“Hello, Gorgeous!”

Those were the first words spoken by Barbra Streisand in Funny Girl, a sanitized Hollywood musical about the vaudeville star and Broadway comedienne Fanny Brice. The lavish greeting could equally apply to the big summer house overlooking Huntington Bay that Brice owned from 1919 until 1946.

One of the most famous performers in Ziegfeld Follies’ talented roster—along with W.C. Fields, Eddie Cantor, Billie Burke and Will Rogers, to name a few—Brice had a flare for the dramatic, on stage and off. At her Bay Avenue place in Halesite, she remodeled the front stairs, widening the bottom landing a few feet in the foyer so she could make a dramatic entrance to welcome her many guests and admirers.

As Brice herself said, possibly in jest, “I’m a bad woman but I’m damn good company!”

A posthumous winner of a Grammy, Brice never won an Oscar, although she did do movies as well as theatre and radio shows. For her many accomplishments, her star shines on Hollywood Boulevard’s Walk of Fame. Funny Girl was Streisand’s first film and it won her the Academy Award for Best Actress in 1968—although she had to share the prize with Katherine Hepburn, who’d starred in The Lion in Winter. The 86th Academy Awards ceremony is broadcast on March 2 this year. Although no musical is up for an Oscar—nor is Streisand a nominee—it is a fitting time to pay tribute to an entertainer born Fania Borach in New York’s Lower East Side, whose life links Huntington to Hollywood.

Today Brice’s Bay Avenue property is lovingly preserved by Lynn and George Pezold. They bought it in 1982, not because the home had belonged to Brice but because they had been to a party there, and when the house came on the market a year later, they knew they wanted it. In fact, they didn’t know about Brice’s connection until afterwards.

“We’ve learned so much!” says Lynn Pezold with a laugh, as she leans forward conspiratorially at the kitchen table, sharing anecdotes and coffee recently with visitors.

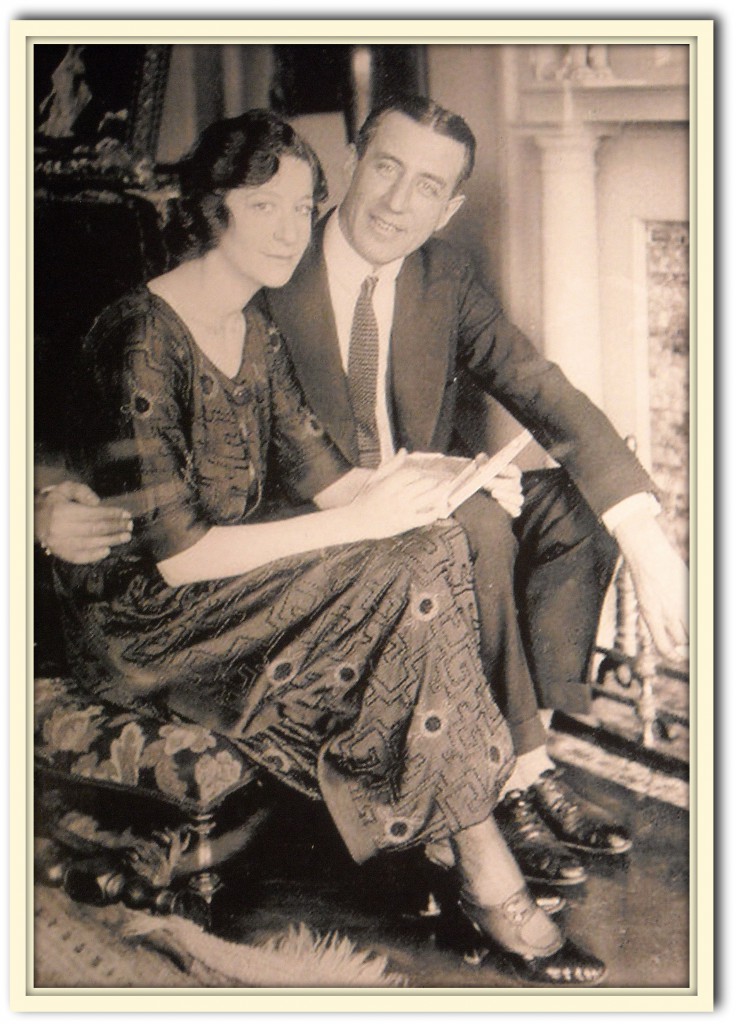

Upon occasion, they put Brice’s portrait on their piano in the living room along with sheet music from one of her popular songs, like “Second Hand Rose,” on the music stand. The Pezolds had to replace the main beam because the first floor had buckled under the weight of the expanded staircase—not to mention the toll the termites had taken. The original owner, John L. Doughty, had built the main house in 1897 and added a kitchen in 1902. The Allard family bought it in 1911 and sold it to a fellow named Jules W. Arnold in 1919. That name was one of the aliases used by Nick Arnstein, Fanny Brice’s notorious gangster husband, who was a far shadier character than the way he’s played in Funny Girl by the suave Omar Sharif, who’d starred on the big screen in Lawrence of Arabia and Dr. Zhivago.

“That house was the only thing Nick ever bought,” said Brice much later. “He made some money gambling and paid $14,000 for it. I paid $25,000 to have it remodeled.”

“She added all sorts of ‘modern things’ to the house,” says Pezold. Brice added a wrap-around porch, expanded the back of the house with a big family room with a view of the harbor, as well as installing French doors throughout the downstairs to make it brighter, and enlarging the living room and the parlor space so they flow together better—perfect for big parties.

But what Brice didn’t do was insulate her summer house, admitted Pezold with a feigned shiver. After Brice had sold the place and permanently moved to Los Angeles, where she died in 1951, a steam riser from the boiler in the basement was added to supply heat to the radiators upstairs, but unfortunately it thrusts right up through the vestibule by the front staircase that Brice loved so much.

The house in Funny Girl got the Hollywood treatment—portraying her Huntington digs as more of an opulent mansion than it really is.

“To tell you the honest truth, I don’t think anything would have made Fanny happier [than seeing it that way],” says Lynn Pezold. “She was not afraid to get a nose job after she’d been a star of the Follies.”

Love is blind

As for the passionate relationship at the center of Funny Girl, both the film and the original Broadway musical that had also starred Streisand deviated significantly from the real story—no doubt due to the fact that Arnstein was still alive during its development and itching to sue.

When Brice first met Arnstein, he was still married—she found out later. His divorce only came through two months before their daughter Frances was born at their new Huntington home in 1919, according to Brice biographer, Herbert G. Goldman. Arnstein was part of a gang of swindlers that stole $5 million worth of Wall Street bonds in 1920 and he was wanted by the police. He’d already done time in Sing Sing for wiretapping fraud and so he went on the lam, forcing Brice to give birth to their son William without him around. Their son later became a successful painter and art professor at the University of California at Los Angeles, and was never mentioned in the movie by mutual consent with the film’s producer Ray Stark, his older sister’s husband.

Brice worked feverishly and shelled out money constantly to pay for her husband’s mounting legal bills, but the law finally caught up with him. Arnstein spent almost two years in federal prison at Leavenworth, still claiming his innocence. In her revealing rendition of the song, “My Man,” which was a show-stopper both for Fanny Brice at the Follies in 1921 and Barbra Streisand on the silver screen decades later, she would sing, “But whatever my man is, I am his—forever.”

One story that Pezold has heard since they’ve owned the Halesite home was about the time Brice decided to throw a surprise party for her husband. Through the French doors leading from the kitchen, Arnstein saw the guests arriving before they could see him. He took off down the hill, grabbed a cab on East Shore Road and took a train from Huntington into Manhattan. At another occasion, Brice was entertaining when a fire broke out in the attic—Pezold says the burnt embers can still be seen up there—but the hostess didn’t want the party to break up. She pretended that she had also invited the men from the Halesite Fire Department to attend, and made sure they stayed for food and drinks—after they’d put out the fire.

Her husband’s relationship with the department, however, was reportedly much rockier. Arnstein had set up a casino for the firemen’s fair one summer and, Pezold says, “Nicky bilked them out of $500,” so a wealthy neighbor had to chip in to cover the shortfall. She learned that story from the benefactor’s grandson. Recently Pezold heard from a local woman about an encounter her great aunt had had with Brice when she was working as a maid next door, where a school stands today. The maid and her friend had ventured into Brice’s apple orchard.

“They didn’t think anybody was home and suddenly the light came on, and Fanny came out on the porch, and said, ‘Who’s there?’ The girl said, ‘It’s just us and we’re stealing your apples!’ They had stuffed the apples in their bloomers—that’s how old the story is!” says Pezold. “And so Fanny just started laughing, and said, ‘There are more apples than I could ever eat. Enjoy!’”

What finally caused Fanny Brice to run out of patience after 15 years with Arnstein was when she found out he was having an affair with an older, wealthier woman. As she told Marjorie Dorman, a reporter for the Brooklyn Eagle in 1928, a year after her divorce, “I’m done with a home and I’m done with men.” But there were rumors to the contrary, the reporter persisted, mentioning Arnstein and the Broadway impresario Billy Rose.

“Talk about my being reconciled with Nicky is just bunk,” said Fanny Brice at the time. “No, I’m not going to marry Billy Rose or any other man. I’ll tell you what—if I ever saw a romance coming in my direction that looked dangerous, I’d run the other way.” And then she elaborated, Dorman wrote, “that showed her a bitter woman than one would have quite anticipated in view of her rattling line of comment, her devil-may-care attitude.” Brice told the reporter, “I don’t think any man can be happy with a woman who has a career.”

Unfortunately, Brice may have been right about the men she was with—although she held onto the house in Huntington and bought bigger ones in L.A., and she did, indeed marry Billy Rose in 1929, only to divorce him in 1938. But had she been born in a different time, she may have been proven wrong.

Funny, how it all works out sometimes—and how sometimes it doesn’t come close.