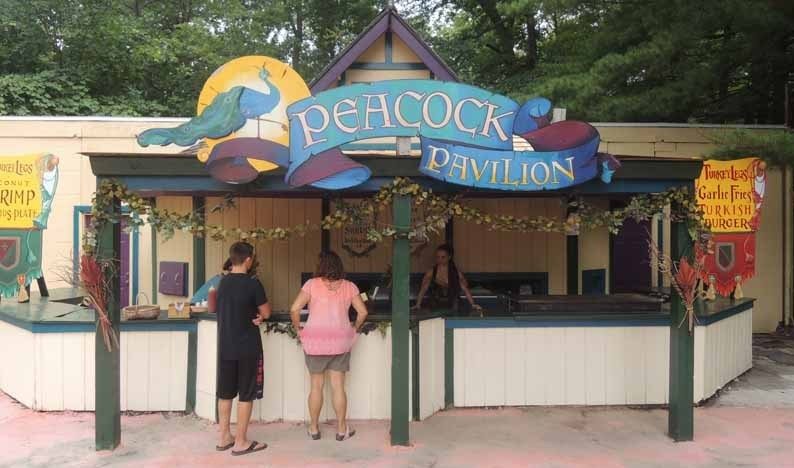

Traveling through the Renaissance Faire in Tuxedo, NY, it is quickly apparent that providing period-specific cuisine was not a top priority. Revelers dined on foods like ye olde burrito—not quite a staple of a 17th century European menu.

Traveling through the Renaissance Faire in Tuxedo, NY, it is quickly apparent that providing period-specific cuisine was not a top priority. Revelers dined on foods like ye olde burrito—not quite a staple of a 17th century European menu.

That’s not to say the food isn’t worth munching on. Chicken wings, turkey legs, the aforementioned burrito and more are all available and at a high quality. But those food items, while delicious and enjoyable, are misplaced in time at a Renaissance Faire. Even turkey legs, which one can imagine a European lord gorging upon at a comically long table, are anachronistic eats as the turkey is a New World bird.

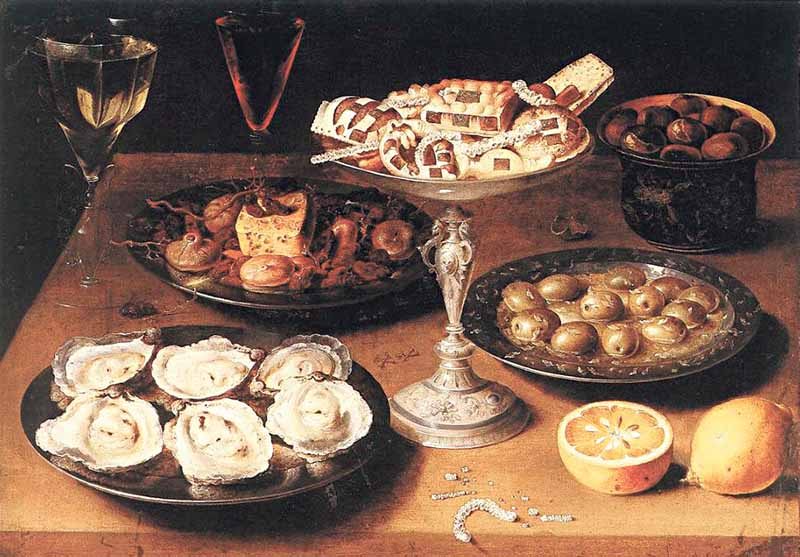

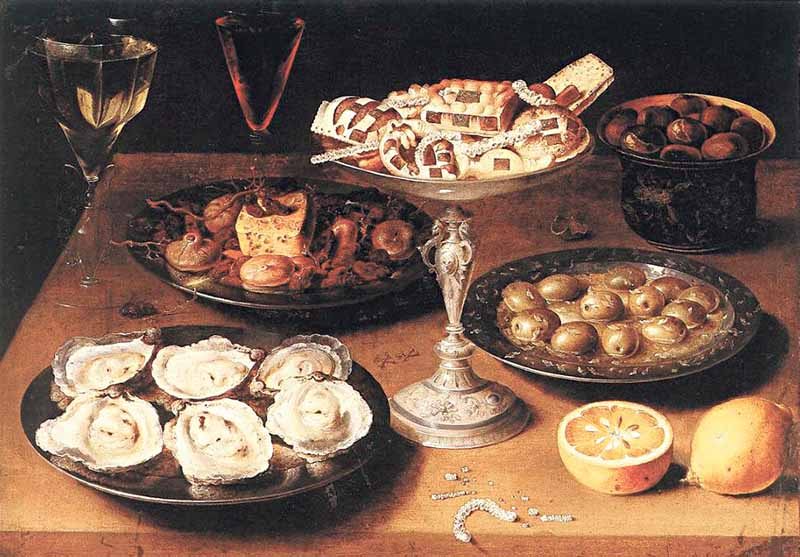

Examining authentic menus from that era, one can come to the conclusion that the Renaissance laid the groundwork for today’s foodie culture. The wealthiest populations enjoyed grand, multi-course meals of gut-busting proportions, featuring hard-to-pronounce ingredients all exquisitely plated and ravenously devoured.

Renaissance eaters loved their small birds—if it flew, it was feasted upon. Birds including blackbirds, woodcock, pheasants, plovers, thrushes, finches and even herons were consumed regularly. And of course, small mammals such as rabbits, squirrels and mice also scurried onto many dinner plates.

In terms of drinkables, the faire featured plenty of beer—and this makes sense as ale was consumed by the gallons in Renaissance Europe. Ale has been made for centuries using only water, yeast and roasted-malted barley. The beverage was often consumed in place of water, as drinking H2O back then was a surefire way to end up dead. Mead, a fermented honey beverage, was also available at the faire and though it was likely available during the Renaissance period, it is more closely associated with Norse mythology.

The Renaissance and Medieval foodie website www.godecookery.com reveals historically accurate dishes and recipes. Some of the dishes named include A Shoulder of Mutton with Oysters, Neats Tongues to Hash (a dish of cow tongue), Carbonado Mutton, Cold Calves Head, Dish of Marrow (small pastries filled with bone marrow) and Potage of Larks (bread pudding with small game birds, beef tongue and lamb broth). Sadly, none of the preceding items had its very own stand at Tuxedo’s Renaissance Faire.

The capon was also a popular bird eaten during that time. For the unfamiliar, a capon is a cockerel or rooster that has been castrated to improve the quality of its flesh—and in some instances, is fattened by forced feeding. A popular dish was Capon Hashe, basically a stew of capon, ox tongue, chestnuts, eggs, bacon, wine and pistachios. The following recipe, reprinted on www.godecookery.com, originally appeared in The Art of Cookery Refined and Augmented, 1654.

How To Hashe A Capon

Roast your capon almost enough, then cut all the flesh from the bones which will mince, and mince it small; put it into a pipkin with white wine and a little strong broth, five or sixe hard yolkes of eggs, with nine or ten chesnuts minced very small, an oxe palate sliced very thin, a little bacon (if it be not rusty) minced small, some powder of saffron, a hand-full of pistaches;

Roast your capon almost enough, then cut all the flesh from the bones which will mince, and mince it small; put it into a pipkin with white wine and a little strong broth, five or sixe hard yolkes of eggs, with nine or ten chesnuts minced very small, an oxe palate sliced very thin, a little bacon (if it be not rusty) minced small, some powder of saffron, a hand-full of pistaches;

stew all these together with the gristles and bones (which will not mince) till it be tender; then put in a large piece of butter, a little vinegar or minced lemmon (if you have it) with a little of the peel, and a little salt; shake it well together and let it not boyl;

then lay thin white-bread tostes in the dish; pour this meat on it, and lay the bones in order about the dish with sippits, barberries, halfe yolks of egges, or greene and what other coloured garnish you fancy.