By now, Long Island’s elected officials and policymakers should know how best to protect our region’s precious drinking water. After all, they have half a century’s worth of studies to consult. They should understand the problem and what has to be done to solve it.

But apparently that’s not the question.

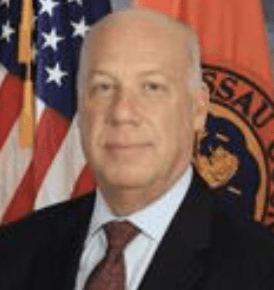

Since Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone’s recently proposed water fee is now as dead as the fish in the Peconic River, a legitimate concern rises from the murky, algae-clogged depths: How do we pay for water protection on Long Island?

This latest ill-fated push for funds, an effort begun in April, was essentially dead on arrival. Suffolk reportedly wanted to create a referendum asking whether residents would support a water quality protection fee of $1 per 1,000 gallons of water used. Policymakers at the state level were supposedly ticked off they weren’t given enough notice about the proposal, while local critics worried about these funds being diverted for other, less green initiatives.

At the time, Paul Sabatino, former deputy Suffolk County executive, said the notion of taxing the water we drink is like taxing the air we breathe. On June 8, Bellone dropped the proposed water fee, saying that he’ll revisit the issue down the road. The rumor mill is saying that his water fee proposal may resurface during the next Suffolk legislative session.

Politicking aside, the environmental and policymaking community seems to be coalescing around sewers, advanced smaller-scale nitrogen removal systems and yet more sewers as the right approach for water protection. Where will the money come from?

The simple answer would be to hike taxes, allowing the region to pay for whatever upgrades are needed. But this is Long Island, where “No Taxes Welcome” should be engraved in stone on the Queens/Nassau border. Residents are right to be wary of additional taxes and fees.

They are already overburdened, especially compared to other parts of the state. And if the federal investigation of the corruption allegedly permeating our local and state governments is any indication, their hard-earned monies aren’t being well spent anyway.

So, how do we address the economics of implementing decades’ worth of strategic plans?

Innovation, it seems, is the key. Why not redirect some of the funds generated by red-light cameras to pay for infrastructure upgrades? Or, if it’s eventually passed by the Suffolk County Legislature, use some of the funds raised through plastic bag ban revenues?

Innovation has driven environmental policy in Suffolk before, fueling public efforts to preserve open space and protect groundwater through real estate fees and quarter penny sales taxes. Those are ideas county voters have repeatedly supported.

Elected officials and municipal bean counters should look for existing taxes and fees that offer ample opportunity to be redirected for a higher, greener purpose. In essence, use the green to pay for green policies.

On the plus side of the balance sheet, New York State got a financial windfall in the wake of the housing crisis, thanks to a huge legal settlement with the nation’s five largest mortgage banks that had been accused of abusive servicing and bad foreclosure practices before and during the Great Recession. New York had joined 48 other states in a federal lawsuit that led to a $25 billion agreement in 2014, reportedly netting around $4.5 billion as its share.

That being said, it wouldn’t be outlandish to redirect some of the money slated for a new Penn Station, Port Authority Bus Terminal or other transportation infrastructure upgrades to finance some vital wastewater treatment. Long Island needs them too, but investment in our transit systems will essentially be shortchanged if we cannot maximize our economic potential through smart residential development. If these settlement funds aren’t legally restricted, they can go a long way toward addressing some of the region’s green woes.

But our region’s environmental limitations, mostly stemming from the lack of sufficient wastewater treatment, prohibit Long Islanders from getting the most out of projects like the Long Island Rail Road double track, which is slated to run from Ronkonkoma and Farmingdale, or the East Side Access tunnel, which will connect LIRR commuters to Grand Central Terminal. These investments could yield true transit-oriented living near the LIRR train stations, but only if Long Island’s commuter and workforce habits shift. If impediments to growth could be properly balanced and reconciled in conjunction with these improvements through sound planning, then the state’s multi-billion-dollar investments may bear fruit sooner.

The reality is that additional growth is going to come to the Island in some shape or form. Whether those who oppose all growth anywhere and anyhow care to admit it, the fate of Nassau and Suffolk counties is tightly connected to the downstate region, driven by our economic powerhouse, New York City. Being so close to one of the largest and most successful metropolises in the country has its share of drawbacks, such as the need to stay competitive in the realms of housing and jobs. But it would be a mistake to stick your head in the sand and pretend that LI doesn’t have to contend with serious environmental issues.

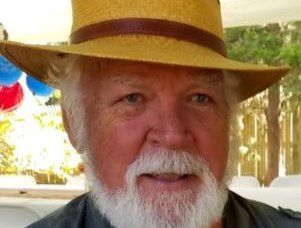

Bob DeLuca, president and CEO of the Group for the East End, a nonprofit advocacy organization based in Bridgehampton, makes a compelling case for some innovative funding mechanisms to help protect Long Island’s environment.

“At some point, there has to be an honest discussion about doing something, not writing more reports,” DeLuca said. To him, funding the necessary upgrades may require an expansion of the East End’s Community Preservation Fund, an additional tax added to real estate transactions in the five East End townships.

“The CPF model can be looked at in other towns that don’t have open space left to protect, but want to protect water quality,” DeLuca said. Currently, his group is working to extend the program to 2050, as well as expand the scope of the CPF fund so that it includes water quality initiatives.

Another idea being explored is creating water quality improvement districts in certain areas of the Island.

“Essentially, it’s like a business improvement district, but for water quality,” DeLuca explained.

Asked about the possibility that these new sewers would spur more unchecked development, DeLuca stressed that local municipalities retain control over land use.

“Much of the sewering is needed for areas that are already built,” he said, adding that the new sewers “don’t allow more growth if the municipalities don’t allow it. People don’t realize that local municipalities put density where the zoning is. They run the town, and put the zoning in place. Period.”

Nassau’s political and fiscal uncertainty, paired with the county’s serious lack of undeveloped open space, limits growth. But Suffolk’s environmental limitations also hamper our prosperity. We have to become innovative in how we fund the expansion of sewers, the replenishment of eelgrass in the southern bays and the reclamation of our coastline.

On Long Island, the economy and the environment aren’t mutually exclusive. Perhaps it’s time we think outside of the box to help both improve.