Sharing a vodka bottle of “holy water” while mourning their friend who they say froze to death, six homeless people in the Hicksville train station waiting room ponder their fate on a recent snowy Saturday.

One, a Syosset native who thinks a warm jail may be better than calling the so-called hotbox his living room, openly considers suicide before his fellow “skids,” as they prefer to be called, shout him down. The oldest among them, a 71-year-old ex-plumber named Irving, who says he’s been homeless 25 years, jokes about being murdered. The grim talk turns to the average life expectancy for those living on the streets, which is between 42 and 52—decades younger than most Americans.

“Why ain’t I dead yet?” a member of the group jokingly asks the others, most of whom are middle-aged. Playing off their morbid, self-deprecating sense of humor hardened by years of being treated like trash, another replies: “Because only the good die young!”

They all share a laugh, forgetting their misery, if only for the moment. Dim florescent lighting, faded-yellow brick walls and urine-scented metal benches are the only other respite from gray skies, subzero wind chills and the frozen ground outside. They may not have much, but they’ve got each other.

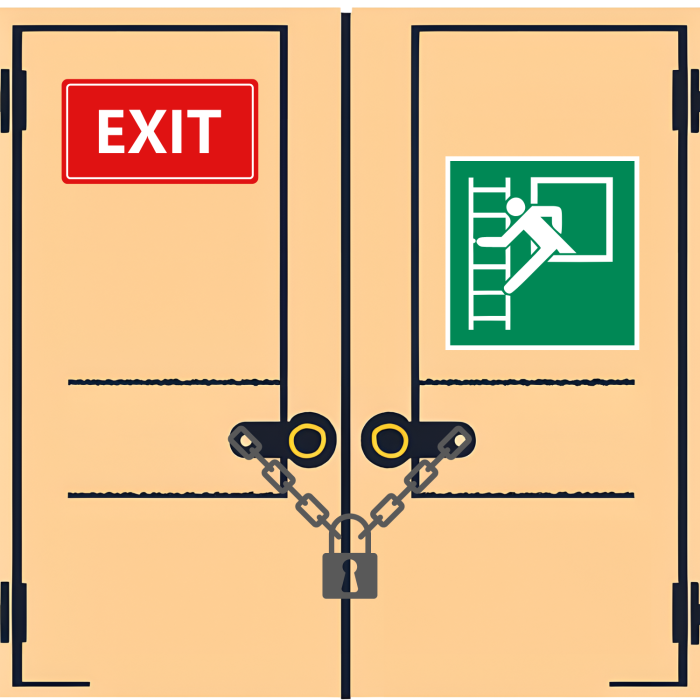

“Queen Maria,” as the five homeless men who protect her from being raped a third time call her, sits in a blue plastic shopping cart to keep raised the ankle she sprained after slipping on the ice. The group makes up just six of likely hundreds of undercounted, unsheltered homeless who refuse to stay in one of the more than roughly 100 shelters on Long Island despite the threat of frostbite, hypothermia and gangs.

“If you tell them you’re safer on the street, they look at you like you have three heads,” says Maria, a 41-year-old mother of two whose husband kicked her out when her drinking got out of control six years ago. “After a while you get used to this lifestyle and you learn survival skills.”

With the recent loss of their friend, “Mineola Tommy,” who they say was a Korean War veteran, the group is fully aware of the risk their “lifestyle” poses. Especially during a string of rare, extra-cold arctic blasts that led the Long Island Rail Road to keep the waiting rooms open 24 hours for a change.

“Most important right now is to stay warm,” says Bobby Angell, a 56-year-old former MTA worker who’s been homeless on and off for two decades since losing his job and family to crack. “This is killer weather.”

Local news outlets have reported the recent deaths of Tommy, another homeless man in East Meadow called “Wild Bill,” and an unidentified man in Medford, but confirming their cause of death—exposure or otherwise—with Nassau or Suffolk medical examiners is impossible without their full names and the consent of their likely estranged family. Tommy, the vet, wasn’t claimed right away at the morgue, an LIRR spokesman says.

The population of people who are homeless on LI is by estimates up 18 percent in the five years following the 2008 Wall Street crash that caused the Great Recession—from 2,639 in ’09 to 3,123 last year, the latter nearly the population of Southampton village—according to latest annual homeless surveys, which a Press analysis found are lower than reality. The rise has caused tension in Nassau, where residents worry about aggressive panhandlers, and in Suffolk, where two new “mega-shelters” galvanized their neighbors to protest against the unwelcome additions to their community. Attempts to address the issue have had mixed results.

LI’s rise comes as total homelessness fell 7 percent to 610,000 nationally last year with a 23 percent decrease in unsheltered homeless people (those not in shelters, living on the streets) since 2007, according to the U.S. Department of Housing an Urban Development (HUD), which counted more than one-third of those as unsheltered.

Although homelessness on LI was down seven percent as the stats show that growth reversed from ’12 to last year, New York State bucked the nation’s downward trend with the largest increase in homelessness—11 percent—from ’12 to ’13 with 7,864 people and a 23 percent hike since ’07, according to HUD’s 2013 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress.

Leading causes are still mental illness and substance abuse, with an increasing amount of aid emphasized for a subset of these sufferers, LI’s homeless veterans. Others who lost their homes in Sandy—both directly from storm damage or during its ensuing housing crunch—are still struggling, too, although it’s unclear how many of the 17 superstorm survivors the federal government was reimbursing for staying in hotels in New York as of December are from LI. Smaller subsets include people with HIV/AIDS, victims of domestic violence and runaway children.

Homeless people may remain largely invisible—aside from the occasional panhandler or garbage picker—but more are teetering on the edge of joining their ranks, experts warn.

“Working people are one check away from being homeless,” says Johnola Morales, managing director of the Hempstead-based Interfaith Nutrition Network, which has seen more clients at their soup kitchens across LI and three shelters in Nassau. “It would take a very small emergency for people to not pay their rent and wind up in the same situation.”

THE FORGOTTEN

Footprints in a foot of snow lead up to a graffiti-covered abandoned house in Wyandanch. Following them with a flashlight before dawn last month, Greta Guarton peers into a busted-out window and shouts: “Hello?”

A voice from behind an upstairs window blocked by junk yells back, asking what she wants. After a back-and-forth, she gets what she’s after: information. The man tells her that he spends time at the train station, has been on the streets for two years and isn’t alone—three others are in the boarded-up house, too.

Guarton, executive director of the Long Island Coalition for the Homeless, makes such vacant house calls for HUD’s Homeless Point-in-Time Count, held one day each January, a census of those in shelters and on the street. She coordinates volunteers who count the unsheltered. The local tally is then rolled into national stats to be released later this year.

In the broken window, she leaves four donated sweatshirts and paperwork with phone numbers for social service agencies that those inside can call. Then she trudges back through the freshly fallen flakes to her SUV.

It’s more productive than when she follows tracks in the snow up to two other nearby vacant homes. No one answers at the second. At the third, she calls out in Spanish—she’s met undocumented immigrants staying there before—but again, there’s no answer, which she suspects is because they’re afraid she’s law enforcement looking to deport them.

“We heard people in a lot of [vacant] houses that wouldn’t come out,” says Guarton, recalling surveys going back a decade. “They’re terrified to talk to us.

“If they don’t have documents of being here legally, they’re not eligible for most services, including emergency housing,” she adds.

Monica Diez, administrative director at the Workplace Project, a Hempstead-based nonprofit immigrant advocacy group, says many of those she works with avoid the shelters.

“Shelter-wise, they’re basically left on their own to fend for themselves,” Diez says. “They don’t know exactly where they stand with the immigration issue with sheltering and who’s eligible at least for a night, so they don’t really go through that resource.”

Complicating the survey further is that everyone tends to look homeless bundled up in the dead of winter. Guarton stops a man on the street, then another, to ask if they know where the homeless are. One points to a vacant house she checked where nobody answered.

She heads to a bodega where the homeless are said to congregate. A group of men eating breakfast inside point her to another bodega across the street, where a man in a camouflage jacket leaves upon hearing Guarton’s query. The rest claim ignorance.

After sun-up an hour later, Guarton’s questioned more than a dozen around the downtown and only found the one vacant house dweller with three apparent friends. Other volunteers take over the search for the area after she leaves.

“There are tons of people who are obviously homeless and they say, ‘No, I’m not homeless, but I know where they are,’” Guarton says, noting that she can’t count those who appear to be, but deny being homeless.

Nassau, Suffolk and the shelter operators send her their stats tallying how many homeless are staying in emergency and transitional housing while she relies on volunteers to count those on the streets all day and night for the survey. But the margin of error for polling such a transient group is incalculable. For one, “The Hicksville Crew,” as the sextet at the train station call themselves, say they weren’t counted.

Guarton expects the stats for LI’s unsheltered to be lower than reality. Especially since only about 50 volunteers—half of those last year—were available when the survey came the day after an average of 14.5 inches of snow covered parts of LI. Shelters may serve more clients on such snowy nights, which compensates for some of the unsheltered that could be missed, but there are many more homeless that aren’t counted at all, such as those temporarily in jail, rehab and psychiatric wards.

Statistics for how many homeless are jailed, committed or in rehab were not available.

Suburban sprawl also makes the homeless census harder than in New York City, where counters scour the metropolis in grids. Volunteers on the Island mostly target known homeless hangouts for their leg of the national survey—but those living in cars, for example, tend to go uncounted, advocates say. Volunteers counted 207 unsheltered in ’09—8 percent of LI’s homeless that year—and less than 100 every year since, except last year, when 117 were tallied. Results of this year’s street count were not available as of press time.

“I think it’s a useful exercise, but I would have questions about its absolute accuracy,” says Joel Blau, professor of social policy at the School of Social Welfare at Stony Brook University. He likens the homeless stats to the unemployment rate, which is estimated to be twice as high as reported since it doesn’t count those whose benefits ran out.

“The problem with that is homeless people often try to be elusive,” he says. “You never know if you missed the person under the bridge, or whether somebody’s in the basement of the abandoned house or whether they’re in the woods at the end of a dead-end street.”

SKID ROW

In the easier-to-count segment of the homeless population, Suffolk officials report a more than 62-percent increase in individuals seeking temporary housing assistance over the past five years—from 1,405 in ’09 to 2,260, about the population of Shelter Island, last year.

That includes a 30-percent increase since May in homeless families—totaling 535—consisting of 684 adults and 1,282 children, as of December. To meet demand, the county last year contracted two new family shelters, each fitting nearly 100 families, in converted hotels two miles apart from one another in Hauppauge and Brentwood. Neighboring school officials have complained that the added homeless children overwhelm classrooms; outraged neighbors say the mega-shelters ruin their communities and the facilities’ legality has been debated in the county legislature.

And there’s still not enough shelters, advocates and officials say.

“The wintertime is the time when demand for homelessness goes up,” Suffolk Social Services Commissioner John O’Neill told the legislature’s human services committee in December while being pressured to cut the number of families at the two controversial shelters. “I’m not going to commit to shifting families out of some place that I may need to place homeless families.”

Legis. John Kennedy Jr. (R-Nesconset), the legislature’s Republican minority leader, had proposed a bill that would cancel the contract with the new shelters, but the measure was tabled. He maintains the county should abide by its law limiting shelter size to 12 families, but the county attorney says state law trumps county limits on shelter sizes in these cases.

“There are many, many, many shelters throughout Suffolk County, but only three of them that go to this size and really nothing that eclipses this facility in the center of Hauppauge,” Kennedy said at the same meeting. “So right there we go to what is clearly an equity issue.”

Dozens of residents, arguing they’ve absorbed more homeless than other communities, packed the meeting to sound off in support of the bill, and are expected to do the same when the legislature holds its first full meeting of the year this month.

“What Suffolk County wants to do to the Hauppauge community is an outright disgrace,” Joanne Garramone, a longtime resident of the area, told the panel. “Concentrating all the homeless into our community…to save money for the county will in the long run severely hurt our residents’ safety, finances, taxes and value of their home.”

Legis. Kate Browning (WF-Shirley) said at the same meeting that she received some “disturbing” emails with comments “derogatory” toward homeless families after she previously said that the anti-mega-shelter crowd are arging NIMBY—not-in-my-backyard.

Aside from the size and school aspects of the issue—officials say many of the children in shelters are bused to their hometown schools—some mega-shelter opponents’ comments suggest the fear is that all homeless are alcoholics or drug abusers, like the Hicksville Crew. That isn’t necessarily the case.

“A large portion of our homeless are the result of a slow-recovering economy coupled with the high number of bank foreclosures on Long Island,” says John Nieves, spokesman for the Suffolk Department of Social Services (DSS). “Another contributing factor is the high cost of living on Long Island.”

While the federal government defines poverty for a family of four as a total income of $24,343 a year, the poverty level for LI is $46,000 a year, due to the higher cost of living, according to the Long Island Federation of Labor.

And since much of the county’s homeless population and shelters are in western Suffolk, the safety net has holes on the ritzier East End. DSS officials say they’re planning to open more shelters around the Twin Forks, but it’s doubtful any new beds will open up before spring.

“We cannot take everyone who comes walking through the door, we don’t have the capacity,” says Tracey Lutz, executive director of Maureen’s Haven, a network of 18 houses of worship that host up to 60 homeless nightly more than 100 times annually. “The system that we have in place right now doesn’t work, particularly on Long Island for long-term solutions… We have to give people opportunities to earn a living wage.”

She also takes issue with DSS requiring eviction notices for clients to qualify for their shelters.

“This is particularly concerning because many of the people that are looking for shelter have not lived in a traditional environment where they would easily have access to an eviction notice,” she says. “There doesn’t seem to be any wiggle room.”

Nieves says DSS will except informal eviction notices as proof of homelessness, or conduct evaluations to corroborate an applicant in fact has no place to go.

GIMME SHELTER

Asked how many homeless people Nassau sheltered in recent years, Dr. John Imhoff, the social services commissioner for that county, provided stats for how many homeless people his agency placed in permanent housing and got out of motels.

LI’s homeless coalition reports a 42-percent hike in sheltered people in the county from ’09 to ’12—595 to 847, about the population of Quioque. Survey results broken down by county were only available for that four-year span. Starting last year, LI’s homeless stats are lumped together.

Imhoff says he has no plans to open any mega-shelters in Nassau, but he didn’t need to for sentiment rivaling that of Suffolk’s mega-shelter neighbors to rear its head in East Meadow, home to Eisenhower Park, historically a hotspot for the homeless. That is, until last year, when Nassau police, tired of summonsing homeless people that ignore the tickets, stepped up arresting them for quality-of-life crimes. Especially after finding out that some had obtained keys to the bathrooms, where they made themselves at home.

“They’ve made it very unpleasant for people who sign up to use the barbeque areas,” Third Precinct Inspector Sean McCarthy told an East Meadow community meeting last spring. “We’ve made it less hospitable for them in Eisenhower Park. That’s a ship that doesn’t turn around right away. But, instead of writing appearance tickets at the scene, we usually bring them into the precinct and process them in a regular arrest fashion, not just write them a ticket that they’re never gonna answer anyway.”

McCarthy was not available to provide an update on how this tactic has fared. A large homeless tent city tucked in the woods just west of the park that authorities shut down following a murder there a decade ago had one tent on a recent visit. Another camp along the Meadowbrook State Parkway, farther south near a Freeport day laborer hiring site, has seen two men living in those woods die in as many years, including a Hispanic man in his 20s found dead there last May.

“He lived over there all winter,” Fernando, who declined to give his last name, told the Press following the March 2012 death of 33-year-old Jose Garrido-Lobo, a father of four who they nicknamed “El Cantante,” Spanish for “The Singer,” because he would sing when he drank. “He’s a good guy.”

As for the progress on solving the overall problem of homelessness in the county, Imhoff touts reducing the number of families in motels from 44 to 16 in the past three years and 142 to 112 in shelters for the same time span. He also says the county found homes for 328 people in ‘12 and 629 last year.

“I don’t think the economic conditions for many families have changed that radically, but I think that our aggressive policy of working with our housing specialists and helping families acquire the means and support to get out of shelters and motels [is] beginning to see a difference,” Imhoff says.

Rev. Daphne Haynes, president of nonprofit Peace Valley Haven, which operates a men’s shelter in Roosevelt and does outreach to the unsheltered, says she’s noticed fewer people on the streets, but convincing the chronically homeless to seek help is still an uphill battle.

“‘If I’m going to die, I’m going to die right here,’” one homeless person told Haynes, she says. “If every person was accepting, I could bring in…20 people a night. We can’t turn our eyes and say the need is not there.”

Blau, the Stony Brook professor, notes that Nassau’s homeless arrest policy is likely to be as ineffective as Suffolk’s mega-shelters—he favors smaller facilities—but notes that the issue needs a fresh look from local leaders.

“We have to figure our some way of addressing this so we don’t come to accept the fact that when you go to a local supermarket some guy’s gonna be outside collecting cans and possibly begging,” he says. “Thirty or 40 years ago it was shocking to see people in the street, and I think what’s happened is we got used to it and not only have we gotten used to it, but we’ve gotten used to it in the suburbs, which was supposed to be immune to the city’s problems.”

STAND YOUR GROUND

Aside from warmer weather on the horizon, silver linings are seen in new alliances formed to help tackle homelessness on LI, including veterans groups and the LIRR partnering with advocates.

Railroad workers have begun sharing information on where the homeless are staying with the LI homeless coalition, says Guarton, the group’s director, who adds that Services for the Underserved, a large New York City-based homeless veterans group, set up an LI outpost in Farmingdale for the first time last year.

“We thought it was time to expand our operation,” says Brett Morash, a retired U.S. Navy veteran who’s director of veterans’ services at the nonprofit, which partnered with several LI vets groups’ goal of helping 500 families. “The idea of the program is to prevent veterans from becoming homeless.”

Guarton is as thankful for the reinforcements on the veteran front as she is for backup from the LIRR, where advocates say an average of half dozen homeless of all types are often found in waiting rooms, sometimes twice that.

“This joint effort was prompted by a noticeable uptick in complaints about the homeless from our customers as we increased the hours of waiting room availability at many LIRR stations,” Salvatore Arena, an LIRR spokesman, tells the Press. “We are also working closely with the MTA Police on this issue.”

For those homeless folks that take the advocates up on the offer to stay in one of their shelters, their odds increase for getting back on their feet with the help of social services. The mega-shelters offer even more programs because of their size, Suffolk officials say.

“As long as there is life, there is hope,” says Haynes, of Peace Valley Haven.

There’s another saying common in this line of work, too, repeated by Lutz at Maureen’s Haven: “There, but for the grace of God, go any of us.”

Back at the Hicksville train station, Angell recalls making $40 hourly as a track worker. Now he’s lucky if he makes $40 a day recycling cans. Between swigs from a can of cheap beer, he says, “I wish I knew then what I know now.”

-With additional reporting by Samuel J. Paul

Important Numbers:

- Suffolk County Department of Social Services Central Housing Unit hotline: 631- 854-9517 between 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., Monday through Friday. For emergencies during non-business hours, weekends and holidays, call 631-854-9100.

- Nassau County Warm Bed Homeless Hotline: 1-866-927-6233

- Nassau Homeless Help Line: 516-572-2711

- Nassau Department of Social Services: 516-227-8395. After hours: 516-572-3143

- Long Island Crisis Counseling & Referral Center: 516-679-1111

- Nassau County Coalition Against Domestic Violence: 516-542-0404