Beginning in 2010 a nonprofit group called Seeing for Ourselves trained over 200 residents living in New York City’s housing projects in photography, gave them Kodak disposable cameras, and sent them out to document their day-to-day lives in what amounted to the largest program in participatory photography ever undertaken.

The result is remarkable. Project Lives: New York City Public Housing Residents Photograph Their World is a small book that, in words and pictures, delivers a very big punch. Each turn of the page is a visit into the homes and lives of people most of us rarely see and would not recognize on the street yet their presence is vital to the city and its economy.

Since its April 2015 launch and accompanying photography exhibition in DUMBO, the fashionable upscale Brooklyn art center, the exhibit has traveled to Patchogue Artspace, an innovative affordable-housing center for Long Island artists. While there are many Artspace affordable-housing projects for artists across America, this is the first one on Long Island. Although that show has closed, Long Islanders will get their next chance to see this remarkable exhibit later this month at fotofoto gallery in Huntington.

New York City is where affordable public housing began in the 1930’s and where its survival is at stake under the unrelenting pressure of cutbacks in government funding on the federal, state and city levels. An estimated 400,000 low-to-moderate income residents live in the 2,563 buildings that comprise the 334 public housing projects. But most of us never know anything about them until something horrible occurs that commands the front pages of the city tabloids and dominates the evening news.

We live in an age where amped-up violence is rampant, accentuated and marketed. Project Lives is the complete antithesis. What is extraordinary about this book is that it is so normal, real and readable—and some of the photographs are absolutely brilliant.

The soulful expression, for instance, captured by Margaret Wells of the elderly man standing in the kitchen and dressed for church is so poignant and genuine. His resignation to attend the weekly ritual is a visual contradiction to the halo-like light fixture above his head. In all likelihood it was not intentional, but it was captured.

The snowflakes on the window of her apartment intrigued Helen Marshall. This dark photograph is filled with the light of her creative mind and stands apart from all the other photos as this one gravitates to the abstract. The famed photographer Dorothea Lang once remarked that “the camera is a tool that helps us see,” and Marshall has allowed us to see beyond the obvious.

The photograph of the chalk drawings on the red playground by Sheik Bacchus makes me think of Miro’s constellation paintings where he symbolically connected the celestial to the terrestrial. This child’s creative sprawl dwarfs the green box of chalk, and all that we see of the maker is her lower torso with pink painted nails. The mystery is pink-alicious.

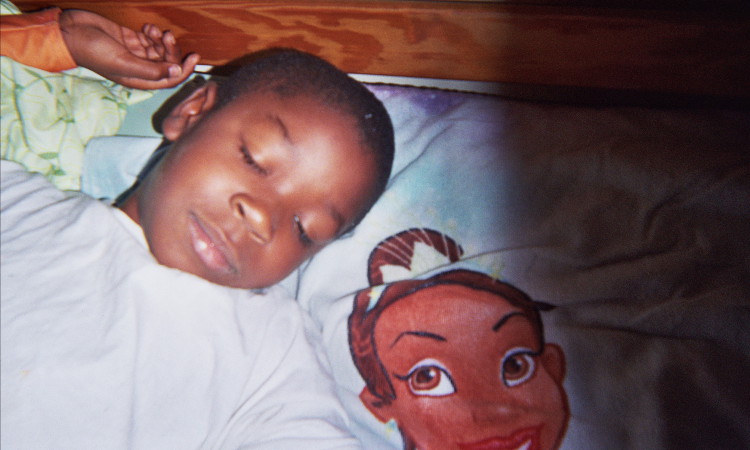

Aaliyah Colon photographed the face of her sleeping brother tenderly juxtaposed with the wide-awake face printed on the pillowcase. How simple and pure…what dreams and thoughts are drifting within the tranquil innocence of that sleeping child. And I wonder what his day will be like when he awakens.

The mystery and melancholy of the shadows on the sidewalk in the photograph by Jared Wellington immediately brings to mind the foreboding in the paintings of Giorgio de Chirico, the Italian artist whose work influenced the Surrealists. I am almost certain Wellington knows nothing of de Chirico yet…but he may in the future.

Wellington’s evening photo of his cousin roaming around the neighborhood is mighty potent. The glow of the night-lights complements the child’s expression perfectly. What ideas churn behind those wide-open eyes…and those eyes continue to follow me even when I am not looking at him.

These are but a few of the 80 photos in this book, and I can go on and on discussing them. Yes, they were taken in the housing projects but they are universal icons of daily life in America in our time. Their unpretentious truth has the power to change how we see life in the projects. Perhaps, we may even become more sensitive to our own daily lives as well as to each other wherever we live.

These pictures might have been plucked from any of our smart phone or family albums. But it was New York City housing project residents from children to seniors, with no previous photographic skills, who documented their lives. Their photos and words are filled with hope and love and family and life, even though they live in an environment where the deck certainly seems to be stacked against them.

The three editors of Project Lives, George Carrano, Chelsea Davis and Jonathan Fisher, prompted by their lifelong relationship with NYC, envisioned this participatory photography project and with singular determination brought the idea to actuality. For the first time, nearly half a million residents of the New York City housing projects have been presented with the opportunity to tell their own story and not have it told for them.

This book brilliantly and succinctly weaves background information into the photos to complete the whole picture of life in the projects. Exuding sensitivity, humanity and love for the city and its people, it has the power to be a mind-changer, forcing us to shed the stereotypes that have filled our thoughts with negativity, violence and waste for far too long.

In conjunction with the upcoming exhibit at fotofoto gallery in Huntington, we spoke with one of the key forces behind the lens on “Project Lives,” George Carrano, who brought the Developing Lives photography program to the New York City Housing Authority in 2010 and helped oversee the publication of the book and the creation of the show.

Long Island Press: So what led you to “Project Lives”?

George Carrano: “I started working for the New York City Transit Authority back in the ‘70s and the garage where I was working in is directly across from the street from the Manhattanville Houses, which is a very large housing project in Harlem built in the late ‘60s. So I used to walk through there on the way to work and I never felt threatened, never felt uncomfortable. It was just another New York community. The 1970s’ “Cooley High” was the last Hollywood film where the housing projects were shown in a favorable light. Since then, I started seeing this contrast between the reality that I experienced and the way residents in housing projects were being portrayed in films like “American Gangster,” with Denzel Washington and “Brooklyn’s Finest” with Richard Gere, where the projects were described as “Bagdad on a bad day.”

How did you come to team up with Chelsea Davis and Jonathan Fisher on this project?

Carrano: Jonathan Fisher also worked at the Transit Authority and we became life-long friends. When we decided to do this project in 2010, we came upon Chelsea Davis, who was doing this kind of photography project in a children’s hospital in St. Louis, where she worked with children with cancer and used photography to deal with the tragedy of living with cancer.

What inspired you to see this through?

Carrano: I think it was the unfairness of seeing the way hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers were being portrayed and feeling that something should be done about it. The tabloids and the Hollywood films had deprived housing residents of their public voice by portraying them all as violent offenders. And we felt that the most authentic way to push back would be to have the residents themselves tell their own stories and talk about their own lives. So this participatory photography concept became a vehicle for story-telling. It allowed those whose public image had been defined by others to take control of their own narrative. That’s what was driving this project from the beginning.

Did you envision a book from the beginning?

Carrano: The first instance was to have an exhibit of their photographs, but then we thought of a book because affordable housing is really a national issue. And New York is where public housing all began back in the ‘30s. It’s the last stronghold for public housing and we felt there would be national interest. What made public housing successful in New York was the triple subsidy: the city, the state and the federal government came together with Franklin Roosevelt in the White House and Herbert Lehman in the state house and Fiorello LaGuardia in Gracie Mansion, and that allowed public housing to begin. Since then, federal cuts to public housing have been steadily declining and the deficits are now huge. Major rehabilitation of the housing stock is needed. And we hoped that the book would spark a national discussion about federal funding to public housing.

How did you make your final selection?

Carrano: We probably could have done a much bigger book but for this project we chose to use Kodak disposable cameras, which offer 27 shots per camera and they’re on film. The cameras cost under five dollars each, whereas a digital would be a couple of hundred dollars. And you have a film negative that you can blow up to a huge size, and to get a digital equivalent of that would require a fairly expensive camera. We didn’t have the funding for that. And, at the same time, 27 shots taught a certain economy of selecting and composing consciously, knowing that you had a limited number of frames to play with. Sometimes with digital photography, you can shoot off a hundred pictures in a matter of seconds. This really forces you to think about composition and know that every single shot had to count.

How did you get these people from the projects involved?

Carrano: People were eager to participate. We ran the project in 15 different housing projects across the city from the Bronx to Brooklyn. Kids and seniors just gravitated to the program. There was a lot of excitement about it. Kodak donated hundreds and hundreds of the single-use cameras, which helped reduce costs. The three of us spent a lot of time going through the pictures and through the bios of the photographers. It was a long, hard process to come up with the photographs that are actually in the book. Even with the limitations that we had imposed on ourselves of only 27 shots per camera we still had enough photographs for a couple of books. So it required a lot of discriminating selection by age, by location, by issues. It was our job as editors to come up with a coherent book.

Did the participatory process pose any problems?

Carrano: People today are far more protective than in the period of Henri Cartier-Bresson and street photographers of his era. People didn’t have the same sense of themselves being photographed. Today people have to feel very comfortable around who’s taking pictures. These [issues] were all part of the workshops that we ran. We went to the masters; we showed examples of great photographs. We talked about composition, about lighting. We gave a 10-week program that was a serious photography program for all the participants.

How much aesthetic judgment went into the final selection of these images compared to the political importance of showing these lives that have been stereotyped in the media?

Carrano: What surprised me most about the project is that we didn’t get a lot of pictures of disrepair, of broken elevators and broken windows. The photographs actually portray a kind of benign banality of daily life. A kid walking in the park, someone sitting in their kitchen.

Does that normalcy undercut the significance of these photos? There’s no buzz: no murder victim on the sidewalk?

Carrano: I think the spark comes from the fact that it’s not what people expect to see. They’re going to be surprised and wonder about these pictures. If you just read the tabloids and see the movies, you’d expect to see kids collecting shell casings on a Saturday morning, not kids playing basketball in the park. These pictures are the reality.

Did all three of you editors have to agree on whether a particular image made the final cut?

Carrano: The three of us are all consensus builders! We all shared many favorites. The one I liked the best is from the Bronx of two women, one looking out her window and the other standing on the sidewalk because it just conveyed to me a sense of community. I grew up in the Bronx and it just took me back to that sense of neighborhood and people watching out for each other. [Editor’s note: The caption of Jane Mary Saiter’s photo says simply: “My neighbors.”

Can a typical suburbanite view these photos without bias?

Carrano: Everyone brings some bias to looking at anything. There are those suburbanites who were part of the urban flight from the city at one point in time, although there’s also been a counter stream of people going back into the city and rejuvenating neighborhoods that were once abandoned. I think the connection is really about American lives. Even if their circumstances aren’t the same, the same joys, hopes and concerns go across both groups.

Did you get photos of crime scenes and other disturbing subjects?

Carrano: No, we left that to the tabloids. We didn’t get pictures of crime scenes and disrepair. People were told to go out and document what’s important to them. We were taken aback that we didn’t see these pictures of disrepair. It took us time to understand that this was really a vehicle for people to tell their own stories and what’s important to them. And the story they wanted to tell was not one of disrepair, but of the day-to-day joys of living.

What more do you have in mind for ‘Project Lives’?

Carrano: I would like to see the resident photographers who participated in this book have an opportunity to testify in Congress on hearings that focus on affordable housing. Sympathetic Congressman could hold ad hoc hearings in the Rayburn building and bring together like-minded Congress-people to hear testimony of people living in public housing. That would be a valuable way to shine light on this issue.

It’s interesting that the banality in itself is political in the context of the debate over public housing.

Carrano: What comes to mind when you hear the words ‘housing projects’? Nothing good comes to mind because everything the public has been bombarded with has been negative. I think of a Congressman from Idaho going to the movies on a Saturday night and seeing the movie, ‘American Gangster,’ and then going into the halls of Congress and voting on an appropriations bill for public housing. How’s he going to vote? This is pushing back!

Do you think we’ve seen the end of public housing projects like this?

Carrano: I hope not! I think it’s needed. For a studio apartment in Manhattan the average going rate is $2,350 a month. Getting a one bedroom or two-bedroom apartment in the city, where would these people go if you lost public housing? Where would low-income people go? The people working in fast food and the hospitals—people whose jobs pay the minimum wage—where could they possibly go? It’s necessary. It’s one of the four freedoms that Roosevelt talked about.

Is “Project Lives” more a political book or an art book?

Carrano: Art is political. I don’t want to use ‘political’ as a pejorative word. The book tells a story; that’s what this book does, and it can have political implications. But it’s basically using photography to tell a story about the lives of those living in public housing whose voices haven’t been heard.

How should viewers approach your photos? Should they say, ‘Oh, that’s what a project looks like inside!’ Or should they marvel at the light and the composition, for example?

Carrano: I would want them to look at it and say, ‘These are people just like me! Their lives are very similar to my life.’

And that should be a revelatory experience in itself?

Carrano: Yeah, that’s it exactly.

Exhibit runs from July 31-August 29 at fotofoto gallery, 14 West Carver St., Huntington. Gallery is closed Mondays and Tuesdays; check for hours.

Holly Gordon is a working fine art photographer whose work has appeared in published form and in museums and galleries. George Carrano, Chelsea Davis and Jonathan Fisher (eds): Project Lives: New York Public Housing Residents Photograph Their World. Brooklyn: powerHouse Books 2015.