About 1.3 billion years ago, two black holes about 29 and 36 times the mass of the sun, respectively, collided at nearly half the speed of light, forming a new, massive, super-spinning black hole, which, within the final milliseconds of its birth, emitted an eruption of energy equivalent to about 50 times that of the entire universe.

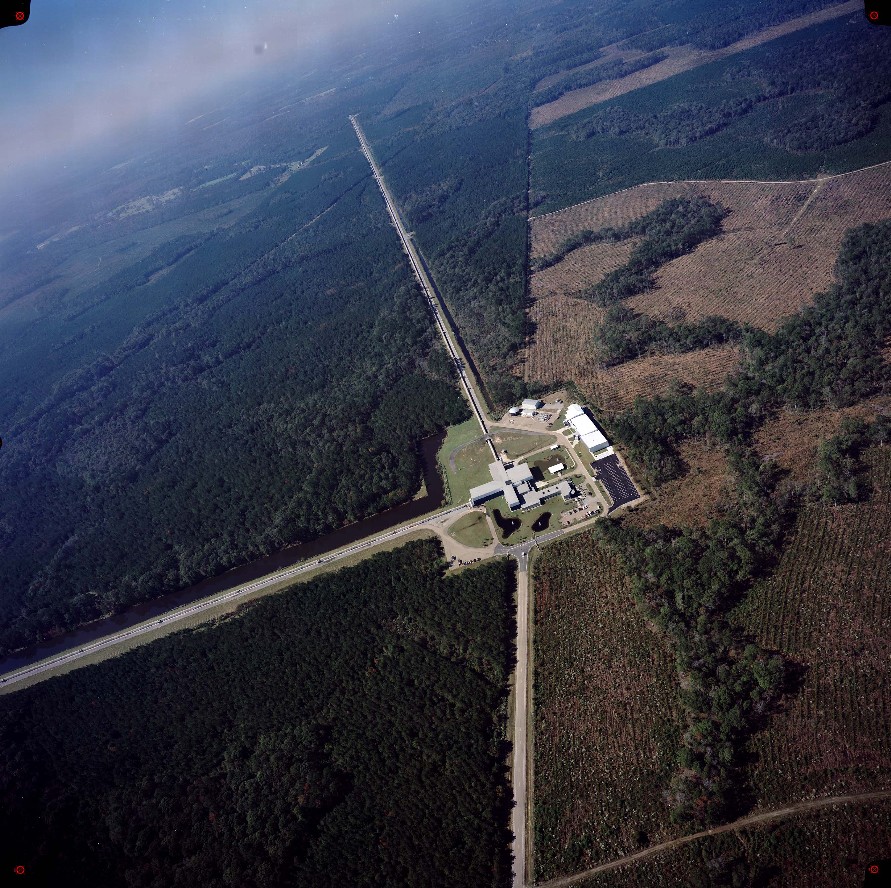

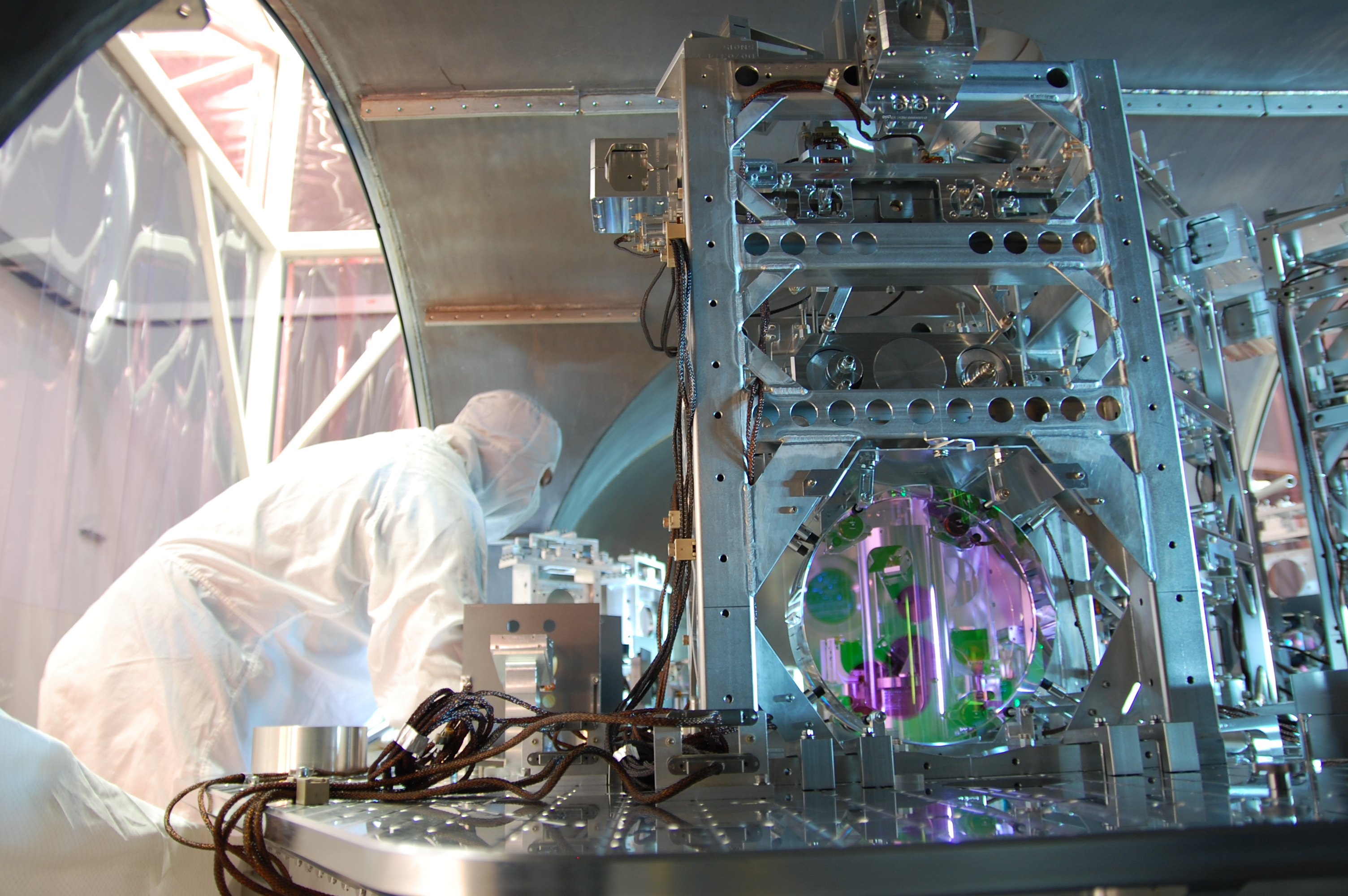

This nearly incomprehensible explosion of energy—a cosmic cataclysm creating literal ripples in the very fabric of spacetime, dubbed “Gravitational Waves”—was detected Sept. 14, 2015 by the twin Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) detectors in Livingston, Louisiana and Hanford, Washington.

The existence of these mind-bending, realm-shattering waves was confirmed Thursday morning at the National Press Club in Washington, DC by the National Science Foundation (NSF), which funds the LIGOs. The announcement validates a major component of Albert Einstein’s 1915 general theory of relativity—E=mc2—and, in the words of the NSF, “opens an unprecedented new window to the cosmos.”

The collision of two black holes had always been predicted, but never observed. LIGOs’ detections are being hailed as indisputable evidence.

“This detection is the beginning of a new era: The field of gravitational wave astronomy is now a reality,” explains Gabriela González, spokesperson for the LIGO Scientific Collaboration (LSC)—a consortium of more than 1,000 scientists from around the globe—and professor of physics and astronomy at Louisiana State University.

Einstein predicted gravitational waves in 1916. His theory of general relativity is essentially the foundation for our understanding of gravitation, and was published the previous year. In a nutshell, it describes gravity as a property of space and time, aka spacetime.

Spacetime, in its original, most stripped-down terms, regards the concept of “space” in this universe as comprising three dimensions, with “time” occupying an additional, singular dimension. Other theories predict many, many more dimensions than these four.

To Einstein, gravity was a property of spacetime’s curvature. Mass dictates the degree of the latter. Boiled down, Einstein theorized that time and space could not exist as separate, disparate entities unto themselves. Instead, they are interwoven, mandating that events taking place at the same moment for one can also transpire at different moments for another.

Sonic Boom, Earthquake, Government Cover-Up, Meteor, Or Something More Sinister?

It is impossible to talk about Einstein’s general theory of relativity, however, without at the very minimum, mentioning the divine revelations proposed in his lesser-known, though arguably even more significant, special theory of relativity—a precursor to his most famous understandings, first proposed a full decade prior, in 1905. Published within his “Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper,” translated, “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies” paper, it resolves variances within the fundamental theories of electrodynamics, and, proposes new understandings of the mechanics pertaining to the speed of light.

In short, Einstein (with at least some credit to a handful of others, namely Hendrik Lorentz, Sir Isaac Newton, Heinrich Hertz, James Maxwell and Christian Doppler) proposed that essentially, the speed of light is absolute, thus, setting a benchmark, if you will, for the quantification of all energy, information, and matter—an existential parameter, of sorts! With this in mind, consequentially, our comprehension of “time” moves slower as our speed relative to other objects approaches the speed of light.

Taken as a whole, these two theories of Einstein’s lay the groundwork for real, successful time travel, albeit only in one direction, forward, into the future. Theoretically speaking, approaching the speed of light on an excursion within a set period of reference would enable the time traveler to achieve that precise moment in much shorter “time” progression than those not accelerating at such speeds, and thus, biologically age slower. The progression of “time” would also appear to pass much slower for those within a gravitational field, Einstein’s theories predict.

Basically, the faster an object travels, the more spacetime warps.

Distortions in our experience of spacetime, perhaps best envisioned through the symbiotic relationship to our understanding—and now validation of—these gravitational waves, or “ripples,” may bring mankind as an entity-species yet one step closer to harnessing the reality of such a phenomenon, again, foretold more than a century ago.

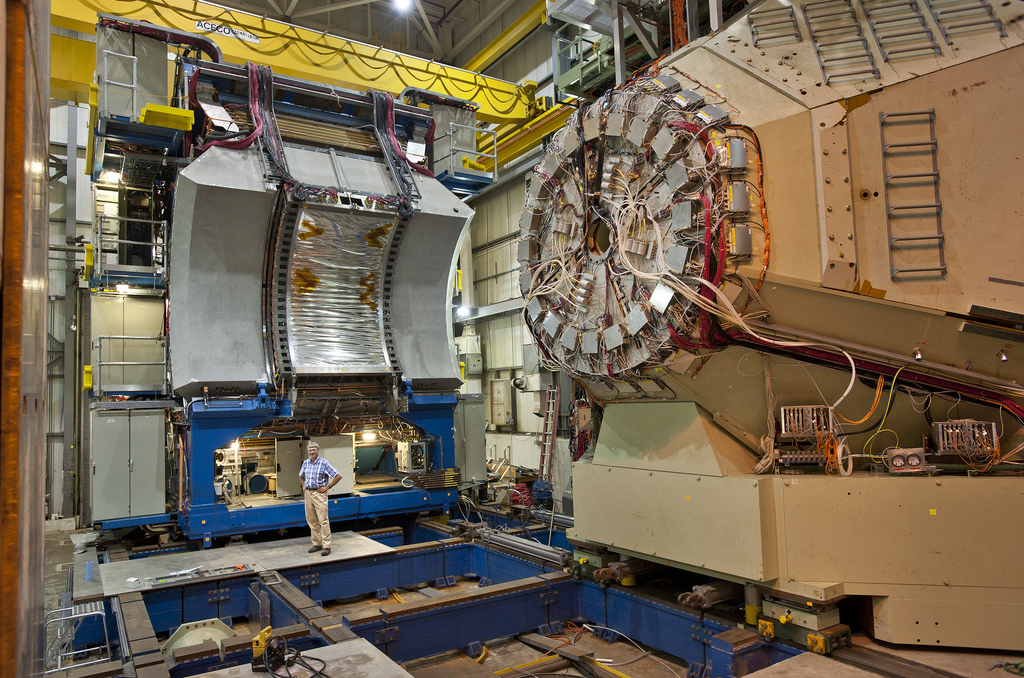

We can discuss so-called “Dark Matter,” wormholes, and the potential for humans to open, and pass through, interdimensional spacetime gashes (think Walter Bishop’s destructive-yet-salvationary doorways in Fringe) in another post, as well as more about the subterranean electromagnetic corrider-colliding Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider currently conducting related experiments at Brookhaven National Laboratory (which “relies very essentially on Einstein’s theory of relativity,” Berndt Mueller, BNL’s associate director for nuclear and particle physics, told the Press some “time” ago); the Large Hadron Collider near Geneva; and reverse-engineering of downed “extraterrestrial” spacecraft to enable our present-dimensional bodies to withstand such cosmic associations at another moment in “spacetime,” dear readers.

Oh Einstein. Perhaps the next hundred “years” of research into your theories will yield even more validations of the unknown, enable us to also “travel” backwards (you know what I mean), and thank you in person ourselves for your divine, transcendental musings.

Stay tuned.