When the Cubs made the final out last week in Chicago, long-suffering Mets fans back home were ecstatic. The line for Modell’s Sporting Goods in Plainview stretched across the shopping center parking lot as people waited after midnight for the chance to commemorate the newly won National League pennant by buying an official baseball hat for $35 or a jersey for $110—a World Series patch raised the retail price an additional $15.

Sports always have an interesting effect on people’s judgment. All one has to do is look at Mineola’s efforts to convince themselves that the New York Islanders will come back. Whether it’s a local government financing a $900 million stadium or fans buying hundreds of dollars of souvenir memorabilia, professional athletics have a funny way of convincing people to spend their money when they know they’re getting hosed.

The Mets, for this season at least, are New York’s team. So goes the fortunes of ball clubs: when you’re on top, you’re the king. When you lose, fans want to throw the bums out and bring in new blood. Somewhere, Yankees fans are counting their 27 championship rings while they wait for next season.

This passion for the home team runs deep – local sports franchises know it, as do the municipal governments that house these teams. The logic is that voters love their teams – and any politician who loses a franchise will rue the day the club packs their bags and leaves town. It is with this knowledge that sports organizations negotiate for new stadiums, arenas and ball parks.

Trying to cater to professional teams isn’t exclusive to Mineola, for even relatively level-headed policymakers succumb to sports madness. Before leaving office in 2002, Mayor Rudy Giuliani doggedly tried to push through a flawed $1.6 billion plan for two new stadiums in New York City. The New York Times editorial board said the mayor’s emotional attachment to baseball had “warped his judgment.” The proposal was axed by Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who eventually floated his own eventually successful proposals to replace both aging venues.

Locations for a new Yankee Stadium were debated, but the site selection for Shea’s replacement was easy for the Mets. They could build their new monument to America’s pastime in as much of a convenient spot as you can get: the parking lot next to their existing stadium.

Both New York complexes have transit and highway options, which helps determine the geographic concentration of fandom. The better the access, the more fans see baseball—an asset for any team to get people to the game, and revenue into their coffers.

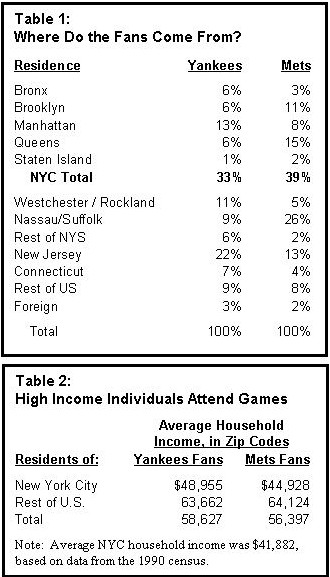

The access theory holds, because the New York demographics of New York fandom tell who, exactly, these stadiums cater to. In a 1998 report by the city’s Independent Budget Office, the authors “attended games at each stadium and asked about 1,000 attendees at each game for their zip codes.” The breakdown is a bit enlightening:

Not surprisingly, Long Island was the principal home of Mets fans for those particular games, while the Yankees can thank New Jersey and Manhattan for the fannies filling their stands, thus lending merit to the argument that easier access can drive fandom.

The geographic trends found in IBO’s 1998 report were further supported from more recent (and comprehensive) data released by Facebook in 2014, which measured MLB fandom by the number of people’s LIKES on each team’s page. While the Mets are the talk of the town these days, the disparity between Facebook users who showed a preference for the Yankees outnumbered those who liked the Mets almost 3 to 1.

As the Times wrote in their data analysis: “The Yankees are the preferred team everywhere in New York City, and nearly everywhere in the U.S. over the Mets (in more than 98 percent of ZIP codes nationwide).”

What all this data means is that stadium policy doesn’t necessarily cater to the residents that city officials and sports teams always assume it does, nor do the suggested economics bring in the out-of-region revenue assumed. Sports franchises always state that these stadiums will benefit their particular city itself, when in reality, wealthier suburbanites reap the benefits of the increased transit availability and associated stadium amenities.

While detailed analysis has been conducted by IBO concerning both the economics of Citi Field and the new Yankee Stadium, the findings are almost the same: “…findings from econometric studies across the nation consistently agree: taken together, baseball teams and stadiums do not spur economic growth in a metropolitan area.”

While IBO found that stadiums aren’t the economic powerhouses they are touted to be, the group did mention that integrating restaurants and retail into stadium neighborhoods would have a positive fiscal impact. Only a comprehensive approach to development would extract the maximum economic potential of a newly constructed stadium. Smart development in these areas would not only keep visitors in the area longer on game day, but during the offseason as well.

If executed correctly, these areas could help bolster the ball parks in order to bring newfound economic prosperity. But it’s an uphill battle, whose odds of successful implementation hinge on the strength of the regional economy. The problem, of course, is one of coordination. How would a development at Willets Point interact with one of the many projects being built in Nassau or Suffolk County?

As Long Islanders and Queens residents pour into Citi Field to watch the Mets take on the Royals, city officials should understand that the economics of sports isn’t always a home run. After the city invests hundreds of millions of dollars into the Bronx and Queens for improved transit access, demolition of both old stadiums, the foundations of the new ball parks, and in the case of Yankee Stadium, relocation of displaced parkland, is it worth it for the typical New York City resident?

To the thousands of suburbanites who fill the stands, and afterwards leave the area by car or train, it doesn’t matter, for they reaped the benefits of that sizeable public investment…all while wearing a $35 hat.

Rich Murdocco writes about Long Island’s land use and real estate development issues. He received his Master’s in Public Policy at Stony Brook University, where he studied regional planning under Dr. Lee Koppelman, Long Island’s veteran master planner. Murdocco is a regular contributor to the Long Island Press. More of his views can be found on www.TheFoggiestIdea.org or follow him on Twitter @TheFoggiestIdea.