Kristy Bower spotted her father from across the street and cried out.

“That’s my dad! That’s my dad!”

Before the car could completely stop, the 27-year-old bolted out the front passenger door and sprinted toward him, her makeup streaking from her eyes in a mix of teardrops and rain.

Ronald Bower, 53, had just taken his first steps outside prison walls in more than 23 years. He dropped an enormous fishnet laundry bag containing all of his worldly possessions and tried his best to hustle toward her, too, though a pair of sneakers a size or so too small dismantled his stride, turning it into more of a restrained, awkward hobble.

In the shadow of Clinton Correctional Facility’s brooding, 60-foot-high drab white concrete walls, surrounded by an intricately woven mesh of chain-link fences laced with spirals upon spirals of razor-sharp barbs, just after 8 a.m. on June 12, they embraced.

It was a meeting Kristy had been dreaming about since she was a little girl.

“I love you dad,” she wept.

“I love you, Kristy,” he cried, patting her on the back and rubbing her shoulders as he held her. “I love you so much. Everything’s gonna be alright.”

He kissed her on the side of her face.

This is how Ronald Bower spent his first precious few moments as a “free” man—sobbing uncontrollably, wrapped in the arms of his eldest daughter, professing his love for her.

The Long Island Press, which has been covering Ronald and his family’s plight for a decade, had exclusive access to this deeply emotional, long-sought reunion.

Actually, we picked him up.

The Queens father of two is a convicted Level 3 sex offender who an ever-growing number of law enforcement officials believe had absolutely nothing to do with the crimes for which he’s been serving an 18-to-54-year sentence because, for one significant reason, the pattern of sex attacks continued after his arrest and incarceration. He was released on parole following a letter to the Parole Board from Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman’s Assistant Attorney General and Conviction Review Bureau Chief Thomas Schellhammer, stating it “highly unlikely that Bower committed the crimes for which he was convicted.”

In his first interview as a free man, Bower emphatically maintained his innocence, grieved for the victims, thanked supporters and praised his family. He recalled in vivid detail the specific dates and events which led to his near-quarter-century behind bars, the unimaginable anguish and horrors he somehow survived on the inside and the sheer torture of his loved ones, who, along with his longtime attorney Jeremy Goldberg, appeals bureau chief of the Nassau Legal Aid Society, and a slew of law enforcement officials, have been doing everything in their power to get him home and, ultimately, clear his name.

Much of what he told the Press included the same horrific scenes he’s shared with us in countless letters and during several jailhouse interviews over the years, more so in the past three months: his arrest at his jobsite in 1991, a frantic call for help from a psychiatric hospital shortly afterward (sent there due to his inconsolable crying and quick descent into depression), the ominous foreboding that he would never see his mother, Margaret, who is in her 80s and disabled, alive again. Most of these nightmarish recollections and visions—and those which always cause him to erupt into the most emotional and dramatic outbursts—concern his two daughters: Kristy, who was just 4 years old when he was incarcerated, and Holly, who was just 2. He hasn’t seen his youngest in more than two decades and has yet to meet his two grandchildren.

Those moments are forever seared into his consciousness, and he retreated to these terrors repeatedly throughout a roughly three-hour interview with us in a hotel room in nearby Plattsburgh, N.Y. immediately following his release and continued on the seven-hour drive home.

Some of his other observations would sound comical if they weren’t born from such devastating tragedy: his astonishment and non-comprehension of cell phones (“Wow, everybody has those,” he remarked), motion-detectors, the price of a gallon of gasoline, and even “this little coffee shop called Starbuck, Starbucks or something like that, that everybody drinks now.

“I feel like I’ve been dead for the past 23 years,” he told us as we eventually sped through familiar neighborhoods, passing old landmarks he recognized, such as the New York World’s Fair Unisphere, and new ones he’d only dreamed about, like Citi Field, the latest home of his beloved Mets. “And now I’m alive and everything’s changed.”

Bower’s release came just in time for Father’s Day, and though his newfound “freedom” is cause for him and his family to rejoice, it’s a hollow, short-lived triumph, for in reality, he’s really just trading one set of shackles, forged of iron and steel, for another, made of ink.

His status as a violent sexual predator with the highest and most restrictive risk-level assessment mandates a lifelong set of rules requiring him to jump through flaming hoops just to stay out of prison and carries a stigma that can never be erased but for full exoneration. Bower needs housing, counseling, a job, medical treatment.

“I just got out of one prison,” he says sadly, “and into another.”

Long and Winding Road

Bower was arrested mid-shift at his job at the Douglaston Mall, where he worked as a security guard, on May 10, 1991, just three days after his 30th birthday. Investigators of the Queens Sex Crimes Squad originally picked him up following a tip from his estranged ex-father-in-law in response to a sketch of a suspect wanted for accosting two teenagers on a rooftop in Corona. That incident was later discovered to have never taken place, the victims having recanted, according to court documents. Bower was forced to replace his security uniform with a hooded sweatshirt that victims of a series of sex attacks in Nassau and Queens in the vicinity of Union Turnpike between 1990 and 1991 had reported their assailant as wearing, and then he was paraded through more than a dozen police lineups.

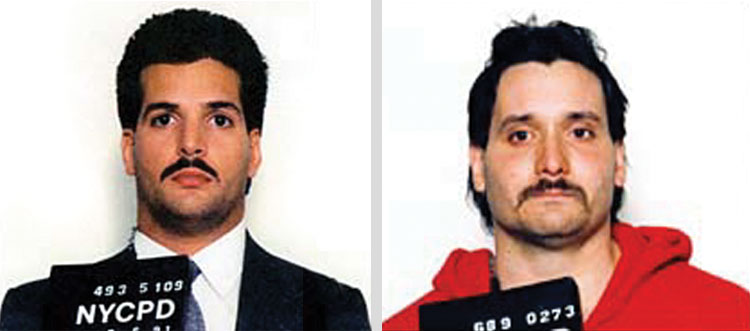

He was picked out for three such attacks—pattern crimes attributed to a perpetrator investigators dubbed “The Silver Gun Rapist,” who was responsible for possibly more than a dozen rapes and sodomies between 1990 and 1991 all involving the use of silver or black .38 revolvers. Bower was acquitted in one and convicted of two, in Queens and Nassau, on eyewitness testimony and that of a veteran criminal-turned-purported jailhouse informant, according to court papers.

The perpetrator’s M.O. was to abduct and accost women, sometimes two at a time, while they were walking or getting into their vehicles, and threaten to kill them unless they gave him oral sex.

Sometimes, he’d also rape them.

Despite Bower’s arrest and incarceration, and unbeknownst to him or his attorneys at the time, the pattern sex attacks continued, and three months after Bower’s arrest, another man with similar facial features as Bower was arrested and charged for two similar crimes: a New York City police officer named Michael Perez. Bower’s lawyers filed unsuccessful motions to vacate his convictions based on alleged procedural violations by prosecutors.

In one of those incidents, Perez was pulled over by police for driving the alleged victim’s car erratically and a loaded .38 was discovered under his seat, according to court documents, investigators and an Aug. 7, 1991 New York Times article titled “Police Say Officer Abducted and Raped Woman.”

Perez was acquitted in both those cases at trial, yet a subsequent investigation discovered that he was off-duty at the time of all the pattern attacks, owned a car, lived nearby many of the crime scenes, is left-handed (which matched victims’ descriptions of their attacker), and owned nearly a dozen firearms—including silver and black .38 revolvers—according to court filings and investigators familiar with both cases.

Following the jury trials, Perez was also placed under surveillance by the NYPD’s Internal Affairs Bureau. Based on their probe, he was brought up on departmental charges for patronizing a prostitute and lying about the incident at a departmental hearing, according to court records.

The woman he hired told police that Perez had paid her $14 for oral sex. Perez resigned from the force and avoided facing a trial over the charges, state the records.

Despite Bower’s mandated wardrobe change, Perez was allowed to switch into a suit and tie for his mug shot when he was originally arrested, according to a former senior investigator at the New York State Inspector General’s Office of the state Department of Corrections, who was the first to unearth discrepancies with Bower’s convictions and begin to compile a wealth of evidence pointing to Perez.

Bower did not own a weapon, or a car, and is right-handed, according to the investigator.

A substantial list of veteran law enforcement officials have come to Ron’s defense throughout the years. Among them: current or former members of the New York State Inspector’s Office of the state Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, the state Division of Criminal Justice Services, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and even members of the very sex crimes unit that originally arrested him. They believe Michael Perez, not Ronald Bower, is responsible for the crimes for which he is convicted, and demand Bower’s exoneration.

His parole, in fact, was possible in no small part due to the efforts of state Assistant Attorney General and Conviction Review Bureau Chief Thomas Schellhammer, who wrote a letter to the Parole Board at Clinton Correctional Facility on Dec. 30, 2013 calling for Bower’s immediate release, stating it “highly unlikely that Bower committed the crimes for which he was convicted.”

Schellhammer also explained his reasoning for recommending Bower’s release in his letter, citing an extensive, ongoing investigation into his case that included speaking with investigators and witnesses associated with the crimes for which Bower was convicted in an attempt to reconstruct those events.

“This position is based upon several factors,” writes Schellhammer, listing them in order: “a) His physical resemblance to another person who committed identical crimes at about the same time as these in question, some of which occurred after Bower was in custody; b) the possible mis-identification of Bower as the perpetrator of these crimes by the victims; c) the lack of a propensity or any other prior indicator that Bower was inclined to commit offenses of a sexual nature; and d) the probability that Bower had an alibi for the nights in question.”

Schellhammer’s letter set off a political shitstorm that eventually resulted in his replacement.

Both the offices of Queens District Attorney Richard A. Brown and Nassau County District Attorney Kathleen Rice, who’s currently running for Congress, blasted Schellhammer’s boss, Schneiderman, alleging they were clueless about the probe and blindsided. The AG’s office “vigorously dispute[d]” that charge, according to the New York Law Journal, yet eventually caved. All three agencies—the attorney general’s office and the Nassau and Queens DA’s offices—asked the Parole Board to “re-examine” its decision on Bower’s release.

Most recently, following an April discovery by the New York Post of an anti-Schneiderman Super PAC poised on spending millions to unseat the Democrat this November—and using Schellhammer’s support of Bower as a sledgehammer in that quest—the state’s top law enforcement official further backed away from Bower. His Chief Deputy Attorney General Harlan Levy formally withdrew Schellhammer’s statement of support. Last month, John Cahill, ex-Gov. George Pataki’s former chief of staff announced his run against Scheiderman.

In other words, Bower has become a radioactive political football, punted from one side of the aisle to the other, potential fodder for partisan attacks and smear campaigns, whether he’s innocent or not.

All this has not been completely lost on Bower, who for the last two months in prison spent much of his time consumed with anxiety over the possibility of his parole being revoked. Though, it’s hard to imagine him ever completely comprehending the sheer ferocity of the forces swirling around his predicament.

At one moment on the ride home, Bower suggested that Schneiderman’s Republican opponents might even be open to looking into his case and helping him get exonerated.

Bower, a stocky, muscular man with a bald head who repeatedly mocks himself as resembling “Curly from the Three Stooges,” stands in the bizarre, unique position of having an independent team of top law enforcement officials calling for his exoneration for nearly two decades while the state, at the urging of the two county prosecutors who represent the jurisdictions where he was prosecuted—Richard Brown and Kathleen Rice—label him the worst of the worst.

Breathing fast, his eyes red behind a pair of prison-issued glasses as we drove away from Clinton, nicknamed “New York’s Siberia” due to its remoteness just south of the Canadian border, the surrealism and severity of his reality combined in a cyclone of intense emotions, memories, grief, fear and joy.

“Dad, you look good, you look good,” his daughter told him, wiping away tears from his left cheek as we drove off.

“Oh it’s overwhelming,” Bower said after a deep breath, continuously blinking his bloodshot eyes and straining to hold back more tears. “It’s like my heart’s racing, I’m so happy to be with my oldest daughter Kristy. I’m so happy to be with you guys, I’m so happy to be out of that hellhole prison. I just want to get out now to be with my family, and be there for them and help out people.

“My oldest daughter’s been there for me 100-percent and she loves me 100-percent like I love her 100-percent,” he continued. “And it’s just so hard because I’ve been taken away from my family since May 10, 1991, and I didn’t completely do anything to anyone, and now I’m finally going home to my family. And I’m afraid to go anywhere by myself because I’m afraid they’re going to try to set me up again or put me back in the system and that’s why I want to make sure I have somebody with me wherever I go, because I’m paranoid that they’re going to put me behind bars again for something I didn’t do.

“And just to have people that love me and care for me, to come pick me up, it’s so wonderful.”

[Recently released inmates who aren’t picked up are given $40 and put on a bus to Plattsburgh—something that nearly happened with Bower, despite prison officials’ knowledge that his daughter would be there.]

He thanked his longtime attorney, Nassau Legal Aid Society Appeals Bureau Chief Jeremy Goldberg, as well as Goldberg’s late wife, Linda, whom Ronald was extremely close with, exchanging countless letters between each other throughout the years.

“I thank you from the bottom of my heart, 100-percent, for helping me all these years to try to clear my name,” he said.

“I love you Linda in heaven,” he cried, glancing up toward the sky, “I miss you so much.”

He thanked Schellhammer—expressing grief over the fact the state official had lost his job trying to right the horrible wrong Bower says has been done—and the other law enforcement officials who’ve supported him through the years, too.

Bower also grieved for the victims of the crimes for which he was charged and convicted.

“I didn’t do anything to any of you,” he pleaded, Kristy’s hand clutching his. “I took a polygraph test from the world’s best polygraph test expert [Dick Arther], and I passed, and I’m willing to take as many polygraph tests, additional polygraph tests, to continue to convince you that I didn’t do anything to anybody.

“I wanna get my name cleared so bad so these victims can know that I’m 100-percent innocent,” he continued. “And it’s just a tremendous nightmare. It’s horrible.

“But now this is so wonderful, I never felt so much better in my life,” he added, his eyes welling up again. “I think the best I felt in my life was when my daughters was born and this, this, this is probably next. It’s great.”

Kristy handed him a New York Mets baseball cap with the team’s mascot and told him he’d be going to a game for Father’s Day.

He never made it due to panic attacks.

Scarlet Letter

Our first stop was a hotel in Plattsburgh. He shuffled through the lobby as inconspicuously as possible while lugging his enormous mesh satchel containing two decades’ worth of correspondence, photos and holiday cards, along with a rigorous workout routine scrawled on a piece of cardboard, prison documents and several smelly T-shirts. When we got onto the elevator, Bower shared his fears that the handful of guests taking advantage of that morning’s complimentary continental breakfast knew he was a convict.

It was a fear he’d vocalize many more times later on, following a me all at a local restaurant recommended by the hotel’s front desk, called The Hungry Bear Restaurant—“it’s shaped like a log cabin,” she smiled—and as we made our trek south down State Route 3, I-87 and the New York State Thruway, occasionally stopping at rest stations along the way.

While Bower took a shower and changed into a black-and-white Beatles T-shirt (his favorite band), black workout pants and a new, aqua-blue-and-grey-fluorescent-orange laced pair of Pumas Kristy bought for him, she sat on the floor of the hotel room and sifted through the contents of his prison bag, separating them into piles.

“These need to be burned,” she said, pinching the edges of several solid-colored T-shirts and amassing a pile near the bathroom door. “They stink like cigarette smoke.”

Bower doesn’t smoke, but on several interviews with him inside he’d constantly complain that even though it’s not allowed inside prison, once the lights go out at night the entire facility fills with smoke, from inmates sneaking cigarettes into their cells. He explained again how he couldn’t vocalize this to prison management, because other inmates would find out who it was that ratted them out and seek retaliation.

So, his lungs endured a constant flow of second-hand smoke for more than two decades.

Rejoining us, Bower looked at the piles she’d made and somehow convinced her not to throw his shirts away, but to keep them so they could be washed and he could hold onto them for the “memories.”

Then, his mind turned to his mother Margaret and his brother Steve, who despite her old age and myriad health issues, sent along commissary money each month. They also prayed, relentlessly, his mother always begging for the same simple wish: “Rescue Ronnie home.”

For several minutes, he spoke with his mother for the first time on the phone as a free man.

“I’m out of prison, I’m in a hotel, right, yeah, Ma,” he told her, holding his daughter’s iPhone with three fingers as if he was afraid of the device. “Yeah, it’s awesome. Kristy ran to me, she was crying happy tears, and I was crying happy tears. Kristy bought me a whole mess of clothes and new sneakers—you okay?

“And I look like a teenager even though I don’t look like a teenager. I feel like I got a 50-pound plate,” he said, choking up, “when I seen my daughter Kristy running to dad, and how much she loves her dad, it’s just like the plate came off my chest.”

He also called his ex-wife. Following a dispute she had with her husband a few days prior to Bower’s arrest, she had told her father about the sketch appearing in the local newspaper that resembled her husband. Her tip led to Bower’s ex-father-in-law relaying this information to a member of the Queens Sex Crimes Squad.

Since then she’s filed an affidavit stating her belief in her ex-husband’s innocence and in a show of support attended one of two Sex Offender Registration Act hearings, in Nassau.

Kristy, a former Marine (who told a judge at her father’s Nassau risk-level assessment hearing “once a Marine, always a Marine”), recounted the morning’s events.

“I’ve been thinking about this day since I was a little girl,” she said. “My dad’s always been promising me, every other letter, that one day he’s going to come home, he’s going to make it to graduation, he’s going to be at my wedding, and today, I’m finally taking him home.

“I seen him come right out, and I seen him walking and the other gentleman that escorted him, I just screamed, I’m like,’ That’s my dad! That’s my dad!’” she recalled. “And I jumped out and I ran right to my dad, he dropped his bag and it was an awesome feeling to not have to worry about a C.O. telling you you can’t hug too long, or no kisses on the cheek, or, stop what you’re doing. I always wanted this to happen and today’s the day, so I’m very happy. I’m happy that he’s home.

“And next stop is exoneration,” she continued, nodding her head.

“Yes,” said her father.

“Next step is exoneration,” she repeated. “We’re not going to quit.”

“Not being alone in this hotel room now, I feel like I just hit, I hit the Powerball,” explained Bower. “And, because you don’t need to be rich in the world to be rich, but richness comes from the people who care about you and who are there for you, and love and believe in you.

“And I feel, I feel great,” he continued. “I can’t express the feeling, how I feel. The only one who knows the feeling I got is someone who’s been wrongly convicted, who just got released from prison. And, they know the feeling I’m going through right now. And when you get convicted for crimes you didn’t do, they look at you like you’re a monster and they treat you really bad, and, it’s terrible.

“But, going back to the positive stuff, once I seen my oldest daughter, I said to myself, ‘God, I got the best daughter in the world. I got her right next to me.’ And she’s been there for me 100-percent. And she’s a Marine, she’s a Marine forever, and I love her,” he said, kissing her on the top of her head.

“I love you too, dad,” replied Kristy.

She sat back down on the floor and looked through the stacks of letters and cards she’d sent to her father throughout the decades.

“This one is from Japan,” she said, flipping over a postcard adorned with a photo of Sesoko Bridge—connecting Motobu Peninsula, a part of mainland Okinawa, where she was stationed for part of her military deployment, and the island Sesoko:

Then another—a card with a grey baby cat in a pink dress holding flowers on its front:

“When I got each card I read them over like 50 times,” said a tearful Bower. “Every time I got sad, I picked up one of the cards and I kept reading and reading.

“The cards have so much sentimental value.”

“Hungry Bear”

Looking pale and somewhat paralyzed, Bower sat at a table against the back wall of the log cabin-shaped Hungry Bear Restaurant in Plattsburgh, a few minutes’ drive from the bevvy of restaurants and shops and bars lining Route 3.

For his first official meal besides a hotel bagel with cream cheese, Bower chose the establishment’s signature dish, “The Hungry Bear”: two scrambled eggs with home fries, bacon, sausage, ham, tomato, onion, mushroom, green peppers, cheddar cheese, whole wheat toast, and a side order of onion rings.

“I haven’t had an onion ring in over 25 years,” he whispered, biting into one. “The scrambled eggs they give you in prison aren’t really scrambled eggs; they’re made of powdered eggs.”

He said he’d have to try hard not to say “chow-rec”—prison lingo for cafeteria and the yard—to wait staff before ordering future meals, something that’s instinctual now.

Inhaling his Hungry Bear (which this reporter also enjoyed) in between chomps of onion rings, he offered the last of the latter to his daughter, which she declined, before polishing off his two platters of food.

As we pulled out of the parking lot, he confessed that he had almost lost it in there, that it took all his might not to break down inside the restaurant, convinced that the waitress who took our order somehow knew that he was a convicted sex offender, as if he were wearing a scarlet letter announcing it.

The wind picked up as we headed south and soon the sky opened up with a torrential downpour. The roads were slick and windshield was completely covered with waves of water hurled off speeding tractor trailers. Bower made his daughter buckle up, and he repeatedly locked all the doors within his reach.

“Can I just ask a question?” he said in a soft, shaky voice. “Aren’t you supposed to drive slower when it’s bad out like this?”

This almost childlike wonder and naivety permeated nearly every action and inquiry.

Along the ride, and everywhere we stopped—a gas station, a Dunkin’ Donuts, a rest stop—he remarked on the prices of things he saw compared with what they cost when he’d gone away.

At one rest stop, between the short walk from the car to its entrance he was compelled to ask a woman walking her Chihuahua if he could please pet it. She agreed and he did.

When Bower didn’t return from the men’s room after several minutes, a Press reporter walked inside to find him standing in front of a sink, repeatedly tapping the side of its facet, frantically trying, in vain, to get it to work, since, he remarked, there were no knobs. A sudden unexplained rush of water while he used a motion-sensor urinal was also a cause of near-hysteria.

When the same Press reporter voiced that he’d wished he’d brought his laptop so we could post a story up on the website about the day’s events while sitting down to brainstorm at a road stop Burger King, he implored:

“What’s a laptop?”

Then, a short time later he asked: “Is someone going to come and kick us out of here? Are you sure? Okay.”

Yet while Bower has a lot to learn about the technological advances that have elapsed since his imprisonment, it’s the mandates that will be dictating every moment of his life indefinitely, sans exoneration, that give him the most heartache.

In prison he was able to refuse mandatory sex crimes programs due to his unwavering claims of innocence, which cost substantial points against him during two Sex Offender Registry Act hearings and eventually contributed to two judges branding him his high-risk sexual offender status. But, outside those walls Bower must adhere to a strict set of guidelines and requirements or risk a return to incarceration, something, he says more than once, he simply cannot survive.

First up, his daughter discovered on one of his handouts, was a meeting with his parole officer within 24 hours of his release. Then, with another agency within two business days. Afterwards, once a week for the rest of his life, with a slew of other rules and special conditions.

Neither of them own a vehicle, so Bower will be forced to learn to navigate the city’s bus and subway system, depending on where he’s got to go (despite never using a MetroCard; subway and bus tokens having been discontinued in 2003)—and face countless strangers along the way. It will undoubtedly take some time, and perhaps, anti-anxiety medication and counseling to overcome his fear that everyone knows his standing as a convict, but more troubling is his overwhelming terror that he will be picked up again and “framed” with some additional heinous crime, and thrown back in prison.

On multiple occasions he was beaten within inches of his life while on the inside. Once corrections officers themselves slapped a sign on his cell reading: “RAPIST,” he said. Beneath his relief of being on the outside boils a severe, crippling paranoia that he will once again be “set up.”

Bower is so terrified of this possibility, that he does not want to go anywhere without someone he knows—an impossibility, since his family members must hold down jobs to support themselves, and now, him, since his rap sheet, branding him as a sex offender and his lack of education (Bower doesn’t have a high school diploma) make job prospects bleak, to put it mildly.

Yet one of his “Special Conditions” on his “Certificate of Release,” for example, stipulates: “I will seek, obtain and maintain employment and/or academic/vocational program.”

Bower vows to do whatever he has to in order to comply, fueled by something that has helped keep Kristy and the rest of his family moving forward and kept him alive for the past 23 years: hope.

Hope that the elected officials who hold the keys to his true freedom—District Attorneys Brown and Rice—will put the life of a wrongly accused and convicted man ahead of their political aspirations. Hope that one day the truth will be acknowledged. Hope that an innocent man will one day have his name cleared and the real person responsible for so many heinous crimes will be held accountable.

Hope that after nearly a quarter-century, justice will prevail.

His daughter has been his lifeblood.

“Kristy’s support has been tremendous, because without my oldest daughter’s support, I don’t think that I would have made it,” he said, sitting beside his daughter back in the hotel room in Plattsburgh. “I had thought on many occasions in my cell, when I had got myself extremely depressed, I felt like ending my life. Because, being in prison, for something you didn’t do, especially for something you didn’t do, taken away from your family, thinking that you might spend the rest of your life in prison, it’s been so hard. It’s been so difficult. And I cried almost every day in my cell. I could be having an okay day in prison, I might just get my commissary, and then two hours later I’ll be in my cell crying, missing my family.

“I just want to get my name cleared and I want to be there for my family and I just want to help out as many people as I possibly can and I just want to be there, I want to be the best dad to my children…”

“You are,” she interjected.

“…I want to be the best ex-husband to my wife, I want to be the best son to my mother, I want to be the best brother to my brother, and I want to be the best friend to all my friends.”

“It’s been hard,” said Kristy. “It’s not as hard as him behind a cell, but just being there for my dad, like emotionally and just supporting him in any way I can.

“I always knew that he was innocent,” she continued, her hand on his knee as her dad pats her on the back. “I always knew,” she said, turning to her father. “I always knew you were innocent. And we’d do anything we can to get him out, but it hasn’t been easy. But everything—this is one positive thing, and it’s just going to continue one positive after another, and until, until we have that day in court where…”

“Oh, I can’t wait,” said Bower, shaking his head. “I can’t wait.”

“Exoneration is it.”