Right now the coolest, hippest exhibit space on Long Island has to be the “Cosmic Cavern” created by the internationally known street artist Kenny Scharf and currently installed at the Nassau County Museum of Art.

This psychedelic phantasmagoria of found objects ranging from a mirrored disco ball to a 45-turntable to hollowed out TV sets, electric guitars, dinosaur toys, plastic robots and so much more—all spray-painted luxuriantly with Day-Glo fluorescent colors and lit by black lights—has to be experienced at least once to be believed. It’s like stepping into a “Wild Style” abstract painting and entering a secret clubhouse that would leave your mom so speechless that she would forget to tell you to “clean up all this junk” before your father gets home from work.

My only regret is that its days are numbered. This unique Kenny Scharf show—and the fascinating Glamorous Graffiti exhibition on the second floor—will vanish from this historic Gold Coast mansion for good after July 10. Museum director, Karl E. Willers, who curated the show, should be commended for encouraging what once was—and to some critics still is—an outlaw form of artistic expression to take up residence within the former Frick Estate.

It almost defies imagination to consider where Scharf’s “street art” was displayed decades ago when he was part of the most famous (or infamous) trio of contemporary urban artists the East Village produced in the 1980s that included him, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. Each man’s style was distinctive. Haring drew the definitive white-lined figures boldly on a black background. Basquiat, who never studied art formally, was more expressionistic with dripping paint strokes and multiple layers of sometimes violent images, while Scharf took a more pop-surrealistic jokester approach by appropriating cartoon figures like the Flintstones and the Jetsons. Basquiat, who was taken under Warhol’s wing, died of a drug overdose in 1988. He was only 28. Last month, Yusaku Maezawa, a Japanese online retailer, bought one of Basquiat’s 1982 works for $57.3 million. And to think that Basquiat, born in New York, used to be one rent check away from being evicted.

Scharf grew up in Hollywood, California, and moved to New York City to study at the School of Visual Arts, where he met Haring, who was from Kutztown, Penn. In 1990 Haring died of AIDS with Scharf by his side. He was only 31. But Haring’s iconic faceless crawling children, barking dogs and kinetic dancing figures live on all over the world.

These days Scharf, a grandfather, lives in Los Angeles and divides his time between New York and Brazil, among other locales. Last month he was invited to be part of a public art show in Malaga, Spain, where Picasso was born.

“Growing up in LA in the ’60s profoundly influenced my visual landscape,” Scharf explained in the program guide. “There were bright plastic colors and space age designs everywhere, from coffee shops to car washes…When I moved to NY in the ’70s, it was a very drab place colorwise, and I thought a little brightening up would help a bit.”

Gallery I features Scharf’s whimsical polished bronze sculptures and an appetizing series of paintings of rather singular donuts. One typical title is “Pink Frosted Cruller in Outer Space,” which he did in 2010. No galaxy ever looked sweeter. Adding to the overall aesthetic experience is that the gallery’s false walls were taken down, exposing the room’s stately windows and letting viewers take in the museum’s spacious grounds as well as the art on display—an idea that Scharf had expressed because “he thought the room would look happier,” recounted a grinning Laura Lynch, the museum’s director of education, on a recent tour with the Press.

“The really important thing for me is communicating,” Scharf has said, “and the bigger the audience, the better. I went to art school, took art history, and I want the art elite to be able to see in my work how it’s new but also how it has a tradition within it. I also want people who don’t know or care about art to want to know about art and get inspired in some way.”

Although some visitors may scoff at the idea, Scharf considers himself a traditional painter, according to Lynch, pointing out how he used reflected light coming from the left of the frame to illuminate the central object on the canvas, an aesthetic concept stemming from the Renaissance. In this case, the subject being a dark chocolate glazed donut.

It’s like stepping into a “Wild Style” abstract painting and entering a secret clubhouse that would leave your mom so speechless that she would forget to tell you to “clean up all this junk” before your father gets home from work.

In Gallery II, the white walls surrounding the “Cosmic Cavern” installation came from Scharf’s former studio in Bushwick, showing his artistic process, his evolving lines and paint splashes, plus candid photos of him and his friends. It took him and his crew two weeks to install the Cavern. Scharf had created his “Cosmic Closet” in 1981, supposedly discovering a closet in the apartment he shared with Haring that was filled with junk, which he subsequently drenched with fluorescent paint and lit up by a black light. The idea caught on, eventually taking up shape at P.S. 1 in Long Island City and the 1985 Whitney Biennial, which helped put the East Village art scene on the international map once and for all time.

Here in Nassau, museum-goers daring to explore the Cavern enter a large room the size of a suburban basement filled from top to bottom with an amazing array of “found objects.” There’s a boom box to fill the air with music from the ’80s and a couple of artfully decorated ceiling fans to keep the air moving. Some of the stuff dates back to 1981 and other things are “gems” he just found in the garbage this year, Scharf says.

“In a sense it’s a time capsule,” Lynch explained. “Everyone who comes in here wants to stay here!”

His exhibit culminates in Gallery III with “Pop Renaissance,” consisting of four 33-foot canvases that he originally did in 2001 across the ceiling of the Palazzo Communale in Pordenone, Italy, and now expanded considerably with more dimensions. The work combines religious figures, surrealist motifs, black text, magazine images, swirling paint, sculptural elements, plus the ubiquitous rectangle of a TV. But there’s always a touch of whimsy to Scharf’s art. Pointing to a line of Arabic on one of the panels, Lynch said that it translates into “Best kebabs!”

The second floor of the museum is devoted to Scharf’s urban contemporaries with art work, sketches and even repeated film screenings of Edo Bertoglio’s “Downtown 81,” which features a 19-year-old Basquiat and Debbie Harry as a fairy godmother, Charlie Ahearn’s groundbreaking “Wild Style,” which chronicled the hip-hop cultural explosion that happened when the Bronx blew the East Village away, and Harry Chalfant and Tony Silver’s “Style Wars” historic documentary.

“This [exhibit] is called ‘Glamorous Graffiti,’” said Lynch. “This is not art that’s on the wall or a subway train. These artists started doing public works outside but now they’re framed in the museum.” She said they may have started as “outlaws” in a sense but soon “companies really wanted that urban aesthetic and started bringing it into their products and they started getting commissions.”

And for some, those commissions added up to real money.

There’s only one painting by Basquiat, “Third Street,” done in 1984, but it’s a powerful work, showing his interest in human anatomy, African masks, comic books and language, and conveying the full range of this innovative artist’s imagination. Keith Haring’s “Growing Suite I-V” consists of five color screen prints done in 1988 on Lennox Museum board.

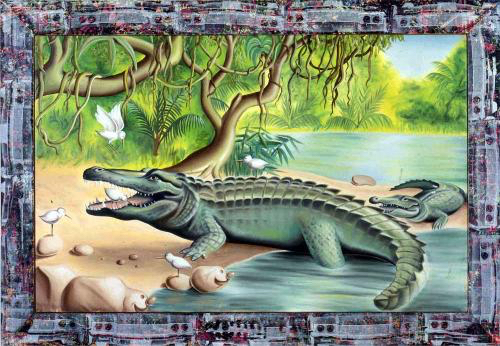

Lee Quinones, considered one of the most influential artists to emerge from the NYC subways, is represented by several pieces, including a very funny take-off on “Sesame Street” with Big Bird and his pals breaking the law, let’s say. Quinones’ “One Million B.C.” is a revealing sketch he did in 1977 for a whole subway car mural, showing the process he undertook. Starting when he was only 13, he was known as “a ninja in the train yards,” because he worked so quietly and quickly in the dark to avoid the MTA cops on patrol in the Bronx, as well as the “conscience on the rails,” because he used his hand-sprayed images and text to convey radical political messages against war, death and violence. His tag was LEE. Two years later he had his first solo show in Rome, and these days his work is included at the Whitney, the Museum of Modern Art and elsewhere.

The show upstairs also includes works by CRASH (John Matso), Toxic (Torrick Ablack), Koor (Charles Hargrove), Futura 2000 (Leonard Hilton McGurr), Dondi (Donald Joseph White), DAZE (Chris Ellis) and NOC167 (Melvin Samuels Jr.). There’s a 2012 piece, “Lotus, Target Black,” by Shepard Fairey, who became famous for his Obama “Hope” poster that he did in 2008, and a very provocative print that the street artist Banksy created in 2003, called “Bomb Hugger,” which shows a girl in a pony-tail and a mini-skirt happily embracing the aerial weapon.

“It freaks out the kids at first,” said Lynch. “It makes you nervous for her!”

The title is ironic, too, considering that graffiti artists used the expression “to bomb” when they meant painting quickly on many surfaces in one area. Scharf will put it in action for several hours on June 19, when he will be outdoors at the Nassau Museum for a performance he calls “KARBOMBZ!” He’ll be spray-painting three automobiles on the grounds so viewers can watch him at work. He’ll also be on hand to sign his new book, “Kenny Scharf: Kolors.”

Nassau County Museum of Art is located at One Museum Drive in Roslyn Harbor, west of Glen Cove Road, just off Northern Boulevard, Route 25A. For current exhibitions, events, days/times, and directions, call (516) 484-9337 or log onto nassaumuseum.org.