By Nikki Stern

On Thursday, Sept. 20, 2001, I took Shari with me to Pier 94, the assistance center set up for survivors of the World Trade Center attack. It was Yom Kippur. I was struck by the irony of considering atonement while processing colossal grief.

I was there as a widow and as an observer of history, or so I told myself. I’d already figured out I could maybe cope by acting in part as a detached chronicler of events as they unfolded. Exhausted, drained and isolated in central New Jersey, I hadn’t fully filtered my private loss through the vastness of this public event. Spending 11 hours navigating the bureaucracy of disaster and recovery brought home not only the scale of the devastation but also the mind-boggling support effort underway in New York.

Two hundred lawyers, some barely out of school, were spread across dozens of card tables to help victims’ families file affidavits, a tutorial in the challenges of declaring someone dead whose corpse has not been recovered. My assigned lawyer and I worked with a set of assumptions based on our car found abandoned at the train station, an established routine (he had planned to get to his office around 8:20) and the devastation wrought by a plane flying and exploding at the floor where his office was located). “Presumed Dead” was what we went with.

That brought the ever-present question to the fore: What really had happened? I sought precise information from a Navy pilot, a NYC detective, and an FBI analyst. How much damage can a fully fueled 747 do when it smashes, nose first, into the side of a glass building? How quickly? What variables might affect the outcome? No, I don’t know where he was sitting or whether he was sitting or whether he was at his desk or in the men’s room. No, we didn’t talk that morning.

My “investigation” gave me something to do. I was establishing the facts of Jim’s death. I decided it must have happened nearly instantly. I just couldn’t decide whether getting a call from him one more time made me lucky or unlucky. Didn’t really matter.

We signed up for an excursion to the site. Looking back, I wonder that family members had insisted on visiting the devastated and potentially dangerous site and officials had agreed to arrange those visits. We were all trying to make sense of something that made no sense. And no one was saying no to the grieving survivors.

Logistics were still in flux and the boats were delayed. As the minutes passed, my already short fuse ran out. I kicked a folding chair across the room, which skittered and collapsed with a bam! Heads swiveled. People actually gasped. I was rushed by aid workers speaking English and Spanish (“Cálmese,” or cool down, they said), but Shari—a friend and coworker—got to me first.

“Grief is for here, anger is for home,” she whispered.

At last we were led through a double line of soldiers in front of boxes that might have contained computers—or guns. Once aboard, police chaplains, counselors and grief dogs surrounded us. Steely-eyed men dressed in black and carrying fearsome-looking firearms faced out over the Hudson. The boat passed the quintessentially New York bluffs that make the Hudson River landscape so unique. If I squinted, I could just make out machine guns perched at the summit. Helicopters hovered protectively overhead. Motorboats circled our ferry, each containing grim-looking armed soldiers. A lovely day for a weapons-heavy water processional.

We rounded the tip of the island of Manhattan and came upon a sight both alien and awful. Sunlight glinted off the smoldering ruins of what had been the World Trade Center. Smoke and ash and God knows what else colored the sky a sickly yellow.

Welcome to Hell.

Off the boat and onto a specially built platform, I expected to fall weeping to the ground, but detached and observant me was in charge. While family members wept softly behind me, clutching flowers and teddy bears, I spoke conversationally with the cleanup crews, asking smart questions about schedules and workloads, and machinery and debris. No one mentioned what that debris might have included.

I gave myself time to look around. The terrible beauty of the site appeared as some terrifying piece of public art. I turned in a circle, trying to superimpose the before onto this ungodly after. Was this where I’d get off the subway to meet Jim? Was that where he worked? I knew he had been here, just as I knew he wasn’t here now. But where was he?

In the charred park behind what had been the World Financial Center, family members laid down their wreaths and stuffed animals. I separated from the group, walked up the few steps that remained, and whispered, “You’re not here” and kicked at the stone. I repeated, sotto voce “You’re not here!” and kicked at the stone steps until I tore my shoe.

A gentle hand restrained me. A kind and worried face appeared. Would I like to get back on the boat now? Turning around, I saw the other passengers already lined up to board, staring at me with a mix of pity and fear. The clinical me had failed to remember: Grief is for here; anger is for home.

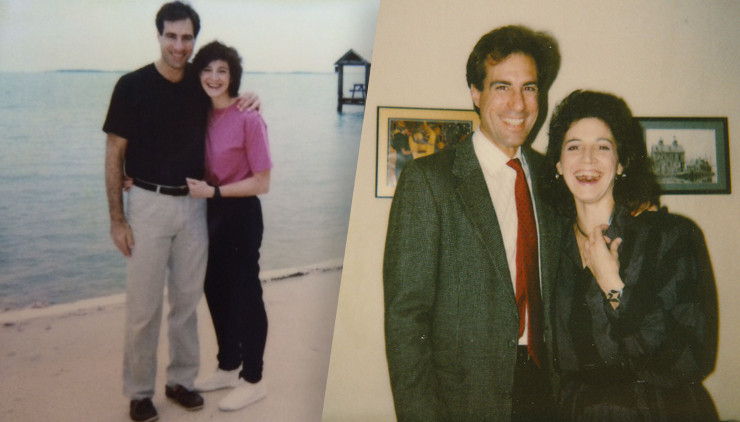

Nikki Stern is an author whose latest book is Hope in Small Doses. She is the former executive director of nonprofit Families of September 11. Her husband James Potorti was killed at the World Trade Center on 9/11/01. The couple lived on Long Island in the early ’90s; James “adored” Long Island, says Stern.