It’s been more than four decades since I graduated from the bankrupt New York Military Academy, which was just sold after a bidding war to a China-based investor on Wednesday. For six years I’d attended this private boarding school in Cornwall-on-Hudson, some 60 miles north of New York City. I’d been exiled up there by my father, a lawyer and institutional fundraiser, who had abandoned his enthusiasm for Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophy, an educational scheme directed by spirit voices, and had become convinced by Fred Trump, his business acquaintance, that a military immersion was just what I needed to flush all that spiritual nonsense out of my system.

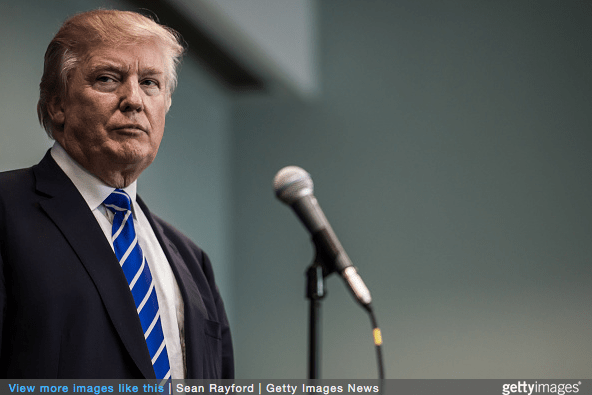

Before I entered military school I spent the summer at the Atlantic Beach Club on Long Island, where the Trumps were also members. Donald, taking the part of an older brother, taught me daily to play Canasta and other card games. But once the school year began, Donald was already in the upper school, while I was in the junior building. We did pass each other occasionally and would talk between roll calls. Throughout my acquaintance with him, he was always kind, though he never laughed at my jokes.

In practice, hazing at the military school was conducted by both adolescent cadets and our adult supervisors. In their first year, cadets were subjected to ritual “New Guy” rules, which included recitations on demand of silly rhyming formulas for telling time or listing the supposed functions of a cow, throwing oneself against the wall to make room for an Old Guy to pass, or even belching on command.

In the students’ later years, it included more serious ritual hazing applied as punishment for disciplinary infractions or poor grades. One of the most feared tasks required those about to be hazed to appear in the basement shower room, where the 10 or 15 shower heads would be blasting hot water, which created a steamy fog that burned the throat. The unfortunate cadets would have to appear in their heavy-padded winter dress uniforms. They would stand at rigid attention with their arms raised parallel before them, balancing their eight-and-one-half pound M1 rifles across their arms. After 10 minutes, the M1 seemed to weigh 50 pounds. Anyone dropping his rifle was taken into the next room to be physically reprimanded.

Hazing at NYMA reached its climax in my time on the 75th anniversary of the school’s founding in 1889, with a reporter from The New York Times attending. On the eve of that celebration, the cadet captain of the feared “E” Battery proceeded to punish one of his charges by flogging him repeatedly with a heavy metal chain. In the middle of the night, the cadet who had received the beating went AWOL. He escaped the school grounds and found his way to a hospital, which treated him and called his parents, who called the State Police. As a result, the adult staff, including the Commandant, the Dean and even the Superintendent, were forced to resign, effective immediately.

My friends at home on Long Island wondered why I didn’t quit the place. I’m not sure why I stayed; it was a kind of grudge match I was playing, daring myself to hang on and graduate. Meanwhile, Donald Trump, I couldn’t help but notice, was swanning his way through the years, becoming captain of both the football and the baseball teams, and in his last year, attaining the highest cadet rank, First Captain. At the same time he maintained the hazing tradition of those beneath him, while seeming untouched by it from above. I see a continuity between the old school ways and his present political activities, in which he encourages his Republican adversaries to haze one another while he remains elusive, barely touchable. Though mostly concerned about my own mucky survival, I watched Donald maneuver the adults, getting them to do things his way—a manipulation I would have had no idea how to perform. The furthest I got was to be labeled a suck-up when I imitated Donald’s methods.

Eventually, not through military merit, but through whining and complaining, I rose to a rank in my senior year that allowed me to live somewhat independently outside the hazing culture. Perhaps I owe this to Donald.

In any case, I swore I would never donate a cent to the military school. And I suspect that it was this attitude shared by other graduates that doomed the place. I remember a letter to the alumni scolding us for failing to donate, as grateful alumni of other boarding schools always did. And now I can say that one of my wishes has been granted: I have survived the existence of NYMA, which filed for bankruptcy in March. At the announcement of its closing there was news that an Upstate Chasidic community might take it over. Now, Chinese investors have staked their claim. One way or the other, it makes me neither happy nor sad. There is a rule in the buying and selling of all kinds of property, that once the deal is done you never turn back to look at it. There are no second thoughts. I once again reflect on Donald Trump, who, when asked to donate 7 million dollars to keep his Alma Mater afloat, refused unemotionally, considering it to be merely a bad investment.

===

Sandy McIntosh has published 11 volumes of nonfiction prose and poetry. He has been Creative Writing professor at Hofstra University and published in The New York Times, Newsday, The Nation, the Wall Street Journal, American Book Review, and elsewhere. He has been managing editor of Long Island University’s Confrontation magazine, Marsh Hawk Press will publish his memoir, “A Hole In the Ocean: A Hamptons’ Apprenticeship” in early 2016.