Real estate executives were celebrating successfully bankrolling their Republican allies’ campaign to recapture the New York State Senate majority five years ago when one question turned the mood from upbeat to tense.

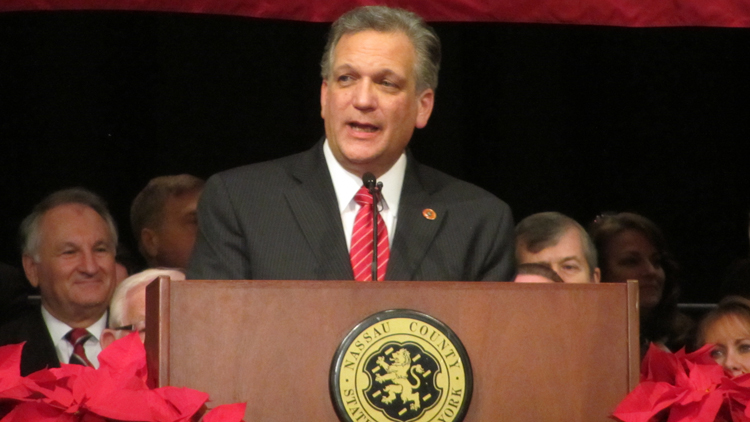

With their help, then-New York State Sen. Dean Skelos (R-Rockville Centre), 67, was about to become the senate majority leader. But then he asked billionaire Leonard Litwin, owner of New Hyde Park-based developer Glenwood Management Corp.—the state’s biggest political campaign donor, which lobbied Skelos on key real estate legislation during the celebratory meeting—if the company could direct title insurance work to the senator’s 33-year-old son, Adam, a witness later recalled.

“I felt it was peculiar because I thought the senator was there to thank Mr. Litwin, not ask a favor,” the witness, Charles Dorego, told a jury when he testified during the senator and son’s corruption trial at Manhattan federal court.

“We had major legislation in front of the state Senate,” said Dorego, who had grown up on the East End of Long Island to become general counsel and vice president at Glenwood. “I was being asked directly by the head of the Senate to do these things, and I felt that there was a connection between the two that could be adverse to our business.”

Dorego said he and Litwin looked at each other “in recognition of the statement,” which came as others in attendance were leaving the Dec. 20, 2010 meeting at Glenwood’s headquarters on Union Turnpike. After Skelos left, Litwin, now 101, told Dorego: “Let’s not do anything,” Dorego, 61, testified.

The scene marked the first of dozens of requests the senator and his son made to Dorego and others, ultimately extorting three companies out of about $300,000. Prosecutors presented evidence of those requests detailed in hundreds of emails, dozens of wiretapped phone calls and a hidden audio recorder worn by one of the 20 witnesses that testified in the month-long trial that ended with Adam and Dean being convicted of corruption charges Dec. 11. Although many details have been widely reported, context was often lost between the pace of news coverage and the court testimony jumping from one date to another, blurring significant moments in the timeline of the conspiracy. Seen chronologically in full, it offers a revealing look at the raw power that money has in The Empire State’s politics, and the abuse of this state’s most trusted offices to capitalize on that power toward a lawmaker’s personal objectives.

To review, the federal case wasn’t just significant because Skelos was arguably the most powerful politician on LI and the fifth-consecutive state Senate leader to be indicted. It was also unprecedented because his trial occurred at the same time that his former counterpart, ex-state Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver (D-Manhattan), was on trial in an adjacent courthouse for similar but unrelated corruption charges. Skelos and Silver were two of the so-called three men in a room—the third being Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat—that set the state’s legislative and budget agenda.

Although the governor wasn’t on trial, his personality became part of the testimony nearly as often as those of Silver and Skelos at both trials. Preet Bharara, U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, who personally watched the trials some days, issued a statement early in January saying there was insufficient evidence “absent any additional proof that may develop” to file charges in his investigation into whether Cuomo’s staff interfered with the governor’s Moreland Commission on Public Corruption, which the governor prematurely disbanded two years ago.

In making the case against the Skeloses, Dorego testified that if Glenwood was being forced to pay the son of a senator whom they donated to and lobbied, he decided the company’s executives should distance themselves from the payments to Adam. So, Dorego devised a plan to have a business associate’s company give Adam a $20,000 referral commission check for title insurance work that Adam neither referred nor performed. And Dorego got Adam a job as a consultant at AbTech Industries, an Arizona-based water filtration company in which the Litwin family invested—even though Adam’s lone qualification was his last name.

“When I heard about it, I was like, well, I literally know nothing about water or any of that stuff,” Adam later told an AbTech official who was wearing a wire for the FBI, according to a recording of the conversation played in court. But just as Nassau County was considering an Adam-assisted bid by AbTech on a $12-million stormwater filtering project in 2013, Adam, through Dorego, extorted the company to more than double his pay under the threat of blocking the contract’s approval. Adam was at AbTech for only several months when he made the demand.

Before that raise came up, Adam was making $230,000 in 2011 through his title insurance work, his consulting work at East Coast Power & Gas and through his own firm, Rockville Strategies. But throughout 2012, his father repeatedly told Dean’s longtime friend, 57-year-old Anthony Bonomo of Manhasset, that Adam was broke and needed a job with benefits like those at Bonomo’s medical malpractice firm, Roslyn-based Physicians Reciprocal Insurers (PRI). In 2013, Bonomo gave Adam a job as an insurance salesman paying $78,000 annually, but he was a no show. Because Bonomo, PRI’s chief executive officer, also lobbied the senator for legislation critical to his company’s survival, Bonomo was reluctant to fire Adam for fear of “having a problem in Albany,” he testified.

Defense attorneys for the Skeloses, who face up to 20 years in prison when they’re scheduled to be sentenced on April 4, filed a motion last month asking a judge to set aside the conviction and grant a new trial. During the court case, they had argued that the testimony of four key witnesses—including Dorego, Bonomo and two AbTech execs—was tainted by their signing non-prosecution agreements.

Adam’s attorney, Christopher Conniff, said the only thing his client is guilty of is saying “some things he shouldn’t have in order to get a job.” Dean’s attorney, Robert Gage, said during opening and closing statements that “there is no quid pro quo” because the senator never changed his positions on a bill in exchange for money.

Tatiana Martins, one of three prosecutors who tried the case, put it this way in her opening remarks: “From a corrupt politician’s scenario, there’s nothing better than getting bribed for something you would have done anyway.” Jason Masimore, the lead prosecutor trying the case, likened Adam using his dad’s clout to get paid to the boy in Where the Sidewalk Ends marveling at how nice everyone is to him when brings his gorilla to school.

“The gorilla in this case is the power of the office of the Senate majority leader,” said Masimore.

HELL BREAKING LOOSE

To understand why Glenwood executives were so eager to have Republicans regain the state Senate majority with then-Sen. Skelos as their leader, jurors in Manhattan heard a brief history of the Albany chamber’s power structure.

For the first time in decades, Democrats won control of the state Senate during the 2009-2010 session. Since New York is a liberal stronghold, Democrats have long had a majority in the state Assembly, the other legislative chamber, and usually hold the three statewide offices, which includes the governor, the attorney general and the comptroller. The GOP-led state Senate had often been the only check on Democratic control of all other branches of state government.

Amid the dog days of summer 2010, as the Democrats’ two-year reign over the state Senate began to wane, Dorego emailed a colleague at Glenwood to express concern about a bill that would return rent control regulation from the state to New York City—a proposal that Glenwood officials referred to as “the atomic bomb,” Dorego testified.

“Albany. All hell breaking loose,” Dorego frantically wrote to his colleague on Aug. 3, 2010, according to evidence showed in court, as state Sen. Liz Krueger (D-Manhattan) had begun “moving bad bills to the floor…. They don’t have the votes but terrible precedent giving those bills credibility.”

Krueger was leading the charge on legislation that would repeal what’s known as the Urstadt Law, passed in 1971, which essentially prohibits municipalities—including New York City—from enacting stricter rent control laws than the state’s.

“The Urstadt Law is an unconscionable restriction on the democratic home rule of New York City residents,” Krueger said in 2006, one of the many times she’s proposed the pro-tenant bill. “It restricts our ability to control our policy and our destiny on a strictly local issue.”

Similar legislation has repeatedly passed the Democratic-led Assembly. But when the pro-landlord Republicans ran the state Senate, the bill never came up for a vote there, so it never had a chance of reaching the governor’s desk to be signed into law. Real estate officials testified that the close call on a repeal of the Urstadt Law motivated executives, landlords and developers to increase their campaign donations to the most competitive state Senate races that were their best bets at helping the GOP regain a majority, starting in 2011.

“The man doesn’t panic, but he was very concerned,” Dorego testified of Litwin, who “would tell anyone within earshot that a Republican Senate was the most important thing on the agenda.”

They tried to close the deal in a three-word email. “Dean needs money,” Richard Runes, a Glenwood lobbyist, emailed Dorego on Oct. 25, 2010, a week before that year’s elections. His message was titled simply “SRCC,” the abbreviation for the Senate Republican Campaign Committee, which gives millions of dollars to GOP state Senate candidates. Dorego knew that Runes was referring to then-Sen. Skelos, a central figure in the SRCC.

It worked. Following a dramatic recount that lasted a month after Election Day, then-Mineola Mayor Jack Martins unseated state Sen. Craig Johnson (D-Port Washington), handing the Republicans the slim 32-30 majority they needed to regain control of the chamber. But the win later cost Glenwood more than just campaign donations, court testimony revealed.

PERSISTENCE PAYS

Despite Litwin telling Dorego to ignore Dean’s request during their celebratory December 2010 meeting, Dorego was directed to meet with Adam two months later.

Dorego testified that he was told not to make any commitments to Adam because of the “uncomfortable position” it might put them in. On Feb. 17, 2011, they met at Paramount Tower, a Glenwood property in Manhattan, and Adam pitched Dorego on getting energy consulting services, not title insurance work as Dorego had expected.

“I was hoping it would just go away,” Dorego testified. But Adam, who appeared overly eager for Glenwood to hire his company for energy consulting, later sent a slew of follow-up emails to Dorego.

At the same time that the son was pressing Dorego for work, Glenwood was lobbying the father for not only the rent control law renewal, but also renewal of the 421-a tax abatement program, a state law giving developers such as Glenwood a decade-long break on paying property taxes on multi-residential housing they build. The tax break had lapsed a month before Adam and Dorego’s meeting. Tenant advocates rallied last year against the law at Dean’ office, saying the program’s other intent, building affordable housing, was subverted into becoming a favor factory for wealthy campaign donors. To the contrary, Dorego described the tax breaks as essential to development.

“It’s absolutely necessary,” Dorego testified of Glenwood’s reliance on 421-a, adding that without the tax breaks, “it doesn’t make economic sense to build a building.”

Around the time 421-a lapsed in early 2011, Glenwood had purchased a plot at the corner of West 62nd Street and Amsterdam Avenue in Manhattan, across the street from Lincoln Center on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Dorego testified that Glenwood needed Dean’s help renewing 421-a before they could break ground on construction. When the stalemate ended, Glenwood eventually built a 54-story luxury apartment building dubbed Hawthorn Park. But before that tower went up, Litwin was worried that the 421-a law might not get renewed, putting the $125 million his company had spent on the land at risk.

“[Litwin] actually thought that 421-a was in jeopardy because of the Assembly,” testified Joseph Strasburg, president of the Rent Stabilization Association, a New York City business group that represents landlords. Strasburg said he was unable to convince Litwin that 421-a was safe.

But before Strasburg was proven correct, Dean met with Dorego and other real estate industry leaders several more times to hash out state Senate negotiations on the legislation. During a meeting on March 18, 2011, one month after Dorego had met with Adam, Dean “reiterated that it would be great if we could find something for [Adam] to do.” By May of that year, during another meeting about the real estate laws, Dorego told Dean about the lawyer’s idea to get Adam a job at AbTech.

A month later, the Rent Act of 2011 passed the state Legislature on June 24, 2011. Later the same day, Cuomo signed it into law. Gage, Dean’s attorney, noted that Dorego hadn’t actually done anything for Adam by this time, and if 421-a hadn’t been renewed, it would have had significant impact on new development in New York.

Regardless, in the year that followed, Adam continued emailing—and Dean kept pressuring—Dorego to get Adam work. At Chadwicks American Chophouse & Bar in Rockville Centre on Nov. 15, 2011 Dean “told [Dorego] a little more about Adam’s struggles,” Dorego testified.

Adding to Dorego’s concerns were Dean’s flashes of anger. Aside from the then-senator yelling at Dorego for donating to Democrats’ campaigns, Dorego recalled how on Feb. 8, 2012, Dean lost his temper with landlords affiliated with the Real Estate Board of New York, a business group that the senator felt wasn’t appreciative enough of the then-majority leader’s legislative efforts, Dorego recalled. The officials included developers Bruce Beal and Stephen Ross, the billionaire owner of the Miami Dolphins, who Skelos told that “if at some point they don’t pony up he was gonna ‘F’ them,” Dorego later testified.

By “pony up,” Dean meant donate to political campaigns to keep the Republicans in control of the state Senate, Dorego explained. U.S. District Court Judge Kimba Wood denied prosecutors’ request to ask Dorego if Skelos had meant he would “F” the men “physically or some other way.”

But the same day as his father’s heated meeting in February 2012, Adam sent Dorego yet another email about trying to sell energy consulting services to Glenwood, according to evidence presented in court. Dorego testified that he was “fed up” with Adam’s emails yet scared of Dean’s ability to hurt Glenwood legislatively if the senator wanted.

“I was afraid that they were going to get angry at us for not responding,” Dorego testified.

During a meeting at Porter House, an upscale steakhouse in Manhattan’s Columbus Circle in April 2012, Dean asked Dorego again “if there was something we could do for Adam.” When Dorego reminded Dean that Dorego was getting Adam a job at AbTech, the senator was dismissive, saying Adam needed something more immediate. After a meeting in July, Dean—once again—told Dorego that his son “needs help.” Dorego testified that the requests were becoming a nuisance.

“I just felt like we were being a bit badgered at this point,” Dorego told the courtroom.

MUDDY WATERS

As his requests turned to nagging and summer turned to fall in 2012, Adam finally did start working as a consultant for AbTech, but he evidently got off to a stormy start.

“There is great potential for [Adam] to exploit his father’s contacts statewide,” Dorego, who also represented the Litwin family’s $2 million investment in AbTech, told Glenn Rink, the filtration company’s 56-year-old founding chief executive officer in a July 31, 2012 email. Dorego had introduced Rink and Adam via email. Two weeks later, Adam met face to face with Bjornulf White, then-AbTech vice president, at W Hotel in Manhattan, leaving White “pleasantly surprised,” he testified.

By this time, Adam had already spoken to Town of Oyster Bay officials, according to court testimony, about the possibility of installing AbTech’s “smart sponge” filters in stormwater runoff drainpipes to prevent pollutants from washing into the bays after rain storms. Around the same time, Dean started forwarding Adam emails with links to news articles about stormwater issues, which Adam forwarded to Dorego to show he was doing his homework.

Simultaneously, the then-senator also told Bonomo, the CEO of PRI, that Adam needed a job with health benefits when Dean and Bonomo saw one another at the SRCC’s annual fundraiser at the Saratoga Race Course on Aug. 22, 2012. That prompted Bonomo to offer Adam a job at PRI when Bonomo later saw him at the same event. Neither Dean nor Adam mentioned Adam’s other employment, which earned Adam—who New York Post reporters spied wearing $1,000 suits during the trial—and his wife $272,000 that year, according to court testimony.

Back on the AbTech front, Dorego became involved in negotiating Adam’s contract, calling it “ludicrous” and questioning the legality of proposing to pay Adam for lobbying counties on a contingent fee basis, according to a Sept. 6, 2012 email shown in court. A week later, Adam emailed Rink, saying that he canceled a scheduled meeting with Chief Deputy Nassau County Executive Rob Walker because Adam’s AbTech contract “hasn’t been worked out yet,” evidence showed.

Adam’s work at AbTech was temporarily shelved. That is, until Superstorm Sandy rolled ashore a month later and AbTech, joining the ranks of storm-chasing contractors, called on Adam to help get municipalities to include smart sponges in their recovery aid requests while the federal disaster funds were flowing, according to court testimony.

MONEY FOR NOTHING

During the calm before the storm, while Adam’s AbTech work was on hold pending a resolution to the contract dispute, the third leg of the conspiracy started to take shape.

Dorego emailed Adam on Sept. 25, 2012 to ask: “Who do you write title insurance for?” In his reply the same day, Adam said: “If you have a title for me… I could really use the work if you have anything for me, it’s been a real slow year in the title world.”

Adam later forwarded the email to his father and added: “I still haven’t heard anything back.” Dean replied: “Following up. Be patient.” Prosecutors said later in court that phone records showed the senator had called a Glenwood lobbyist minutes before writing that reply to his son.

Nine days after that exchange, Dorego met with Dean, Litwin and other real estate types. Hours later, Dorego called then-North Hempstead Town Councilman Tom Dwyer (D-Great Neck), who is in the title insurance business. Dorego asked Dwyer if the councilman could “share a piece of a referral” with Adam, Dorego testified.

“I said there was a lot of pressure being put on me by [Adam] and his father…to give him a piece of business,” Dorego testified.

“Charlie wanted me to make a payment to Adam,” Dwyer testified later in the trial. “Charlie did not want the payment to Adam to be associated with Glenwood Management.”

That meant Dwyer would have to make the payment through American Land Services (ALS), where he is chief operating officer, instead of his other company, American Land Abstract (ALA), which he co-owns with Steve Swarzman, Litwin’s grandson. And since Glenwood was ALA’s main client, to the tune of $200 million annually, Dwyer testified that he did what Dorego asked for fear of upsetting his biggest cash cow.

“There was a transaction coming up later in the year that wasn’t associated with Glenwood, and we took a percent of the transaction,” Dwyer testified. “We wanted it to be associated with a transaction…so that it wouldn’t just be a payment out of a bank account.”

That is, they were eager to make the payment look legitimate. So eager, Dwyer admitted on the stand, that he initially lied to federal investigators and said that ALS’ payment to Adam was an “incentive bonus.” Days later, he came clean and turned over key evidence to the FBI.

“I was extremely nervous,” said Dwyer, who stepped down as councilman in November 2013 after serving 11 years in public office to “take on a new role in the private sector,” he said in a statement at the time. About his lying to the feds, he told the court: “I made a big mistake.”

The key evidence Dwyer turned over included an email dated Oct. 20, 2012 with the subject line “Adam’s 10%,” in which Dwyer asked Dorego how Adam’s payment was calculated. Dorego testified that he was concerned with the number of people cc’d on the email when he replied “not for emails.” Dwyer said that Dorego later called him to emphasize the point.

“When you write ‘not for emails,’ it’s because ultimately you don’t want it to turn up in a case like this, right?” Conniff, Adam’s attorney, asked Dorego during cross examination. Dorego agreed.

“It concerned me that we were giving business to the senator’s son,” Dorego testified. “I didn’t think we were doing anything wrong, but I thought the senator might.”

Five months later—by which time Adam was working at AbTech and PRI—Dwyer said he met Adam for lunch at Coolfish in Syosset, where he gave the senator’s son an envelope containing the $20,000 check without discussing its contents.

“This should get Dean off my back,” Dorego said to Dwyer after the ex-councilman told the Glenwood attorney that Adam was paid, Dwyer testified.

EYE OF THE STORM

Thousands homeless. Gas shortages sparking chaos. Raw sewage spilling into waterways. Ninety percent of Long Island blacked out. Two barrier islands breached in three spots. Curfews in effect for the most devastated areas.

Amid the catastrophe unfolding on LI after Sandy hit on Oct. 29, 2012, AbTech saw an opportunity. The company was eager to pitch their stormwater filters to municipalities at the start of the infrastructure rebuilding. With all the federal Sandy aid flowing to the region, AbTech hoped localities would have the money to spend.

“It drew a lot of attention to the stormwater issue,” testified White, the then-AbTech exec who met Adam over the summer.

Eleven days after the storm hit and two months after Adam’s contract negotiations stalled, White emailed Adam urging Dean’s son to start pitching AbTech’s smart sponges to Nassau and Suffolk county officials. AbTech had heard there was a three-week deadline for localities to apply for Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) storm recovery funds, according to court testimony.

The next day, Adam replied to White saying that he had a phone conference set up with management staff at the Nassau County Department of Public Works (DPW), according to emails shown in court. At the time, the agency was in crisis mode trying to make emergency repairs to Bay Park Sewage Treatment Plant, which failed during the storm, flooding homes and waterways with human waste.

“Any word on Suffolk?” Adam wrote in another email that day to Thomas Locascio, director of operations for the then-senator’s district office. Locascio replied: “One step at a time. Hah. Your dad prob needs to make a call.”

Less than a month after Sandy hit, Adam’s contract dispute was resolved, evidence showed. He signed a two-year consulting deal for AbTech to pay him $4,000 monthly, which would be increased to $5,000 monthly upon execution of the first contract and then $10,000 monthly once Adam landed six contracts for AbTech with a total value of $500,000 or more, according to evidence presented in court.

A week later, Adam emailed Dorego to say that he believed the Nassau contract would “be included in the FIMA recovery package” and that the county would issue a Request For Proposals (RFP)—the process in which companies compete for a chance to secure government contracts.

Adam told White that Adam’s “main contact” would be Walker, Nassau’s chief deputy county executive, and said the RFP would be issued within 10 business days of Nov. 26, 2012. But, despite Adam’s assurances, months went by before the county issued its request. White testified he was on a conference call with Nassau DPW officials about the RFP on Christmas Eve of that year.

“They said it was for the purpose of drafting the RFP and to make sure they were doing it right,” White testified.

SENATOR POTHOLE AND THE NO SHOW

As Adam’s consulting for AbTech got underway, so did the holiday season, giving Dean another chance to suggest that Bonomo hire Adam at the CEO’s company.

“Festive attire” was noted in Dean’s schedule for Dec. 5, 2012, when he attended the annual holiday party hosted by ex-U.S. Sen. Alfonse D’Amato (R-NY), 78, at Brass Monkey, a pub in Manhattan’s trendy Meatpacking District. It was there that Dean reiterated to Bonomo that Adam needed a job. Bonomo told Skelos that Adam hadn’t taken the CEO up on his prior offer. A week later, Adam filled out an application at PRI, but omitted in his work history his employment at AbTech and East Coast Abstract, evidence showed.

“You know who I am, right?” Adam asked his new boss, Chris Curcio of Floral Park, vice president of sales and marketing at PRI. It was Adam’s first day as a medical malpractice insurance sales trainee on Jan. 2, 2013. Curcio later told the court that he felt a “sense of entitlement and arrogance” from Skelos’ son. Adam told Curcio that his dad had a special arrangement with Bonomo, Curcio’s uncle, that allowed Adam to only work two days per week.

Curcio said he was “taken aback,” but didn’t question his uncle about it. Bonomo testified that there was no such arrangement. Curcio said Bonomo had previously told Curcio that the CEO “was helping a friend” by hiring Adam.

According to Curcio’s testimony, Adam left work early his first day, didn’t show up the next day and then on Friday, came in for one hour, and filled out a time sheet indicating that he had worked 35 hours—including New Year’s Day, when the office was closed, and New Year’s Eve. His official start date was Jan. 2, according to a letter PRI sent Adam.

“Some days he was there, some days he wasn’t; he would leave work early other days,” Curcio testified. “I thought it was unusual… it’s a new job and you have to work for time off.”

Perturbed with his new hire’s behavior, Curcio started keeping a handwritten log of Adam’s comings and goings. Shown in court, the entries for most dates on the log included the phrase “no show.”

“It was getting repetitive,” Curcio said when asked in court why he had stopped keeping track four months after Adam started.

“I have other jobs, and my dad has an arrangement with Anthony,” Adam said after Curcio confronted him.

Ten days after Adam started, Dean called Bonomo to complain about Adam’s boss.

“He was upset that he had received a call from Adam,” Bonomo testified that Dean told him. “His supervisor was giving him a hard time, picking on him.”

Bonomo hadn’t heard about that problem, the CEO testified, so he checked with Curcio. Curcio explained that Adam wasn’t showing up to work. Bonomo called the then-senator back to relay the message that the problem was with Adam, not Curcio.

“Just work this out,” Dean told the CEO, Bonomo testified.

Bonomo turned a blind eye to Adam’s failure to show up. That’s because his company, the second-largest medical malpractice insurer in the state, pays four lobbying firms a total of $300,000 annually to negotiate with the likes of then-Sen. Skelos on so-called budget extenders—legislation that requires regular renewals and is critical to PRI’s existence in the heavily regulated industry, the CEO told the court.

“I did not want to have a problem in Albany,” testified Bonomo.

“If this was going to be a problem, I didn’t want this this to get in the way of passing legislation.” – Bonomo

Martins, the prosecutor, asked Bonomo: “If he had been any other employee who had not been showing up for work…would you have continued paying him?” “No,” came Bonomo’s reply.

Selling medical malpractice insurance requires taking a 99-hour course, passing an exam and securing a state-issued license. It’s not a job for a no show. Adam took the class, but failed the test repeatedly, according to court testimony. When Curcio asked Adam about his license status, he didn’t get a response, Curcio testified.

By June of 2013, when Adam was due for his six-month review, a perplexed Curcio asked his supervisors what to do with Adam’s survey. Bonomo replied, “Do nothing,” according to emails read in court.

But lobbyists at Park Strategies, a lobbying firm founded by D’Amato, grew increasingly concerned with Adam’s employment at the company after PRI had become one of their clients. Gregory Serio, the lobbyist who handled PRI’s account, repeatedly told Bonomo that hiring Adam was a problem.

“He did not think it was a good idea,” Bonomo said Serio, the former state Superintendent of Insurance, told him. “He thought that it could be detrimental to their lobbying efforts in Albany.”

D’Amato—who got his nickname “Senator Pothole” for his getting involved in hyperlocal issues during his tenure in the U.S. Senate—took it on himself. That spring, Al met Dean at the then-majority leader’s office to discuss the problem, but Skelos was unphased, D’Amato said in court.

“He told me that Adam really needed the job,” D’Amato testified.

Then Dean asked Al to meet with Adam. One meeting led to another, and Adam expressed interest in working with Park Strategies, but the discussions went nowhere fast, the former Senator recalled.

D’Amato said his staff was “forcefully” opposed to working with Adam, whom D’Amato warned may need to register as a lobbyist to perform some of the activities that Adam did for his clients.

“The appearance of impropriety was such that we could not work together,” testified D’Amato, adding that it “would bring great questions about conflicts.”

D’Amato’s testimony was triply ironic. Aside from D’Amato’s holiday party helping facilitate Adam’s PRI job and irking Park Strategies lobbyists, it was notable that D’Amato—who has a reputation for ethical lapses—expressed reservations about working with Skelos’ son. Most curious of all was D’Amato’s testifying before Judge Wood, a Democrat, whom D’Amato, a Republican, had nominated to the bench in 1987 while remarking on her beauty during the Senate proceeding.

Meanwhile, at PRI in 2013, Curcio finally told Adam it wasn’t “working out,” prompting what Curcio later described as a “blow out.” He didn’t recall the date the “choice words” were exchanged over the phone.

“Guys like you aren’t fit to shine my shoes,” Adam told his boss, Curcio testified. “And if you talk to me like that again, I’ll smash your fucking head in.”

After that conversation, Bonomo asked Dean for permission to demote Adam to a stay-at-home telemarketing consultant who would call 100 doctors’ offices weekly to generate sales leads and earn $36,000 starting that fall. This solution, the CEO testified, would allow the company “to alleviate the problem but not have to worry about any ramifications.” Dean approved of the arrangement, but Adam only called about 15 offices per week. Whether he worked in the office or from home, Adam did not help PRI insure one new client, Curcio testified.

“It’s my effing money and I can do what I want with it,” Bonomo told his brother when he was asked why he paid Adam despite his failure to work, a rationale defense attorneys later had the CEO confirm in court.

As it turned out, Bonomo’s problem in Albany was unavoidable. Aside from leading PRI, he was also chairman of the New York Racing Association (NYRA), the agency that oversees horse racing in the state—until he wound up being a witness at his friend’s trial.

“I took a leave of absence with the advent of this litigation,” Bonomo testified of his role at NYRA.

STRONG-ARM EXTORTION

Three months after Adam had said that Nassau would issue an RFP in response to AbTech’s unsolicited bid for a stormwater filtration project, a request for devices the company provides went public, evidence showed.

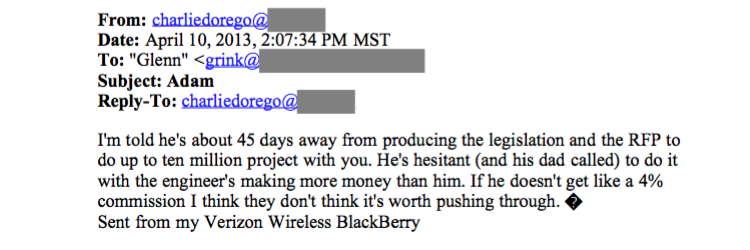

On April Fool’s Day 2013, AbTech’s White asked Adam to hand deliver the company’s bid to Nassau DPW officials before the RFP’s deadline that week. Days later—and two days before D’Amato met with Dean about Adam not showing up to work at PRI—Dorego sent an email to Rink, AbTech’s CEO, saying their new consultant was demanding he get a raise or the Skeloses would block the company’s proposed Nassau contract. The young Skelos was evidently miffed.

“[Adam]’s hesitant (and his dad called) to do it with the engineer’s making more money than him,” Dorego wrote in the April 10, 2013 email. “If he doesn’t get like a 4 percent commission, I think they don’t think it’s worth pushing through.”

Four percent of what was said to be a $12-million contract is $480,000. On the stand, Dorego explained that a “furious” Adam had told Dorego that the then-senator called Adam, not Dorego personally—a distinction that the defense grilled Dorego about. Dorego later said that he shouldn’t have sent the email, but he was under pressure because he had the impression that Adam and Dean “were gonna stop whatever they were doing” for AbTech, Dorego told the court.

“I can’t believe he’s going to try and hold us hostage to renegotiate the contract,” White replied to Rink in an email read in court. “The engineers are getting paid for labor hours to do real work. I think around 5,000 manhours. Unreal.”

White testified that his relationship with Rink was never the same after that, because Rink subsequently compromised and gave Adam a raise to $10,000 monthly, despite White’s disapproval.

“I saw it could be a death threat to our entire projects in this area,” said Rink, referring to the email, which he called game changing. “I did not believe I had any choice.”

White had also recognized the looming menace.

“I thought he meant it was basically a threat to interfere with the process and hurt AbTech’s chances,” White testified, “through contact between the senator and [Nassau County Executive] Ed Mangano in a way that would be detrimental to AbTech.”

Dorego told Rink that “if AbTech takes care of Adam, his father will take care of AbTech,” White told the court.

After the demand was made, Adam emailed White to say that he left two messages with Nassau DPW Commissioner Sheila Shah, but she hadn’t called back.

“Will have my father call Ed this Thursday if I don’t hear back from her tomorrow,” Adam wrote in an April 30, 2013 email read in court.

Three months later, after AbTech was named the winning bidder on the RFP, the Nassau County Legislature approved the contract and Adam’s raise kicked in. At around the same time, during a meeting in July 2013, Adam told Dorego that he wanted to get Rink off AbTech’s board and take over the company, Dorego testified.

That fall, the Nassau Interim Finance Authority (NIFA), the state board that controls the cash-strapped county’s finances, didn’t bring up the contract for a vote and let the time they had to act on it expire—in effect, automatically approving AbTech’s multi-million deal. Then the company turned its sights on starting the project and lobbying for passage of state legislation required for them to finish it.

AbTech had to take this two-pronged approach because under state law, separate companies are required to design and build public works projects. AbTech wanted then-Sen. Skelos’ help getting a so-called design-build bill approved in Albany to let the company do both aspects. It was imperative to AbTech’s bottom line, since the first two phases of the contract were for a combined estimate of $331,000—a fraction of the multi-million-dollar construction leg of the job, which would go to another contractor if the bill wasn’t passed.

“It did not proceed smoothly,” White testified.

By coincidence, the month Mangano signed the AbTech contract, Rink bumped into Dean in the elevator of a Sheraton Hotel in Manhattan, where they both happened to be on Oct. 23, 2013. It was the first time the two had met. Rink told Skelos that he worked with Adam, but Dean didn’t acknowledge the remark before they shook hands and parted ways.

“It was awkward,” Rink recalled in court.

DIALING FOR FRACKING

On Halloween 2013, Adam introduced White to his dad at the then-senator’s office, where Dean asked White about AbTech’s filters that clean wastewater resulting from hydraulic fracturing, the controversial gas-drilling practice known as fracking, White later testified.

Three months after that meeting, Adam emailed a link to AbTech’s frack filter website to Robert Mujica, the senator’s then-chief of staff, who forwarded it to Elizabeth Garvey, counsel to Skelos and the state Senate GOP majority. Days later, in January 2014, Garvey emailed James Clancy, then-assistant commissioner of the state Department of Health, to ask who was conducting the technical review under Cuomo’s fracking moratorium that was in effect at the time.

“Find it curious that senate Republican is reaching out to me directly,” Clancy wrote in an email to his colleagues. “Thoughts on a response?”

Concerned about the potentially controversial request, Clancy forwarded the email to the governor’s staff saying: “this is a biggie” and asked how to handle it. They later determined that it “sounded legit,” but Clancy would sit in on the meeting to ensure that AbTech didn’t ask anything inappropriate, such as inquiring about the moratorium, according to court testimony.

The topic was important because one of the issues then being debated in Albany was whether fracking wastewater would be trucked from the well sites—clogging upstate roads with countless big rigs—or recycled on-site using filters such as those made by AbTech. In May 2014, the company got their meeting to pitch health department officials and it went off without Clancy having to shut it down.

In court, prosecutors argued that Dean’s staff setting up a meeting for his son’s employer proved then-Sen. Skelos was using his power for his son’s gain. That’s because if fracking were approved in New York, Adam potentially stood to earn a lot more money by selling AbTech’s frack filters in addition to the stormwater filters.

When Garvey took the stand, she testified that Dean never disclosed Adam’s ties to AbTech in their conversations. Kelly Cummings, spokeswoman for the state Senate’s GOP majority, also testified that ex-Sen. Skelos never disclosed his son’s AbTech job to her, either.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g6oM3b5PGpY

DOWN THE DRAIN

Shortly after AbTech’s meeting with the state health department and a month before they got their first payment from Nassau—$54,602 in June 2014—the deal was starting to crack just as County Executive Mangano was touting it.

In May, Timothy Kelly, a Nassau DPW official, emailed White to say that the AbTech contract was for “$331,625, not $12 million,” according to emails shown in court. “The original contract amount is only enough for site selection, the rest needs to come from grants,” Kelly wrote.

“I would not go by his reading of the contract,” testified White, who disagreed with Kelly’s assessment.

But during a Nassau news conference two months later announcing the AbTech contract, which White attended, Mangano said that only one outfall pipe would be fitted with the smart sponge filter as part of a “pilot program.” Up until that point, AbTech had interpreted the contract to be for installing filters on a dozen stormwater pipes right away.

“Additional outfall pipes will be outfitted as federal funds become available to help support this project,” Mangano told reporters on July 8, 2014 at his office in Mineola. “In the interim, we’ll be monitoring the success” of the one.

A month later, White met with Adam, DPW officials and Walker, who told White that the county only had $400,000 to install the filter on one outfall pipe, not $12 million to do a dozen as AbTech had thought. Nassau officials estimated it would cost about $2 billion to install the technology at all 2,600 stormwater outfall pipes countywide, according to trial testimony.

“I told him [Walker] that I’m not comfortable with this random number,” White testified. “This was sort of backwards. They were just throwing out a number, and I had no idea if it would cover the cost.”

Installing smart sponges involves excavating the ground near a stormwater pipe’s outfall, which empty into creeks and bays on Long Island. Once the hole is dug, crews cut out a section of the concrete pipe and install a concrete vault containing the plastic cartridges known as smart sponges, which filter pollutants from stormwater passing through it. Maintenance requires regular replacement of the cartridges, which are incinerated once they’re used up.

Six months after Mangano’s AbTech press conference, Adam sent White a link to a story about Nassau funding a $12-million Glen Cove sewer project.

“This infuriates me,” White replied, noting how it was the same amount that he believed the county had misled AbTech about.

Defense attorneys repeatedly argued that Adam was only helping AbTech solve a serious problem on LI. Stormwater runoff flows through drainage pipes without being filtered through sewage treatment plants every time it rains. Local waterways are in turn polluted when stormwater flushes in tainted with petroleum products left by vehicles on streets, fertilizers sprinkled on lawns and other pollutants. Stormwater runoff leads to excess nitrogen in waterways, which causes local bays to suffer annual algae blooms such as brown tide, one of the major factors that gravely hurt the shellfishing industry on LI.

“It was a product that met a legitimate need,” said Gage, Dean’s attorney, in court.

Adam’s attorney noted that AbTech had previously hired other consultants to help land government contracts.

“AbTech hired Adam for a completely legitimate reason,” Conniff said. “They wanted to take advantage of Adam” because he “could open doors.”

Prosecutors did not deny the legitimate need for stormwater filtration on LI. Babylon and Sag Harbor have adopted the technology, plus AbTech counts clients in six states nationwide. After Rink gave jurors a courtroom demonstration, prosecutors noted for the record that the dirty water had come out clean after it was filtered through a sample of AbTech’s smart sponge.

What was a crime, the prosecutors argued in court, was that the senator and son extorted AbTech into hiring Adam and more than doubling his pay under the threat of killing the company’s chances at landing what was thought to be its largest contract ever.

Since the scandal broke, the company has taken a hit. Rink, AbTech’s CEO, said that its stocks are now valued at 3 cents per share, down from a high of $1.45. Already a self-described tough sell, AbTech’s prospects are far fewer now.

“We’re barely allowed to operate anything in New York,” Rink testified.

By December 2014, federal prosecutors had convinced a judge to authorize the FBI to wiretap Adam and Dean’s phones, producing the spiciest evidence: recordings of them discussing their schemes.

“I’m going into the city to meet with some billionaires…on school tax credit stuff,” the senator told his son in one call on Dec. 8, 2014. Adam replied: “Dad… you’ve gotta take these names down for me. All I need is contacts. I’ll take care of the rest.”

Two days later, a storm caused severe flooding on LI, and Adam was recorded laughing about the damage with his father because it would help him sell AbTech filters.

“We got some major water problems here with all the flooding going on… I love it! Keep it coming Mother Nature! Keep it coming!” Adam rejoiced to his father in a wiretapped phone conversation on Dec. 10 of that year, according to the wiretaps. Dean replied: “It will.”

Soon, as the prosecution showed, the evidence gathered in the recordings really started to pile up, showing Adam and his father exploiting the senator’s power for his son’s personal financial gain.

“My father sat with Ed two weeks ago,” Adam told White on Dec. 14 of that year, referring to a meeting between the senator and the Nassau county executive. “Ed promised it’d be done and they’d find the funding for it.”

White, frustrated by the lack of payment—even the $400,000 Walker said was coming—replied: “It’s like they’re playing games with us.”

Days later, the frustrations grew when Gov. Cuomo announced his decision to ban fracking in the state, killing Adam’s prospects of selling AbTech’s frack filters upstate.

“Argh, this day sucks!” Adam told his father following the much-anticipated announcement on Dec. 17, 2014. “It does,” his dad replied, “but we’re totally gonna focus on the other thing now.”

During the same call, Adam urged his father to run for governor and unseat Cuomo. Dean sounded like he was entertaining the idea. The powerful Republican told his son: “No more buddy buddy, he’s full of shit.”

Later that same day, Adam called Rink to let the AbTech CEO know that he had set up meetings with officials from the Town of Hempstead and the Village of Freeport, who had FEMA aid coming to them after Sandy.

“We’re gonna tell them what to spend it on,” Adam told Rink.

A day later, Adam texted Walker: “Need Tim Kelly to release the 400K…all work is done. Says he’s just waiting on his supervisor’s approval.”

Walker didn’t reply. But the next day, Adam called White to say Mangano told him the money was coming.

“It’s like he had no idea what the project was even fucking about,” Adam told White in the recorded call. “It’s like, you had a press conference about it three months ago.”

Just days after that came the infamous “Greek diner call” in which Adam berated Demetrios Raptis, the head of a Greek diner association group, for not taking Adam up on an offer to meet.

“You have my cellphone number….It’s a privilege to have that number,” Adam told Raptis in the call, according to the wiretap recordings. “Now, if you want to utilize my fucking reach and business opportunity, then you call me and I’ll set up a meeting. Otherwise, don’t tell me you’re going to set up a meeting and not set it up. Okay?”

As the argumentative conversation escalated, Adam withdrew his offer.

“You had an opportunity to work with someone who could get a lot of things done for you, but now it’s done,” Adam said, prompting Raptis to ask him what the offer was. “It’s done. I’m not going to go there.

“I’m not going to say this on the phone,” Adam said. “You could have heard those opportunities in person, but you wanted to not do that. For some reason, you thought you were more important and more powerful because you have a few members that, that have diners. Okay. Who gives a shit about diners?”

Back on the AbTech front, by New Year’s Eve, the company was continuing to complain to Adam about not getting paid by the county. Adam indicated that his father could punish Nassau, evidence showed. Walker later testified he feared the same thing.

“Nassau County, man. Burning bridges left and right,” Adam told White in the Dec. 31, 2014 wiretap. “I tell you this, the state is not going to do a fucking thing for the county. Any favor that [Mangano] calls and asks for, it’s not happening.”

White asked: “What’s not happening?”

Adam continued: “Like [Mangano] will call and ask for favors to help with NIFA or to help with the labor unions and negotiating contracts or this and that, and it’s just not going to happen after they haven’t helped us with what we needed.”

Two days later, Adam angrily called his father after reading a newspaper report that Nassau was paying another company $57.4 million per year for 20 years in a public-private partnership to run sewage facilities—while Nassau was behind in paying AbTech, according to court testimony.

The next day, Dean called Mangano to make arrangements to ride together to the wake of Wenjian Liu, a New York City police officer killed in the line of duty. During that call, the then-senator pressed the county exec to explain why Nassau was entering into a new sewage contract but wasn’t paying AbTech.

In a wiretap of that call played in court, Dean asked Mangano: “Where does that leave the other situation?” Prosecutors said that “situation” was AbTech. Mangano fumbled for a reply.

“It just leaves the funding, which doesn’t come from them,” Mangano said on the wiretap. “It doesn’t come from that. The funding’s supposed to come from either FEMA or…”

Dean cut Mangano off and said: “Somebody feels like they’re just getting jerked around the last two years.” Mangano replied that they’d talk about it the following day. “Somebody” was code for Adam, prosecutors told the jurors.

“I spoke to that guy and he says that’s not gonna affect what you’ve been doing,” then-Sen. Skelos told his son, according to anther wiretap played in court. Adam, who doubted what Mangano told Dean, shot back: “You need to stop listening to that guy.”

THE FUNERAL

A federal investigator had Mangano’s black SUV under surveillance when the vehicle picked up Dean on Jan. 4, 2015, and the agent followed it on the Southern State Parkway.

That investigator, assigned to the Manhattan federal prosecutors’ public corruption unit, was John Barry, who has since been tapped to be a deputy Suffolk County police commissioner in the department’s shake-up following the arrest of James Burke, the ex-Suffolk police chief who pleaded not guilty to federal corruption charges for allegedly beating a suspect and covering it up.

Barry testified at the Skelos trial that he stopped following the SUV when it unexpectedly pulled over on the side of the parkway. Walker, who was also on board, said AbTech didn’t come up on the ride to the NYPD officer’s funeral. Walker testified that Dean asked Mangano about the payments when they were walking outside the funeral home.

“He was asking if they were getting paid anytime soon,” Walker said. Walker testified that he replied: “Let me find out right now.” He called Kenneth Arnold, an assistant Nassau DPW commissioner. After the call, Walker told Skelos that AbTech “will be getting paid very soon.”

After the funeral, Dean told Adam in another wiretapped call: “All claims that are in will be taken care of.”

Walker testified that although stormwater was a concern, Sandy recovery was the top priority when Adam first contacted the deputy county exec. Walker said he prioritized AbTech to appease Dean.

“If he’s not happy with the actions of the county…it could potentially be a problem,” Walker said, adding that he wanted the then-Senate Majority Leader to be “in a good frame of mind about the county.”

In addition to evidence that Adam had contacted Walker about AbTech from the start, Walker testified that he knew Dean was also talking to Walker’s boss about the company’s contract.

“I knew it was important to the county executive because he had been contacted by the senator,” Walker testified, noting that “very rarely” does an elected official contact him about a contract.

Tellingly, Walker noted that complaints he fields about Nassau not paying its bills are “too common.” The county paid AbTech a total of $150,140.59 between June 9, 2014 and April 15, 2015. Nassau suspended the contract a week after the Skeloses were arrested in May 2015.

As Walker testified, Judge Wood repeatedly told the chief deputy county executive to speak slower so the transcriber could keep up. When he failed to listen, Wood told the prosecution to pause between questions to give the court reporter a chance to catch up. In the midst of Walker’s fast-talking testimony came one of the trial’s biggest revelations: Walker admitted that he is under federal investigation for awarding contracts to campaign contributors.

“I am ready to answer any questions that they may have,” Walker said of the investigation by prosecutors for the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of New York, which includes LI. Walker has not been charged with a crime. It is unclear whether the immunity that Manhattan prosecutors gave him in exchange for his testimony in the Skeloses trial would help him in that federal probe.

But the bombshells didn’t stop there. During a sidebar proceeding, Gage, Dean’s attorney, said that federal authorities declined to give immunity to Mangano, who had threatened to invoke his Fifth Amendment right against self incrimination if he was subpoenaed to take the stand, Newsday reported. Kevin Keating, the county exec’s Garden City-based attorney, reportedly told his client to plead the Fifth “if he is asked questions about unrelated matters,” were he to testify at the father and son’s corruption trial.

THREE AMIGOS

By Jan. 21, 2015, then-state Sen. Skelos was back to playing nice in public when he appeared at the governor’s annual State of the State address, which was held later than usual due to the death of his father, Gov. Mario Cuomo, on New Year’s Day.

The delay evidently gave the Skeloses more time to scheme.

“Who are you going to meet with next week?” Dean asked Adam in a wiretapped call that month. Adam, signaling he’d begun to worry about getting caught breaking the law, replied: “I’m hesitant to talk to you on the cell phone.”

Before the governor’s address, Dean and Sen. Martins were wiretapped strategizing on a statement to proclaim the budget priorities of the Long Island Nine, as the state Senate delegation from Nassau and Suffolk counties is known. They wanted to focus on funding for water quality projects. Dean was careful to include stormwater projects—a distinction absent from GOP talking points at the time, evidence later showed—as among his priorities, while the two discussed who would get credit for the funding and how to use it to their political advantage.

“That resonates with people, with voters,” Sen. Martins said, making sure the public knows the money is for clean water and the environment. Acknowledging the need for sewer infrastructure investments to spur construction, Dean added: “It’s something that’s good—that developers like, but the environmental nuts would like it, too.”

Once it was time for his State of the State, the governor made a show of his bipartisanship relationship with then-Majority Leader Skelos and then-Speaker Silver.

“It was a hard four years,” Cuomo said, relishing being re-elected to his second term. “It has taken a toll, some greater tolls on some of us than others. But look where we were when we started.

“Look at how good Dean Skelos looked just four years ago,” he continued. “And look at Shelly; four years ago he was looking good. We were like Saturday Night Fever dudes just four years ago. And four years later—it’s really sad, pictures don’t lie, it’s true, it really is true. But we believe, and I am sure I speak for Dean and Shelly, it was worth it and we would do it all over again, wouldn’t we?”

Later, he delivered the punch line: “We are going to be our own version of the three amigos.” The screen behind him flashed with the photo-shopped caricatures of the three politicians on horseback dressed as the faux Mexican cowboys in the ‘86 comedy ¡Three Amigoes! starring Chevy Chase, Steve Martin and Martin Short.

In the 10,323-word address, only 99—less than one percent—involved proposals intent on restoring the public trust in politics and politicians. The next day, federal investigators arrested Silver on charges of conspiracy to commit honest services fraud and extortion under color of official right—the same charges on which the Skeloses were later convicted. The ex-senator and son were also convicted of soliciting bribes in connection with a federal program.

Near the end of his news conference detailing the case against Silver, which rocked Albany, Bharara was asked if any other arrests were anticipated. The federal prosecutor famously told reporters: “Stay tuned.” The rumor mill immediately kicked into high gear.

STRAIGHT TALK

A week after Cuomo’s speech came the spiciest moment caught on the federal wiretap, but it had nothing to do with the Skeloses conspiracy—instead, prosecutors used it to show what Dean sounds like when he’s not talking in code.

In it, Dean, Sen. Martins and state Sen. Carl Marcellino (R-Syosset) bashed Mangano, a fellow Republican, while expressing their outrage over the Nassau exec’s proposal to install electronic billboards on the Long Island Expressway, according to the Jan. 28, 2015 wiretap.

“Mondello keeps talking about unity, unity and all this shit,” Marcellino told Skelos, referring to Nassau Republican Chairman Joe Mondello, as the two senators complained that Nassau leaders hadn’t give them a heads-up about the proposal before it was published on the county’s planning commission meeting agenda.

“We try to do whatever we can to help the county,” Skelos told Marcellino. “Most of it turns into shit because they don’t know what the fuck they’re doing there. And…we get the crap, and then they do this, and they don’t even tell you.”

Neither Nassau Republican senator held their tongue.

“It’s unbelievable with these guys,” Marcellino told Skelos. “They can’t seem to get out of their own way. They see numbers that’s going to give you millions of dollars, and then they jump, ‘Oh, let’s do it.’”

Marcellino said: “When I see Ed Mangano, he’s going to get an earful.” Later, he added: “This is going to be on a state road. You know we’ll get blamed.”

Skelos told Marcellino to call the state Department of Transportation and have the agency reviewing the permits for the billboards to “just kill the fucking thing.” The proposal died.

In another call with Sen. Martins recorded the same day, Skelos recalled the county executive’s aborted roll-out of school-zone speed cameras after Nassau officials had requested that the senators help to get state authorization for them.

“They’re incapable,” Martins replied.

Those Skelos calls had no “corrupt official speak,” as prosecutors called it, such as mention of “the situation” or “that guy.” But they were quite revealing just the same.

‘TOO MANY FUCKING FEDS’

Barely a week had passed after Silver’s arrest before WNBC New York first reported that then-Sen. Skelos was under investigation by the same prosecutors who had just arrested Silver. But the Republican leader refuted the story, which was based on anonymous sourcing.

“Last night’s thinly-sourced report by WNBC is irresponsible, and does not meet the standards of serious journalism,” Cummings, his spokeswoman, said in a statement. “Senator Skelos has not been contacted by anyone from the U.S. Attorney’s Office. As such, we won’t be commenting further.”

Later, testifying at her former boss’s trial, Cummings said that when she first spoke to Dean about AbTech, she mispronounced the company “A-B-Tech,” but the senator corrected her.

Regardless of how much the senator’s staff tried to poke holes in the story, the news made the Skeloses radioactive—and by extension, AbTech.

Nicholas Barella, a partner at Albany-based Capital Group, a lobbying group that an AbTech subsidiary hired to help get the design-build legislation passed, was understandably worried.

“We gotta rethink the whole thing out…too much is going down,” Barella told Adam on a wiretapped call two days after the story broke. “There’s too many reporters involved and too many fucking feds.”

Adam told Barella, a good friend of Dean’s, that Adam thought Cuomo had planted the story. But Barella was unswayed. That same day he sent an email to AbTech’s White terminating Capital Group’s lobbying agreement, evidence showed.

Although Adam was worried, he didn’t let the news stop him from going about his business. Days later, in another wiretapped call, Adam told White, who had become a friend outside of work, that Adam got his wife a puppy so that she would be more comfortable with Adam staying in hotels on nights when he worked late.

“The things I do to stay out and get a piece of ass,” Adam told White in the call played in court.

At 7:30 a.m. the following day, federal investigators knocked on the door of White’s Connecticut home with questions about Adam and AbTech. After consulting with his attorney, White agreed to record his calls with Adam and wear a wire during an in-person meeting with him. But it would take some time to set up.

“I really can’t talk to you; you should talk to Bjornulf,” Barella told Adam in another February 2015 wiretapped call. “We no longer work together. He’ll tell you why.”

Sounding confused, Adam asked: “Really?”

“Adam, do you read the newspapers?” Barella replied. “We have to protect me and you. Got it?”

Days later, when Adam learned that The New York Times was working on a story about his father’s investigation, it finally sunk in.

“I’m nervous now,” Adam told White in another wiretapped call.

Around this time, even deputy Nassau exec Walker, who was separately lobbying the governor’s office on the design-build bill for AbTech, stopped responding to Adam’s messages, according to court testimony.

INFORMER

Ironically, White had drinks with Adam at the W Hotel in Manhattan—where the two men had first met—but this time White was secretly recording the conversation at the FBI’s direction.

During their night out on Feb. 13, 2015, Adam told White how he tried to evade both the federal investigation and state lobbying disclosure laws.

“I don’t do lobbying, I do consulting,” Adam said, in snippets of the conversation played in court.

White had become a registered lobbyist so he could meet with lawmakers—starting with state Sen. Tom Croci (R-Sayville), the former Islip Town supervisor—and pitch them on the design-build bill himself. But Adam had another trick up his sleeve.

“After you meet with Tom Croci, that night I’m going to his fundraiser, and that’s all I’m going to talk to him about,” Adam said in the recording. Adam said that the benefit of this strategy was there would be no official record of him meeting with Croci, unlike the documented schedule of senators’ meetings during regular business hours.

Toward the end of the conversation, White asked Adam if there was a “safe number” he could use to call Adam. He gave White the number to his “burner phone”—a prepaid cell phone that allow users to avoid having a registered phone bill in their name. Adam thought his burner would be impossible for the FBI to tap. But all they needed was the number that White later provided.

The FBI told White to tell Adam that Croci was reluctant to back the design-build bill, which a public employees union and a trade group opposed, because Croci didn’t know where Dean stood on it. After White met with Croci, he relayed that message but Adam was undeterred.

“I’m going to see him tonight at the West Lake Inn and I will tell him where we are on it,” Adam said in a Feb. 23, 2015 wiretapped phone call played in court.

That same day, Adam also called state Sen. Michael Venditto (R-Massapequa)—son of Oyster Bay Town Supervisor John Venditto, a Republican—and asked the senator’s staff if they’ll be attending the SRCC’s fundraiser that night. In a separate call to White, Adam said that he would set up a meeting with White and Sen. Venditto since Croci wouldn’t back the bill, according to court testimony.

“Not that he’s less cautious, but he’s more supportive of things like this,” Adam told White, referring to Sen. Venditto. “Normally I’m never cautious, but with everything going on I’m trying to be.”

The next day, Adam learned that his father’s staff had cancelled White’s meeting with Sen. Venditto. Adam called Dean to confront him, but first, unaware that his cell phone was tapped but suspecting that the senator’s might be, told his dad to call him back on his wife’s phone before they discussed the issue.

“I don’t work with that person anymore,” Adam assured his father, referring to White. “He’s just a friend.”

Dean hinted that he was nervous, too.

“Right now we are in dangerous times, Adam,” the then-senator said in the recorded call. His son replied: “Believe me, I understand, which is why I have nothing to do with this.”

Days later on another recorded call, Adam told White to text Adam “my girlfriend’s bothering me” as code for Adam to call White back on the burner, according to court testimony.

In an attempt to avoid email evidence, Adam also told White later that month to mail Adam paper copies of White’s pitch to Croci so that Adam could hand deliver it to his father and Mangano. Adam called Mangano’s office to set up the meeting, but it was unclear if then-Sen. Seklos’ son ever delivered the paperwork.

By March, Adam was see-sawing between confidence that he was in the clear and being on the verge of a mental breakdown from the weight of his growing paranoia.

“Apparently it’s all… gone to rest,” Adam told White in a March 23, 2015 recorded call. “It’s lost steam I guess,” Adam said, estimating that the probe into his father was “95 percent closed.”

According to the wiretaps, he was also annoyed that negotiations over ethics reform proposals in the wake of Silver’s arrest were distracting state lawmakers from taking up the design-build bill.

Days later, while trying to call his father, Adam vented his frustration about how they couldn’t speak openly on the phone anymore. He suggested on the phone that he should “just send smoke signals or a little pigeon with [a] fucking note [tied] to its foot.” Once father and son finally did speak, Adam said he was “freaking out.”

“You can’t talk normally because it’s like fucking Preet Bharara is listening to every fucking phone call,” Adam said. “It’s just fucking frustrating.”

“It is,” Dean replied.

FALLOUT

Two weeks after then-Sen. Skelos was arrested—and despite his best efforts to keep his majority leadership post regardless—he stepped down and state. Sen. John Flanagan (R-Northport) replaced him.

After his arrest, Dean also took a “leave of absence” from the Uniondale-based law firm of Ruskin Moscou Faltischek, where he worked for 20 years and was listed as “of counsel.” But he refused to resign from his senate seat. In response to news of the Skeloses’ arrest, Nassau legislators had proposed local lobbyist disclosure bills. Democratic lawmakers maintained that the version the GOP-controlled county legislature ultimately passed didn’t go far enough. Nassau prosecutors—who later had investigators watching the federal trial, too—also opened an investigation into Nassau’s contracting process, which the county District Attorney Madeline Singas called a “recipe for corruption.”

Despite the revelations of the Silver and Skeloses cases, state lawmakers remained reluctant to reform what Bharara dubbed a “cauldron of corruption.”

State Sen. Tony Avella (D-Queens) was uniquely qualified to shed light on that reluctance, since he was chair of the state Senate ethics committee when Dean was arrested. Avella had landed the chairmanship because he is a member of the Independent Democratic Conference (IDC), which formed a power sharing agreement to keep GOP senators in control despite the Republicans’ losing their slim majority in the 2012 elections.

“I quickly found out, once I became chair of the ethics committee of the Senate,” Avella testified at Skelos’ trial, “that no bills had ever been referred to that committee and no bills had ever been voted out of that committee.”

Avella told jurors that in March 2015 he scheduled the committee’s first hearing in years, but he was told to postpone it and no new date was given. He later told reporters that shortly after the Skeloses’ arrest, he was reassigned to another committee. But, if he had known about Adam’s business ties, he said he would have voted differently on the real estate and medical malpractice legislation—and he would have aired the conflicts of interest.

“It would have indicated that undue influence was given to an issue of legislation based on personal interest,” Avella testified. “His family personally benefited from the passage of this bill, which is inappropriate.”

But even Avella, a self-described “hard critic” of the real estate industry’s heavy-handed political campaign spending, couldn’t wash his hands of its influence. During cross examination, the Skeloses’ defense attorneys pointed out a newspaper article in which Avella was criticized for accepting $40,000 from four separate Glenwood-owned LLCs, short for limited liability companies.

Glenwood and other campaign donors routinely donate to political candidates using LLCs—in this case, subsidiaries of larger companies—to get around the state’s spending cap on campaign donations. In state campaign finance law, it’s known as the LLC loophole.

Common Cause, a nonprofit good government advocacy group, found that Glenwood donated nearly $13 million to political campaigns between 2005 and 2014. The majority of the donations were made by the company and dozens of LLCs under its control. On the witness stand, Dorego defended the practice, saying that it’s simply how Glenwood gets a say in the political process.

“Right now it is legal and you have to raise money to run for office, unfortunately,” Avella told the court.

“The contributions have absolutely no impact on legislation,” Skeloses’ defense attorneys quoted Avella as telling the reporters who called him out on the hypocrisy of being against the LLC loophole yet taking campaign money through it. On the stand, he was more specific: “When it comes to me, yes.”

At this year’s State of the State, Cuomo, a big beneficiary of the LLC loophole himself, proposed closing it as well as stripping convicted lawmakers of their pensions, limiting legislators’ outside income and other like-minded perennially proposed reforms in Albany that often amount to the usual: All talk and no follow through. The only measure the legislature has approved this year sets eight-year term limits for leadership posts in the state Legislature—codifying a rule that has been in place in the state Senate since 2009.

Of course, New Yorkers shouldn’t expect the state Senate ethics committee to hold any hearings on proposed reforms—same goes for the Assembly ethics committee, which reportedly only meets to discuss internal complaints against lawmakers. When state Sen. Michael Gianaris (D-Queens), a member of the ethics committee as well as the senate minority leader, wrote a letter this month to the committee’s latest chairman, Sen. Croci, to “finally take concrete action and hold hearings to address the numerous reform proposals that the public is demanding,” the Islip Republican wrote back to say that would be “beyond the legal scope” of the committee. Croci is also sponsoring legislation to bar convicted lawmakers from recieving pensions.

As for the Skeloses, a special election is scheduled for April 19 to fill the disgraced senator’s seat while they appeal their convictions. They’re hoping for an acquittal, although ex-Sen. Skelos’ predecessor, former state Senate Majority Leader Joe Bruno (R-Brunswick), who led the chamber for 13 years, waited five years for his federal corruption conviction to be overturned on appeal before being found not guilty following a retrial in 2014.

Ex-Sen. Skelos is not alone in hoping for such an outcome. Ex-state Senate Majority Leader Pedro Espada (D-Bronx), who led the chamber from July 2009 to December 2010, was convicted of embezzlement in 2013. He is serving five years in prison and lost his most recent appeal. Ex-Senate Majority Leader Malcolm Smith (D-Queens), who led the chamber for six months in 2009, was convicted of bribery in February 2015. He is serving seven years in prison while appealing his conviction. Ex-state Senate Minority Leader John Sampson (D-Queens), who led the chamber’s Democratic caucus from 2011 to 2013, was convicted of obstruction of justice last summer. He has also vowed to appeal and faces more than a decade in prison when he’s sentenced.

And those leaders only make up a fraction of about two dozen state elected officials who’ve been arrested over the past decade. All were expelled from office upon their convictions. Then, as now, the question remains: Who’s next?

Stay tuned.