The time has come for Long Islanders to get all aboard the Long Island Rail Road’s third track proposal.

As resurrected by Gov. Andrew Cuomo in his state of the state address in January, the third track would run along a 9.8-mile stretch between Floral Park and Hicksville that serves 107,000 riders on an average weekday. During peak times, the LIRR is forced to run trains in only one direction, which becomes a huge bottleneck whenever equipment breaks down or some other unforeseen delay arises. This main line expansion is intended to relieve that decades-old bottleneck. But almost as soon as the governor announced it, community opposition—especially within Floral Park—was galvanized.

Given the project’s troubled history, the protesters had good reason to raise their voices, especially since many who owned homes along the main line feared that their properties would be condemned by the “big bad” New York State.

Recently, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority released what’s known as scoping documents that say what will be included in the draft environmental impact statement, an important step in getting the once-estimated $1.5-billion project underway. While the final cost is still being calculated, the main aspects are clear. Essentially, the MTA is planning to plan.

In its most recent iteration, the third track may not have as much impact on nearby residential properties as once was feared. Even better, the current project is expected to remain within the existing LIRR right-of-way and eliminate each of the seven grade crossings in the project’s corridor. This benefit alone is a sizable carrot to the municipalities protesting any expansion of the railroad. The MTA is also looking to require the acquisition of fewer than 10 commercial properties.

As such, Long Island’s support for the third track should be a no-brainer—but only if the proper upgrades are made to the system in conjunction with the line expansion. These upgrades are needed to not only enhance the effectiveness of the third track project, but allow for the region to net the maximum benefits of other large-scale initiatives being undertaken by the LIRR such as East Side Access—now slated to be completed in 2023 (only 14 years later than first predicted and at $10.8 billion only $6.5 billion more than initially projected)—and the double track planned between Ronkonkoma and Farmingdale to relieve congestion in that heavily traveled line.

Long Island’s future depends on its LIRR connection.

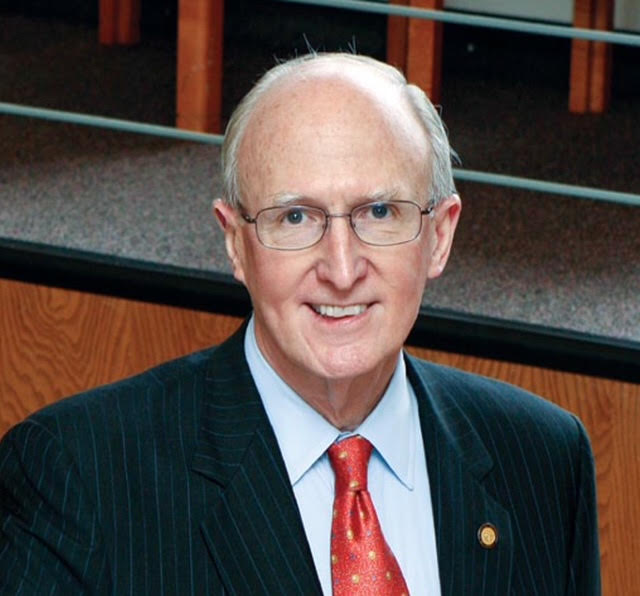

“We talk about rebuilding our downtowns, locating affordable housing near train stations, and getting people out of cars and into trains,” said Long Island’s veteran planner, Lee Koppelman. “The simple truth is that in order to do all that, you need to improve the service. That’s where multiple tracking comes in.”

Koppelman served 28 years as the first Suffolk County Planner, 41 years as the regional planner for Nassau and Suffolk, and now going on a decade as the executive director of the Center for Regional Policy Studies at Stony Brook University. Like so many of the other projects kicking around these days, Koppelman noted that the third track has been on the table for nearly 40 years.

Koppelman would like to take the third track concept even further, calling for the electrification of the LIRR’s main line from Ronkonkoma east out to Calverton, as well as adding multiple tracking on the North Shore branches.

The railroad is pushing hard for the third track because the East Side Access would bring the LIRR right under the East River and into Grand Central Terminal. That project’s completion would be truly transformative for the entire LIRR system. With East Side Access being the principal force behind a projected ridership increase of 27.5 percent within the next 30 years, the railroad is preparing the rest of the system for the residual demands. Adding the third track would have a huge impact.

During the peak morning commute, there is no eastbound service for one and a half hours, while peak evening does not have westbound service for an hour. While the data for reverse commuting is ambiguous, the complete lack of reverse service on that line during peak times is troubling indeed.

Also concerning are the seven locations in Nassau where the road meets the railroad. On a typical weekday more than 220 trains run along that track, and these crossing gates have to do their duty for each one that goes by. One industry insider told me that in New Hyde Park, they’re down 24 minutes out of every hour during peak times—and that’s an average, not when you’re stuck in a line of cars waiting for the gate to rise. The proposed overpasses should alleviate these commuting headaches and a compact redesign should reduce the project’s impact on the corridor.

When the third track was last discussed seriously, beginning in 2005, the projected cost was $1.5 billion. By 2008, the project was essentially dead-on-arrival thanks to the large number of properties slated for condemnation, and not enough political will to see it through.

The current iteration doesn’t have a final price tag yet, but Cuomo has made it clear that this project is a New York State priority. Fewer property purchases are required this time around, but more grade crossings are slated for elimination, so the cost will change. So far, $6.95 million was spent on related environmental studies. The third track’s completion is slated for some time in 2020. With the third track’s community outreach efforts modeled after those used by state officials during the new Tappan Zee bridge construction by hosting a series of community meetings, setting up a physical project center at the Mineola Train Station, and a sleek website, it seems the MTA and LIRR have learned the lessons of 2008.

According to the scoping documents, the MTA estimates that construction should take “three to four years,” but Long Islanders know how these things often work out.

In 2008, Carolyn Nardiello of The New York Times reported on the shifting justification behind the third track, as described by then-LIRR President Helena Williams. “The initial reason given for a third track was an increase in reverse commuting from Manhattan to Long Island. Mrs. Williams said that the railroad’s previous leadership thought that after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, businesses would relocate to Long Island and increase ridership. But that did not happen, and the railroad’s rationale for a third track changed—to that of relieving congestion on train lines.”

Meanwhile, ridership continues to surge, during peak and off-peak commuting times. The claim that reverse commuting has risen is problematic. Since the best policy is data-driven, the LIRR should release the details rather than sharing anecdotal evidence. The projected job and economic impact figures released by the Long Island Index and other third-track project supporters such as the Long Island Association are attractive (if not at times a bit pie-in-the-sky), but weary residents will be most receptive to hearing how the third track will improve their daily commute and their quality of life.

One cannot say the LIRR and MTA aren’t trying to win over their hearts and minds along the corridor this time around. Since the project was announced in January, officials met with village mayors, prospective commercial property owners who may be impacted, and area school boards. Local residents will get their turn to comment about the scoping of the DEIS in an upcoming series of meetings held in afternoons and evenings.

Moving forward, it’s critical that both the MTA and LIRR communicate the tangible benefits of the third track to the daily riders who know its present shortcomings better than anyone. They should also clearly spell out how getting rid of those seven crossing grades will positively affect the community as well as the commuters.

With good planning, the goal is a project that is regional in scope yet still local in implementation. The third track seems to hit both those notes. Let’s fast-track this project before it’s too late.

Rich Murdocco writes about Long Island’s land use and real estate development issues. He received his Master’s in Public Policy at Stony Brook University, where he studied regional planning under Dr. Lee Koppelman, Long Island’s veteran master planner. Murdocco is a regular contributor to the Long Island Press. More of his views can be found on TheFoggiestIdea.org or follow him on Twitter @TheFoggiestIdea.