By Sandy McIntosh

At the Los Angeles Convention Center this March, 12,000 to 15,000 writers, members of the nation’s graduate creative writing programs, will meet in workshops and networking parties at the annual Association of Writers and Writing Programs gathering. They’ll be representing thousands of fellow writing students, many of whom will shortly graduate as fully qualified poets.

That’s a lot of fully qualified poets!

Given the lack of openings for poets in the job market, one question they must ask themselves is: “What will happen to me outside the walls of academia? Has there ever been a real, vital life out there for the serious writer?”

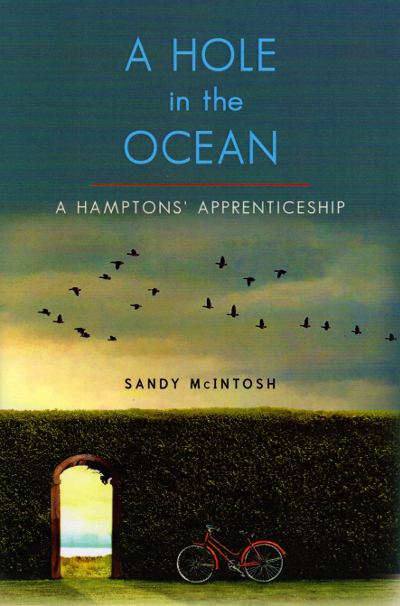

My new memoir, A Hole In the Ocean, a Hamptons’ Apprenticeship, offers an answer.

Back in 1970, when the East End of Long Island was a quiet, difficult-to-access refuge for painters and writers who’d washed up on its shores from cities and towns around the world, I enrolled as an English major at Southampton College. The college, now Stony Brook/ Southampton, was then the furthest outpost of Long Island University. It had been founded to teach the children of the year-round residents, the workers living in the towns along the East End shore.

What I found were teachers unlike any I’d met. Not merely scholars, these professors were the real thing: writers and artists of national, even international repute, quietly spending their winters in a warm and collegial place.

These were artists such as Willem de Kooning, Ilya Bolotowsky and Ibram Lassau, and award-winning writers such as H. R. Hays, David Ignatow and Charles Matz.

Why had these accomplished artists gathered at a small, rural college? De Kooning once explained it to me: “We’re here in the wintertime. We work in our studios all day and some of us want to get together at night, usually at some bar. Then people get drunk and into fights and the police come. But now we can meet at the college and talk, and we don’t get into too much trouble.”

A Hole In the Ocean is my recollections of these unique artists I got to know on campus and off. Instead of classroom instruction, these craftsmen offered me their criticism, as well as their friendship, for many years to come. In return I played unofficial chauffeur, therapist, straight-man and witness to their successes and foibles.

And I learned that it was possible to live as a writer and as a member of a supportive—if incessantly quirky—artists’ community.

One summer evening in 1970, after my shift pumping gas, I was driving home along Springs Fireplace Road in East Hampton when I had to brake suddenly to avoid hitting a tall, thin man on a bicycle. He had swerved out of a side road, and crossed in front of me without looking. I pulled over to catch my breath. As I drew closer, I recognized Willem de Kooning, whom I had met at Southampton College during my first year. I watched as he rode along, pedaling uncertainly, his bike weaving figure eights from right to left. At one point he seemed to lose interest in pedaling. The bike came to a stop, stayed motionless for a moment, then pitched over to the right, its rider falling gently into the thick, uncut brush and rolling two or three times until coming to rest under some trees. I shut off my car and ran over to him. He didn’t seem hurt; in fact, he was smiling pleasantly, his eyes closed as if dreaming. I touched his arm and he looked up. He was okay, he told me, but could I give him a ride home? It was getting dark and he had no light on his bike.

I helped him into my car and loaded his bicycle into the back seat. He told me to continue east, then take the right fork before Barnes’ grocery store. He was living in a farmhouse opposite the Green River cemetery, he said, but this was only temporary, until they finished building his new studio. “I don’t want them to finish the damn thing,” he said with some bitterness. I asked why not? “Because when it’s finished, I think I will be finished, too.”

We drove on for a few minutes until he told me to stop. “I live right here,” he said. He looked in the direction of the cemetery and pointed: “All my friends are buried over there.”

I was curious. I helped him out of the car and to his front door, and when he was safely inside, I crossed the road to the cemetery.

It seemed a conventional graveyard with moldering tombstones. But then I caught sight of a grave marker that was odd. It was an obsidian monolith standing about four feet high. Engraved on its face was a man’s signature: the painter Stuart Davis. Looking around in that section of the cemetery, I found other oddly shaped stones, each with the name of an artist or a writer I had heard of. In front of Stuart Davis’ grave was a white marble square that marked the grave of Ad Reinhardt. I discovered the flat slate grave maker of Frank O’Hara, the New York School poet who had been run over by the only vehicle on Fire Island. Inscribed on it was his quotation: “Grace to be born and live / as variously as possible.” Just north of O’Hara’s grave was that of the writer A. J. Liebling, the war correspondent, boxing expert, world-class eater, and, for many years at The New Yorker, a critic of the press. Finally, at the end of the cemetery, almost in the woods, a great boulder with a bronze plaque marked Jackson Pollock’s grave. I continued on, following the horseshoe road until I came to a fence. On the other side were objects—gravestones, I thought—that were extremely weird, even grotesque, resembling Native totem poles. I wondered about that section of the cemetery for a long time. (In fact, I learned eventually, the odd objects were not grave markers but rough carvings in the side yard of the sculptor Albert Price’s house.) Later I described the little graveyard to my friends as a place “with dead people on one side and artists on the other.” I visited the place often, even picnicking and napping on an artist’s plot that was behind some trees, out of public view.

The cemetery was a quiet place in all seasons, and from Labor Day to Memorial Day around 1970 the noisy Hamptons’ main streets were quiet, too. The only businesses open after 8:00 p.m. were the bars and cafes, each town supplied with one or two of each. Standing on Main Street you could actually hear the crashing of ocean waves a half-mile away, a sound reverberating against the empty sidewalks and closed summer stores, surprisingly primitive and frightening.

——

Green River Cemetery has been expanded by at least an acre or two behind Pollock’s boulder. Artists and writers continue to be buried there, and who they were and what they are famous for reflects something of the upscale attraction of the modern Hamptons. Filmmakers such as Stan Vanderbeek and producer Alan Pakula are buried there, as is the celebrated French chef, Pierre Franey, to name three. The cost of graves, I understand, is prohibitively expensive, except for the very wealthy—as is everything else thereabouts. Even so, the cemetery was silent at my last visit as all of the Springs had once been, even at the height of summer. I reflected on my encounter with de Kooning long before, and had the sobering thought that in subsequent summers a tipsy artist wobbling on his bicycle in a Hampton’s road would have little chance of surviving the tourist traffic, which is grim, relentless and unforgiving. In fact, I realized, the easy access I had in my time to the wonderful artists and writers living there may no longer be possible. These days they all seem to remain cloistered in their compounds, their public appearances protected by bodyguards.

At Canio’s bookstore in Sag Harbor some years ago, Harvey Shapiro read a poem called “For Armand and David” that touched on feelings shared by those of us who have considered the Hamptons a refuge for our poetic selves.

“When we were young,” Shapiro’s poem begins:

And our children were young—

the water was such a mystery,

the sky so blue. Everything

breathed promise. The language

would blaze forth,

did blaze forth…

To the rich vacationers

our lives meant nothing.

We kept investing them with meaning

until the enterprise broke us.

…

I see these same sights,

bleared now. Words

broken into stony syllables,

blackened in remembrance.

At the end of 1970—and as we did each year back then—Armand Schwerner, David Ignatow, Harvey Shapiro, Hoffman Hays, Allen Planz, Sy Perchick and others of us gathered during November or December to celebrate some last event before winter. A few times I remember Armand grunting a kind of benediction to end the season.

“And now,” he’d pronounced in his ominous tones, “for four months of shit.”

We’d look up into the grey sky, and that would be it till we’d meet again in spring.

Sandy McIntosh is the author of eleven volumes of poetry, as well as books on business, cooking, and a best-selling computer software program, Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing! He taught creative writing at Hofstra University and Long Island University. He was managing editor of LIU’s Confrontation magazine. He is publisher of Marsh Hawk Press.

(Featured photo illustration: Ken Robbins)