Early this month, Betty Rosa, New York State’s new education chancellor, was on Long Island to visit Medford Elementary School, where she met with students, teachers and staff. Children in the dual language kindergarten program easily conversed with her in both English and Spanish.

As the highest ranking member of the state’s Board of Regents and the state’s education czar, the teachers and the superintendent regarded Rosa with respect. After all, she is the boss, with a capital B. But the kids took to her with the natural curiosity and comfort of childhood that essentially said, “She’s one of us.” She spoke their language. Literally.

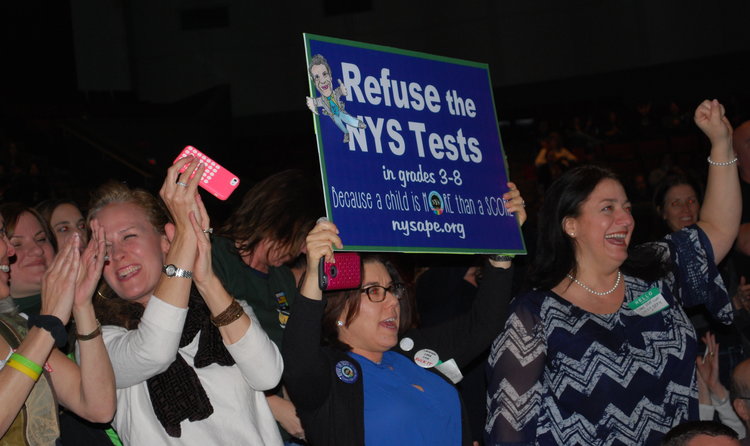

The friendly scene was in stark contrast to the heated battle pitting the governor, the teachers unions and grassroots public school advocacy groups against one another. The struggle came to a head during this spring’s testing season, culminating in a giant win for Long Island Opt-Out, a parent-led group that organized an historic number of test-refusals this year with almost 100,000 students—more than half of the student population in Nassau and Suffolk counties—opting out of state tests. Their message has been effective: No more Common Core. Despite incremental fixes promised by Gov. Andrew Cuomo and his so-called “Common Core Task Force,” they are still demanding concrete changes.

Yet, it remains to be seen how this evolving protest movement will improve or replace the current education agenda.

According to local public education advocates, the answer is multi-tiered. It includes elections: first at the state level and then at the local school board in an effort to tackle education policy from all sides. The goal is a shift away from schools’ increasing test-prep focus almost exclusively on math and reading skills—eschewing the arts and play-based learning—to a comprehensive curriculum that addresses what some advocates call the “whole child.”

“I think we need to emphasize the issue of high-stakes testing,” Rosa told the Press at a lunch in the school’s conference room with staff and other attendees. “I think we have to get back to what really matters, which is teaching and learning—deep learning—and our kids’ excitement to really become those deep learners. We have to change the narrative back to focus on teaching and learning, and less on one Kodak moment to capture all of that work. Believe me, parents know that those children are assessed constantly. The issue is having multiple ways to measure achievement.”

Rosa had spoken out against high-stakes testing at a press conference in March after the Board of Regents had selected her to the leadership post. She said that if she were not a board member herself and her children were elementary-school aged, she would opt them out of taking New York’s Common Core tests. On May 3, at the elementary school in Patchogue, she told the Press that she doesn’t believe the state should have the right to withhold funds from school districts with significant numbers of students who had refused to take state tests in April.

“Parents legally have a choice,” she said. “Given that choice, you cannot then legally punish school districts and schools for decisions that parents have made. So my goal is to make sure that we get to a better place where we don’t even have to have these discussions because it gets back to teaching and learning.”

But no sweeping changes can be made to a school’s education policy without the support of the local district’s board of education. Perhaps no one understands this better than Jeanette Deutermann, founder of Long Island Opt-Out Info, the popular Facebook page with more than 24,000 members that transformed into a robust-and powerful advocacy group. Deutermann told the Press that the election of nearly 100 Opt-Out members to local school boards, coupled with a new Regents chancellor, means that the tide is turning.

“The bottom line is that some of these big wins could mean huge, sweeping changes for some districts,” she told the Press. “Education is shifting in New York. It’s up to parents to elect the right board of education that’s moving with this philosophical shift of how we want to educate our children. It all goes back to something that Dr. Joe Rella [superintendent of Comsewogue schools] said: ‘You get the Board of Ed you deserve.’

“Parents are taking that seriously,” Deutermann continued. “This shift in philosophy is happening fast. We can’t wait 10 years if we want our children to experience this change.”

A key part of Long Island Opt Out’s strategy for the last two years has been to promote local supporters to their individual district’s school boards. So far, Long Island Opt Out has helped elect 94 candidates; 34 out of 57 this year, including local advocates Anthony Griffin and Sara Wottawa, who were elected on May 17 to their respective school boards.

“We have to change the narrative back to focus on teaching and learning, and less on one Kodak moment to capture all of that work.”

Griffin, an English teacher in Central Islip and co-founder of Lace to the Top, an advocacy group that promoted bright green laces to signify that “children are more than test scores,” was an LIOO-backed candidate who won a seat on the South Country school board. He’s hoping to influence his children’s public education experience from the local level.

“Changes in public education happen because of people,” Griffin told the Press in an email. “Some people want change to increase profits. Some want change to impose a belief. I want change to help students. As a board member in a student-centered district, I have an amazing opportunity to manifest those changes.”

Griffin is “thrilled to have the opportunity to bring what I have learned to my district’s board. Local control doesn’t exist without locally involved people.”

Wottawa is an outspoken parent in the Sachem School District. She joins two other LI Opt Out-endorsed board of education members who were elected last year to serve on the nine-member board.

“I’m hoping the three of us can work together to enforce change in the district,” Wottawa told the Press. “I would like to see Sachem take a more holistic approach in educating our children. I would like to see us move towards educating the whole child in Sachem. Most importantly, I would like to propel a unity in the Sachem community. Without the support of the majority of the community, positive change is nearly impossible.”

Though she’s in the minority on the school board, Wottawa is upbeat.

“Once we have more vocal public education supporters on our local school boards across the state,” she said, “I think we will see more positive changes.”

The special April 19 election of Assemb. Todd Kaminsky (D-Long Beach) to the State Senate to replace disgraced former GOP Senate majority leader Dean Skelos is seen as a key step in a populist-driven shift in the state’s education agenda, according to Diane Ravitch, a research professor of education at New York University and a former assistant Secretary of Education in Washington, D.C. under President George H.W. Bush. During the Clinton administration she was appointed to the National Assessment Governing Board, which oversees the federal testing program.

“Kaminsky’s victory is a victory for the leaders of the Long Island opt-out movement, who strongly supported his candidacy and the legislation he proposed as a member of the Assembly,” wrote Ravitch on her popular blog. “Kaminsky wants to decouple test scores from teacher evaluation, which would reduce the absurd pressure to raise test scores and the time lost by the arts and other subjects. Parents want their children to have a well-rounded education, not a test-prep curriculum.”

Kaminsky drew wide support from New York public school advocates after he sponsored three bills in the Assembly in February that would repeal several components of Cuomo’s Education Transformation Act. The bill would decouple teacher evaluations from test results, create an alternative pathway for graduation for students who do not wish to take or are unable to pass Regents examinations and repeal a provision that allows the state to place struggling or failing schools into receivership. Kaminsky’s recent election—although he’ll have to run again in November—allowed him to introduce his Assembly bills in the State Senate, where they have been referred to the education committee, which has until the middle of June, when the current legislative session ends, to determine their fate.

Kaminsky’s win at the polls came after public education advocates were buoyed by the Board of Regents’ 15-0 election of Rosa as Chancellor to replace Meryl Tisch, who was seen as a proponent of the high stakes testing.

Putting the emphasis back on teaching and learning may seem like a broad idea for education reform, yet Rosa cites her long history that includes her role as superintendent of a New York City community school as a key to her goals moving forward. It is that particular background that motivates her to embrace the vision of Michael Hynes, superintendent of Patchogue-Medford schools.

In direct opposition to Common Core, Hynes, has spearheaded a five-year “Whole Child” program, which he said can “save education” and be the “answer to Albany.” He presented it to the board of education on May 16.

Rosa said she agrees with the approach.

“I think it’s fabulous,” she told the Press. “Looking at the whole child, you’re looking at all of the needs of the child. I just compliment him and support him.”

She also supported Cuomo’s recent emphasis on community schools.

“I think many community schools have served as models that show that services are needed, that certain children come to school with certain needs and particularly children who come from disadvantaged homes where they cannot afford so many services,” Rosa said, adding that Hynes understands what’s needed. “I think that he realizes that we have to serve the whole child, not just the academic part. I think that’s extremely important. You have to have healthy children—children who enjoy being in school in terms of attendance. It’s just important for kids to have exposure to the arts and have other ways to develop their talents.”

The genesis of Hynes’ plan came from his opinion that the U.S. Department of Education and the New York State Department of Education have “for far too long been about two things: 1. test scores. 2. higher test scores,” he told the Press in an email. “Public education has been forced to move away from educating the ‘whole child’ due to the Regents Reform Agenda, NCLB [No Child Left Behind], and this crazy notion that our 15 year olds must score higher than other 15 year olds around the world or America is doomed. The funny thing is nobody talks about the test the 15 year old takes…yet many place great importance on the results.”

Hynes’ focus on the whole child comes as a result of his background in psychology and as a former elementary teacher in Bellport. He bases it on the simple concept that kids can have fun and learn in school simultaneously.

“They can play and utilize highly developed divergent thinking skills at the same time,” Hynes said. “We need to teach our children how to socially and emotionally excel. On the flip side, we also need to teach them how to recalibrate when they are having difficulty with something.

“This is where more play in schools comes into play (no pun intended), more recess, yoga, mindfulness, meditation, etc…” he continued. “I believe by focusing on social, emotional and academics for our children…we will be able to harvest the talents they never knew existed.”

This idea is in stark opposition to the EngageNY curriculum that the State Department of Education has been pushing to coincide with the Common Core standards. New York’s curriculum is taught from firmly established modules that give teachers little room to waver from. Because the high-stakes tests are based upon this strict curriculum—and because teacher evaluation had been directly tied to the test results—the idea of learning through play had been replaced with a high-pressure classroom atmosphere that Hynes said benefits neither the educator nor the student.

On a cold rainy Tuesday in early May, kindergarten children at Medford Elementary joyfully showed off their Spanish skills in a counting song to Rosa’s obvious delight. The dual language program facilitates fluency in Spanish at a young age.

“My goal is make sure our children have the resources and the opportunities to have access to quality education,” she said. “By that, I mean we need the resources, which means the money, obviously. Opportunities, like in this dual language program, these kids get an opportunity to learn two languages. And access is making sure that children who sometimes don’t have the finances get to places where those opportunities are.”

Rosa surveyed the room filled with enthusiastic five- and six-year-olds and said, “We have to fight for these children within the public schools.”