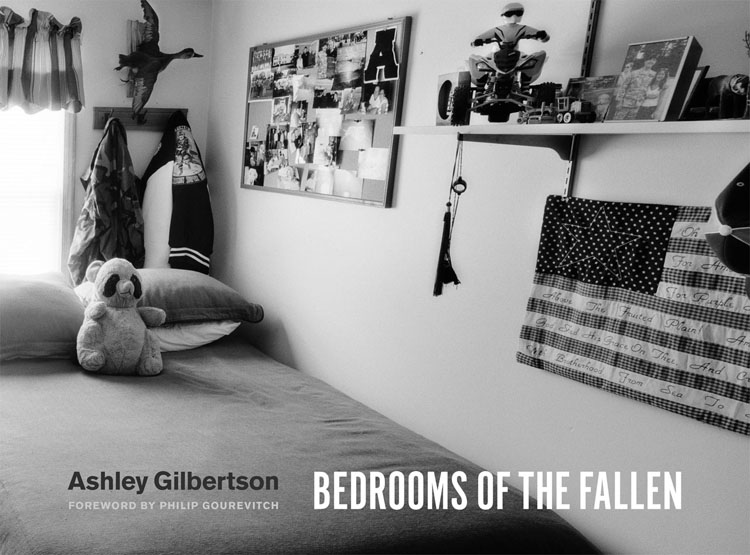

Over Lance Cpl. Jordan Haerter’s bed in his childhood home in Sag Harbor hangs a signed photograph of fellow Marines whom Jordan saved before he was killed in Ramadi, Iraq on April 22, 2008—one month after he was deployed.

Jordan was standing guard at an entry control point at a security station that morning when a truck bomber barreled toward the station. He and fellow Marine Corporal Jonathan T. Yale opened fire until the truck exploded, killing them both. Jordan was 19 years old.

“These guys were not just brave warriors that dressed up in camo,” said his father, Christian Haerter. “They were once children and teenagers who enjoyed the same things.”

Jordan Haerter is one of three fallen U.S. Marines from Long Island whose bedrooms were photographed by New York City-based photographer Ashley Gilbertson for his book, Bedrooms of the Fallen, which was released last month. Since 2007, Gilbertson has taken photographs of the bedrooms of service members from around the world who died in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The bedrooms of 40 men and women—the same number of soldiers in a platoon—between the ages of 18 and 27 are featured in the book. The haunting black-and-white photos of untouched bedrooms provided windows into lives the men and women who called these rooms home.

“I made this book to act as a way of remembering the 40 service members who are included and the thousands of others who aren’t,” Gilbertson said.

Gilbertson started the Bedrooms of the Fallen project after taking photographs in Iraq from 2002 to 2008. His 2007 book, Whiskey Tango Foxtrot, is a collection of photographs from the war in Iraq.

“The longer I worked in Iraq, the more often I would come home thinking that the readers were paying less and less attention,” Gilbertson said. “I started working from home, photographing memorials, Arlington National Cemetery and so on. But I felt those photographs were missing the central idea: absence, the things these soldiers left behind.”

Gilbertson said he got the idea for Bedrooms of the Fallen from his wife, who suggested taking photos of soldiers’ bedrooms after seeing photos of fallen service members in The New York Times.

He found the families of deceased service members through Faces of the Fallen, a database created by The Washington Post of service members who have died in Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom.

SOME GAVE ALL

Jordan’s parents, Christian Haerter and JoAnn Lyles, said that they were a little perturbed when Gilbertson contacted them about the project, but went along with it anyway.

“I thought it was a little strange, but I understood the impetus of whole thing,” Christian said. “It must be a pretty common thing for families to actually leave the bedroom as it is. It took courage to even clean the change he left lying around.”

One of the soldiers who were saved by Jordan was Marine Cpl. Nicholas Xiarhos of Yarmouth Port, Mass. Nicholas’ father came to New York to attend the ceremony in which Jordan was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross in February 2009.

After Nicholas was killed by a bomb in Afghanistan on July 23, 2009, at the age of 21, Lyles attended his funeral in Massachusetts, and Gilbertson photographed Nicholas’ bedroom as well.

The posters on Jordan Haerter’s walls show his passion for flying airplanes. He took flying lessons at East Hampton Airport while attending Pierson High School in Sag Harbor.

After Jordan flew solo for the first time at age 16—before he even got his driver’s license—the back of his shirt was cut out and signed by fellow pilots as part of a tradition. That piece of his shirt, too, hangs on his bedroom wall.

Lyles said although Jordan wanted to join the military, he did not want to be a military pilot.

“He said he wanted to keep flying as a ‘novelty,’” she said. “That was his word for it. A ‘novelty.’”

Jordan was his parents’ only child—a fact that Lyles said allows her to keep his room untouched.

“Anything that makes Jordan name known and remembered beyond me is good for me,” she said. “Everyone needs to realize who we think are heroes were regular people. I don’t think people know that.”

HARD CORPS

Across Long Island, in East Northport, is another fallen soldier’s bedroom that Gilbertson photographed. This bedroom belonged to Marine Cpl. Christopher Scherer, who was killed by a sniper on July 21, 2007, in Karmah, Iraq. He was 21 years old.

The walls of Christopher’s bedroom are still covered in posters and stickers representing local sports teams, especially those of Hofstra University and Northport High School. Christopher’s mother, Janet Scherer, said that in one of the last phone calls she got from her son, he spoke about how much his room meant to him.

“My husband was looking for work down south, so we were thinking of moving, and at the time Chris was deployed,” she recalled. “He said it was lot of hard work to get the room just the way he liked it, so we’d better tear the walls down and take them with us.”

Christopher played varsity lacrosse at Northport High School before graduating in 2004. Only five months later, in November, he officially became a Marine. He was stationed in locations all around the world during his years of service, including Japan, Guam, Singapore, Kuwait, and finally Iraq.

Timothy Scherer, Christopher’s father, recalled an incident in which Christopher’s sisters younger twin sisters, Katie and Meghan, cried over the fact that they would be older than Christopher once they turned 21.

“Something you do as a parent is take care of not only your own grief but also your spouse’s grief and your children’s grief, even on happy occasions like a 21st birthday,” Timothy said. “Even the happy times get taken away.”

Gilbertson’s photographs added a personal aspect to the stories of soldiers who fought overseas, Janet said.

“He really tapped into that emotion,” she said. “That’s my son’s bedroom. That’s who he was. That’s how he grew up.”

PENNIES FROM HEAVEN

The third soldier from LI in Bedrooms of the Fallen was Marine 1st Lt. Ronald Winchester of Rockville Centre, who was killed Sept. 3, 2004 by a roadside bomb that killed three other Marines in Qaim, Iraq. He was 25 years old and had been on his second tour in Iraq.

His mother, Marianna Winchester, recalled that many photographers and reporters came to see Ronald’s bedroom after his death.

“Everything blended together,” she said. “So many photographers were here, and so many newspaper reporters were here. I told them ‘You can use whatever you want because all I have are his memories.’”

Being a Marine ran in the family. Ronald’s maternal grandfather, Dominick Gatta, was a Marine who served in the Pacific in World War II, and his uncle, Rocco Gatta, served in the Corps during the Vietnam War.

“I suppose he wanted to carry on the legacy of what his grandfather had done, or as he said ‘what real Marines were all about,’” Marianna said.

She also said that Ronald insisted on wearing a Marine uniform costume for Halloween when he was only two years old.

“He wore the costume again when he was three and four, and I would just take out the hem,” she said. “Finally it just didn’t fit anymore, and I told him ‘You can’t wear this uniform anymore.’ I wonder if that’s something he kept in the back in his mind.”

Serving in the Corps wasn’t Ronald’s only passion. He played football as an offensive lineman during his years attending Chaminade High School in Mineola and the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md., where he graduated in 2001.

Ronald always used to call tails on each football game’s opening coin toss. Marianna said that, since his death, she finds coins on the ground, always with tails facing up, and that she keeps all the coins she finds in a canister.

I’ll be walking the dog and I’ll say ‘Dear Ronnie, I haven’t heard from you in a while,’ and a few minutes later, I’ll find a nickel or dime or quarter or penny, but never on heads,” she said.

Marianna said that Ronald kept all of his belongings from the Naval Academy and the Marine Corps in his room just the way he liked them.

“I would say to him ‘You know we need to clean up some of this stuff,’” she said. “And he would say ‘Leave it alone. Someday I’m going to get married and I’m going to come back and show my son or daughter so they can see what I was all about.’ He would call it his shrine. He would say ‘Leave my shrine alone because I want them to see me as a hero.’ And he was a hero.”

PICTURES OF HOME

The reaction of soldiers’ families to Gilbertson’s request to photograph their bedrooms is usually positive, the photographer said.

“At first I thought it would be too hard to them,” Gilbertson said. “But over time, I found that these people want to talk about their kids, their lives, their memories. In the end, I’m happy about doing this project if only to have given the families a kind ear. You spend seven years side by side with soldiers in Iraq, but I’ve never felt more like a war photographer than when I’m in these bedrooms.”

Photographs from “Bedrooms of the Fallen” have been featured in the New York Times Magazine and the Nederlands Uitvaart Museum Tot Zover in Amsterdam.

Although Gilbertson said that he has stopped working on Bedrooms of the Fallen for now, he is still continuing another war-related project: photographing the effects of post-traumatic stress disorder and suicide on veterans and their loved ones.

“How disconnected we are with what these people are sacrificing and losing is unfair,” he said. “We have to take time out to remember who these people are and to empathize with their families.”