that to kill a bull moose!” He spoke for an hour and a half. The bullet was never removed.

“If he were in the Republican Party today, he’d have to be in the liberal wing,” says Brother Lawrence Syriac, a revered social studies teacher at Chaminade High School and current chairman of the Friends of Sagamore Hill, a nonprofit group of volunteers dedicated to preserving T.R.’s legacy, which sponsored the recent holiday event after federal budget cuts curtailed the Park Service’s involvement. Because of the 2013 sequester, Sagamore Hill held no Memorial Day or July 4th commemorative ceremonies.

For more than half a century, Syriac has been teaching American history, and he ranks T.R. right under George Washington and Abraham Lincoln.

“He seemed to know what was going on in the world,” Syriac says. “He was also the president of many firsts.” Among T.R.’s achievements, he was the first president to fly in an airplane, to go on a submarine, and to leave the U.S. while still in office and visit the Panama Canal.

And he was the first president to entertain a black man in the White House. As Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer Edmund Morris described it, Roosevelt had had “a momentary qualm” but his “hesitancy made him ashamed of himself, and all the more determined to break more than a century of precedent.” And it seemed to Roosevelt “so natural and so proper,” as T.R. himself later put it, to have Booker T. Washington at his dining table on Oct.16, 1901.

But the social occasion raised a national uproar, especially down South—it didn’t matter to southerners that T.R.’s mother was from Georgia and that his uncles on her side of the family had fought for the Confederacy. He was condemned in the press, but he didn’t care. T.R. was morally convinced that “my action was absolutely proper.” Indeed, he’d already hosted African Americans at his governor’s mansion in Albany and his home at Sagamore Hill.

An ardent adventurer, T.R. continued to pioneer after he was president. An uncharted river that he mapped in the Amazon rain forest still bears his name: Rio Teodoro. His wife Edith had stern words for Kermit, who was to accompany his dad in 1914. “Apparently, one of the last things his mother said to him was: ‘Bring your father back!’” says Verone. And the son nearly failed when T.R. was wracked with a leg infection and severe fever.

Homeward Bound

Roosevelt had intended to call his Oyster Bay estate “Leeholm” to honor his first wife, but once he was going to remarry, he picked Sagamore Hill after Sagamore Mohannis, a local 17th Century Native American chief who “had signed away his rights to the land,” as T.R. wrote. Starting in the spring of 1887, he and Edith made it their home—except when duty or curiosity called him away. Three of their six children, Theodore Jr., Kermit and Ethel, were born there.

“He was here to spend time with family and friends,” says Verone. “He spent his days hitting tennis balls with the kids, going rowing on the bay with Mrs. Roosevelt, hiking in the woods…”

In a letter to his daughter, Ethel, in 1906, Roosevelt wrote that “…fond as I am of the White House, and though I much appreciated my years in it, there isn’t any place in the world like home—like Sagamore Hill…where things are our own…”

Since 2012, the 23-room Queen Anne-styled mansion at Sagamore Hill has been closed to the public while undergoing a $7.2 million rehabilitation slated for completion in 2015. According to Park officials, the work is on schedule.

“I wonder if you will ever know how I love Sagamore Hill,” he told his wife as he lay ill on Jan. 5, 1919. He’d been suffering from severe bouts of rheumatism and malaria. About 4 a.m. she had gotten up to check on him. Newspapers soon reported what she found: “Colonel Theodore Roosevelt died in his sleep.”

T.R. was only 60 years old. Edith outlived him another 29 years. They share a grave in Youngs Memorial Cemetery, at the top of a little hill overlooking Oyster Bay. Their burial place is reached by 26 stone steps, in honor of his being the 26th president.

Only a mile separates T.R.’s favorite spot on the planet when he was alive from where his remains were finally laid to rest. Years ago, his father had worried whether T.R. would ever overcome his debilitating asthma, warning his then-11-year-old son that “you have the mind, but you have not the body. You must make your body.” Certainly, all that T.R. subsequently accomplished in his life showed that he took his father’s words to heart.

“Only those are fit to live who do not fear to die,” T.R. wrote, “and none are fit to die who have shrunk from the joy of life and the duty of life. Both life and death are part of the same great adventure.”

It’s fitting that on Long Island, he did both.