In the late 1930s, thousands of German Americans spent their summers at Yaphank’s Camp Siegfried. They were greeted by a Nazi-saluting welcoming party as their train—the “Siegfried Special”—screeched to a halt. The journey wasn’t complete until they made a two-mile march to their lakeside enclave festooned with swastikas and teeming with unabashed pride for the Fatherland and its sinister, mass-murdering leader.

They’d walk passed streets named after Nazi luminaries: Adolf Hitler, Joseph Goebbels, and Hermann Goring, to name a few. Many people came after receiving postcards from the German-American Bund, a pro-Nazi organization in the United States, promising a bucolic summer haven.

“For at the camp you will meet people that think as you do…cheerful people, honest and sincere, law abiding!” declared one postcard advertising the camp.

Once they made their way into the encampment, some adults donned Nazi military regalia while their children were subjected to Nazi propaganda.

As was customary, kids dressed in Hitler Youth garb were instructed to sing Nazi songs.

“When Jewish blood drips from the knife,” they spewed, “then will the German people prosper.”

The pro-Nazi camp endured for four years, right until World War II broke out.

“They wanted to propagandize as much as possible German-American youth,” says Steven Klipstein, assistant director of the Suffolk Center on The Holocaust, Diversity and Human Understanding.

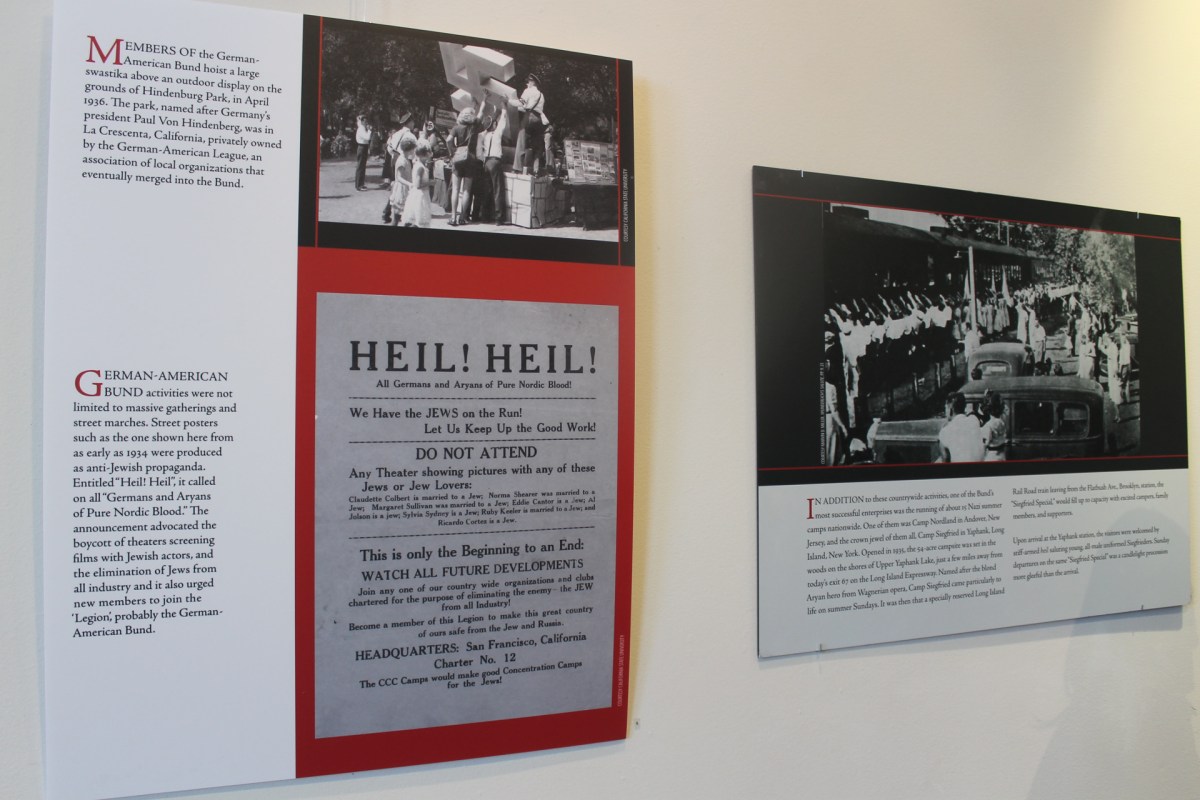

With the exhibit called “Goose Stepping on Long Island: Camp Siegfried,” the nonprofit group, based within Suffolk County Community College (SCCC), is bringing one of the most mysterious and perplexing periods of Long Island’s history back to the forefront on SCCC’s Riverhead campus. It is on loan from Queensborough Community College.

Running through March 31 on the campus’ Montaukett Learning Resource Center, the exhibit can be disorienting at first.

When Jill Santiago, the group’s Holocaust Educator, tells her students about what happened on LI eight decades ago, they are often astonished, she says.

“This is not an easy population to shock, so if you can shock them, you can see there interest immediately spikes,” explains Santiago, who is also a history professor at SCCC.

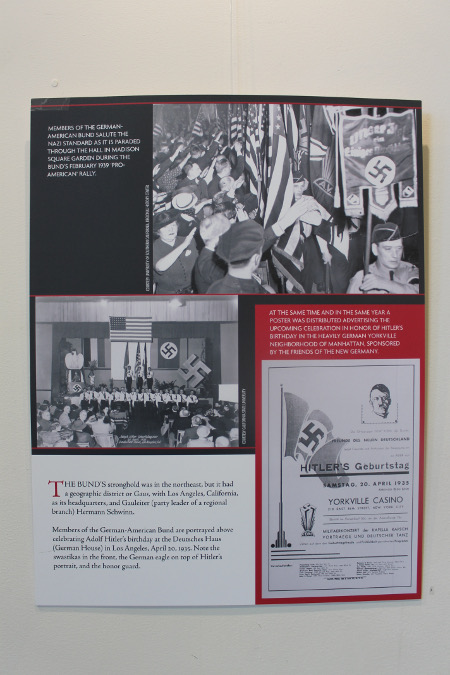

On Wednesday, about three dozen people perused the exhibit’s powerful, disturbing photos while Klipstein provided an account of what life was like on suburban Long Island before World War II. Enjoying refreshments, visitors got a chance to check out photographs from a German-American Bund rally in 1939 at Madison Square Garden, which attracted thousands of people, as well as a large number of opponents who gathered outside the arena.

The photos also document people gathered around a stage featuring a podium flanked by the American and Nazi flag, Hitler-sympathizers greeting new arrivals at the Yaphank train station, children wearing matching uniforms, and camp-goers waving Nazi flags as dozens of onlookers performed the “Heil” salute.

Not all of the displays are as provocative; a number simply show kids frolicking in the lake and adults mingling on the lawn.

“The camp is really being advertised as a place for German Americans to get together with like-minded people…but there was definitely an anti-Semitic tone to it, and very anti-communist, eulogizing Hitler,” Santiago says.

The plot of land in which the camp existed was owned by the German-American Bund, but was eventually transferred to the German American Settlement League in 1937. The camp itself, which came under intense government scrutiny, was abandoned in 1939, after Frtiz Kuhn, national leader of the German-American Bund, was arrested for embezzlement and Germany invaded Poland.

A lawsuit filed last October by a Yaphank couple unable to sell their house in the area rekindled interest in the camp. Philip Kneer and Patricia Flynn-Kneer, who both have German roots, were trying for six years to sell their home but couldn’t because of the league’s “racially restrictive policies” that only permitted purchasers to be of “German extraction,” according to the federal complaint. Both parties reached a settlement in January stipulating that the league will welcome new homeowners irrespective of their race or ethnicity. It also agreed to refrain from using any Nazi-related symbols on the property.

The original property was purchased by the Bund in 1935, and at its height welcomed approximately 100,000 people to the camp. Many of the people lived in the tri-state area and either enrolled their children in the camp for most of the summer or came for celebratory occasions, like “German Day.”

“They wanted to transform America into a Nazi system,” Klipstein told the audience.

Kuhn, a frequent visitor, had dreams of being the American Fuehrer if the Nazi’s won the war, and gave a speech at the camp one summer about the importance of properly educating children about the group’s “ideals.”

“The youth of our great Bund are the hope, the life line of our organization. Through them we must live into the future,” he said, according to testimony he gave a Congressional committee investigating “Un-American propaganda activities” in the United States. “It is, therefore, necessary that we must stand united behind them, educate them, and raise them to manhood and womanhood with our ideals imbedded in their hearts. We must fight together for their freedom.”

“We [must] work to win over the youth of all German-Americans and some day when our labor has reaped its reward we shall hear fine and strong German-American youths come marching from the east and west, from the south and [north]—marching onward to build a greater nation,” he said, according to testimony.

German-American children received more than a lesson in “ideals” at the camp.

Every Sunday morning, according to the committee’s report, boys and girls would join separate ranks to greet “storm troopers” arriving to the camp.

“Some of the scouts march behind the German swastika and the American flag to the railroad station 2 miles away through Yaphank,” according to the report. “They line up at attention beside the track and, as the train pulls in, their arms are outstretched in a Hitler salute to the arriving guests.”

There’s little evidence available to definitively say how many people joined the Bund, which Kuhn maintained was nothing more than a political organization with divisions in the east, midwest and western part of the country. But the government believes the Bund had as many as 25,000 loyal followers.

In its report, the committee said that testimony from several witnesses “establishes conclusively that the German-American Bund received its inspiration, program, and direction from the Nazi Government of Germany through the various propaganda organizations which have been set up by that Government and which function under the control and supervision of the Nazi Ministry of Propaganda and Enlightenment.”

The rally at Madison Square Garden in 1939 turned out to be the Bund’s last hurrah. That same year, Kuhn, its leader, was arrested by the feds. It’s also important to note that, although the camp was a bastion for Nazi sympathizers, it did have its detractors. Namely, those in the surrounding communities saw them as a “menace,” according to Klipstein, and camp efforts to expand into Riverhead were thwarted by Riverhead Town.

All these years later, Klipstein says it’s important to shine on a light on what he calls Long Island’s “checkered past.”

“As much as we repeat the message [of intolerance] these things still happen,” he told the audience.

The Suffolk Center on the Holocaust, Diversity & Human Understanding continues to teach the lessons of the Holocaust, but also tackles hate crimes, slavery, and modern-day human trafficking.

“This exhibit is really about examining a period of history that’s not very well known and kind of promoting the idea that we have to take a stand against things that are rooted in prejudice of hate,” Santiago says.

“Goose Stepping on Long Island: Camp Siegfried” runs through March 31. It is located at Suffolk County Community College’s Montaukett Learning Resource Center in Riverhead. The exhibit is free. Special tours can be arranged by calling 631-451-4700. The exhibit is on loan from the Harriet and Kenneth Kupferberg Holocaust Center and Archives at Queensborough Community College.