Twelve fifth-grade students gathered around a conference table at Long Island University at Post facing two flat screens on a rainy Monday morning. One screen reflected their own image, the other showed seven children about the same age, accompanied by their teacher and principal, in South Africa. They raised their hands excitedly, trying to wait their turns to talk, but there was so much to ask.

Among the queries that arose: “Do you have violence there?”

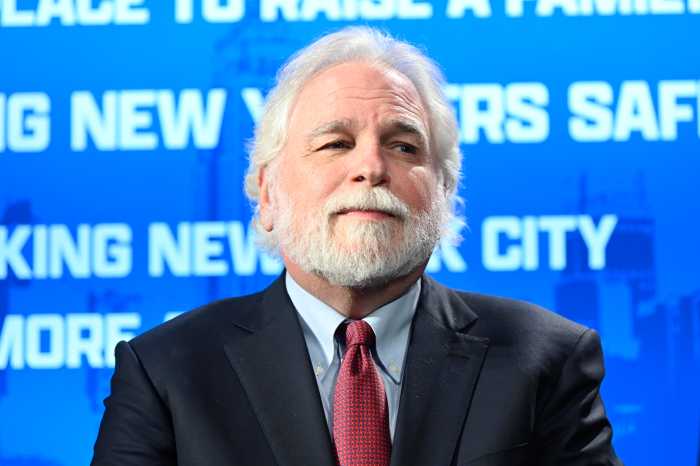

The dialogue, organized by Arnold Dodge, the chair of the Department of Educational Leadership and Administration at LIU-Post and John Singleton, principal of Clear Stream Avenue School in Valley Stream, was four years in the making. The idea is to get the children to discuss difficult social ideas and to recognize their significant similarities and in doing so, to dissolve their perceived differences. The children converse in real time about bullying, technology, music and the environment—satisfying their mutual curiosity of such vastly different cultures.

“The curriculum has been focused on human rights,” Natalie Nelson, a fifth-grade teacher at Clear Stream, told the Press while fighting back considerable emotion. “The students learned about Nelson Mandela, who died when Mr. Singleton was visiting there in December.”

To have the children actually speak to the students in South Africa, and to hear firsthand about apartheid, and to connect that with the segregation that these students experience, was incomparable, she said.

Starting in 2008, Dodge’s academic research led him to study the impact of poverty on schools in South Africa. He crosses the globe every fall to visit South African schools and to connect with educators there. This past December, Singleton joined him, where they met Berte Van Wyck, the Professor of Education Policy Studies at the University of Stellenbosch in South Africa and John Jacobs, the principal of the Marvin Park Primary School in Macassar, South Africa.

“It takes you out of your egocentricity,” Nelson said, adding that kids feel their problems are common not only among other children in the United States, but across the globe as well. She noted that the experience of seeing children speak to the universality of issues like bullying is of monumental importance.

There were some significant differences in the South African students’ day-to-day lives. One student spoke about how he had no running water in his house. Another had no electricity.

“Many times, it’s the students who don’t have that shed light on those who do,” said Singleton, noting how the children would have a new-found appreciation for what they’d considered “essentials.”

Valley Stream has undergone a big transformation, as it has become a “majority-minority” school, going from a 72-percent white student population in 1999 to 26-percent last year. Multilingual students from Clear Stream cross a diverse range of backgrounds. Similarly, the students of Marvin Park speak languages ranging from Afrikaan to French, Portuguese and English, among others.

Clear Stream Avenue fifth-grader Anthony Pimento found it helpful to get a peek into their culture.

“There’s a big difference,” he said, “because they have to share electricity.”

South African students asked if American students had to pay for public education, prompting a quick lesson from Dodge on the complicated nature of the system supported by property taxes. South African schools are divided into “quintiles,” where a school’s financial backing is determined by the relative wealth of the students who attend. Marvin Park is a quintile one school, which means that it is of the poorest ranking—and the government provides the education.

Singleton, showing pictures from his December trip to Marvin Park, pointed out the bars on the windows of the school designed to keep the students safe. He was curious to know if South African schools experience the school shooting phenomenon like American schools, but did not have time to ask. One of his students, however, broached the subject of the Nigerian girls who’d been kidnapped and asked how they kept themselves safe.

Before the meeting, the students each composed biographies to share among each other across different social media platforms, essentially forming modern-day pen pal relationships. Afterward, Justin Gomez, another fifth-grader from Clear Stream Avenue School who approached the student meeting formally in a suit and tie, said he was impressed with his South African counterparts.

“These kids are getting far with technology,” he said. “Technology brought us to the moon—and now this!”

Dodge sees this opportunity as a catalyst for future endeavors including his ultimate goal: an international institute where students can connect through thoughtful conversation, music, dance, and technology both here and in South Africa. He is waiting on several grant applications that might let him facilitate global connections that might just change the world.