“The AUMF is now nearly 12 years old. The Afghan war is coming to an end. Core al Qaeda is a shell of its former self. Groups like AQAP must be dealt with, but in the years to come, not every collection of thugs that labels themselves al Qaeda will pose a credible threat to the United States. Unless we discipline our thinking, our definitions, our actions, we may be drawn into more wars we don’t need to fight, or continue to grant Presidents unbound powers more suited for traditional armed conflicts between nation states. So I look forward to engaging Congress and the American people in efforts to refine, and ultimately repeal, the AUMF’s mandate.” – President Barack Obama, May 23, 2013.

US fighter jets and drones circled above a terror training camp in Somalia last March as scores of presumed militants celebrated a graduation ceremony.

Of immediate concern to US officials was what the alleged Al Shabaab militants planned to do next. Apparently in possession of evidence that trainees were plotting an attack on US troops and allies in the region, US officials decided a preemptive strike was in order.

After the dust settled, the Pentagon estimated that 150 alleged militants were killed—just like that.

That the United States targeted a camp in Somalia is not surprising. What later astonished watchdog groups, however, was the death toll. The London-based nonprofit Bureau of Investigative Journalism classified these strikes as the deadliest ever recorded by the organization.

This recent military operation—a lethal combination of unmanned drones and piloted warplanes—is just one of countless missions that have been carried out against an amorphous array of terror groups and militants spanning more than a dozen countries since al Qaeda crashed planes into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on Sept. 11, 2001. Lately, the most notorious target is the so-called Islamic State, or ISIS.

For 15 years, the United States has been waging a war not against a single nation but an enemy that has metastasized so rapidly most Americans would be excused for being unable to identify the US’s many post-Sept. 11 foes. That’s because what began as an initial response to al-Qaeda’s involvement has morphed into an open-ended conflict against myriad groups spread out across the Middle East and Africa, all in the name of the “War on Terror”—the longest battle in the nation’s history: 5,482 days and counting as of this publication. Over that period, 4,504 US soldiers have died in Iraq, and 2,384 US soldiers have perished in Afghanistan, according to icasualties.org, which tracks military conflict deaths. It has been costly in other ways, too. A Congressional Research Service study released in July 2014 estimated that US taxpayers have paid more than $1.6 trillion to wage it.

Yet Congress, the only branch of government empowered by the Constitution to declare war, has yet to hold a single vote on the Obama administration’s two-year-old assault on ISIS, nor for that matter, on the many attacks it’s directed against an array of militant groups around the globe. By contrast, the House Select Committee on Benghazi spent more than $7 million over two years investigating the embassy attack that killed four Americans.

Through its inaction, the Republican-dominated Congress—which has lambasted Obama for his alleged abuse of executive power on other issues, such as immigration and gun control—has all but endorsed Obama’s ISIS policy by granting him free reign to unilaterally bomb countries unrelated to the Sept. 11, 2001 aggression and openly engage in proxy wars.

Congress may not be prepared to act, but make no mistake, its silence is not going unnoticed.

On the fifteenth anniversary of the 2001 Authorization to Use Military Force (AUMF), the joint resolution which granted then-President George W. Bush the initial power to mobilize US Armed Forces against those responsible for destroying the World Trade Center, it is worth analyzing how the United States arrived at its current state of perpetual war.

“Of the issues which are not being discussed, this is one of the most important, because we are setting a precedent here for the next generation,” Bruce Ackerman, a noted Yale Law School professor and prolific author, tells the Press. “And shall the president unilaterally use force, and shall we depend on the wisdom of a single person to make war—this is what the American Revolution is about.”

THE DRUMS OF PERPETUAL WAR

From a 10-day span beginning in late August, the US bombed Al-Shabaab militants in Somalia; ISIS in Libya, Syria and Iraq; and al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula in Yemen. If nothing else, the strikes—touted in press releases from US Central Command on MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa, Florida and US Africa Command in Stuttgart, Germany—provide a revealing, albeit limited, glimpse into US military deployments.

From Aug. 30 through Sept. 8 alone, American forces have conducted more than 120 strikes in Syria, Iraq, Libya and Somalia, killing 15 alleged militants.

Dominating the news cycle in recent weeks, however, has been the acrimonious presidential horse race between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, conspiracies regarding Clinton’s health, Trump’s unchallenged claims that he opposed the Iraq War (which he actually supported), and debates surrounding Russian President Vladimir Putin’s assumed bravado, which if you haven’t been paying attention (how could you not?), was provoked by Trump’s high praise of the former KGB master spy.

On the same day that Clinton’s falling ill during a 9/11 anniversary memorial event at Ground Zero made headlines around the world, U.S. Africa Command conducted four strikes against ISIS positions in Libya, bringing to 142 the number of air strikes since the US-led operation commenced Aug. 1.

What’s been absent from the coverage is this: The bombings in Iraq, Syria, Somalia and Yemen all stem from the AUMF vote on Sept. 14, 2001, three days after 9/11.

On that day, Congress voted 420-1 in favor of the law after rejecting an earlier version that would have given the president unprecedented powers “to deter and preempt any future acts of terrorism or aggression against the United States.”

The approved 2001 AUMF stipulates:

“That the President is authorized to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons.”

Prof. Ackerman believes Obama has so overstepped the 2001 authorization that his policies more closely resemble the initial AUMF that Congress rebuffed.

“President Bush might have made an unwise decision, might not, but he followed the law, both in Afghanistan and Iraq,” Ackerman, an admitted liberal, insists. “President Obama is not.”

Since Sept. 18, 2001 when Bush signed the joint resolution into law, the 2001 AUMF has been invoked to justify every action from borderless wars, ubiquitous drone strikes, indefinite detention of alleged militants, the extrajudicial killings of US citizens, domestic wiretapping and bombings of various organizations that didn’t even exist when terrorists flew two commercial airliners into the World Trade Center, one into the Pentagon, and attempted to crash another into either the White House or US Capitol before a passengers’ revolt sent it plumetting into a field in Shanksville, Penn., on Sept. 11, 2001.

A decade-and-a-half later, the War on Terror has expanded dramatically, and along with it, the interpretation of the 2001 AUMF. Yet America is no closer to ending the War on Terror than when it began, and this current state of endless warfare is prompting serious questions about the legality of the ISIS war and whether safeguards are in place to prevent a single person—Obama, or his successors—from continuing America’s perpetual war.

There have been a few bipartisan efforts to repeal the 2001 AUMF and replace it with an ISIS-specific authorization, but such measures have failed.

Despite their inability to force a vote, the minority in Congress proposing change has been vocal.

“We have seen the US send more and more troops to Iraq and Syria, and Congressional leaders aren’t even batting an eye,” said Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Ma.) at a press conference in the capitol this May.

“Make no mistake,” he continued, “we are expanding our military footprint in these conflicts. We are putting more Americans in harm’s way. We are spending unlimited amounts of taxpayer dollars…and we are engaged in endless wars that have no endgame in sight.”

“I am among those who do not agree that the AUMF…is a solid foundation,” added Rep. Scott Rigell (R-Va.) as he called on House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) to hold an ISIS AUMF vote. “To me, it’s crumbling; it’s not legally binding or standing in any respect.”

In June vice presidential candidate Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va) drafted two amendments to an annual defense appropriation bill that would sunset the 2001 AUMF two years after the new administration takes office.

Similarly, Rep. Barbara Lee (D-Calif.), the only member of Congress to oppose the 2001 AUMF, has introduced an amendment that would repeal the law 90 days after its defense funding expired. So far all efforts to persuade members to pass a new AUMF have failed.

Complicating matters is the Obama administration’s opinion that the 2001 AUMF provides legal authority for his war on ISIS. Since its outset on Aug. 8, 2014, this battle has cost $8.7 billion—an average of $12.1 million per day, according to the Congressional Research Service. The administration argues that fighting ISIS is covered by the AUMF’s mandate. But ISIS has not been affiliated with al Qaeda since 2014.

Despite the administration’s view that the 2001 AUMF, as well as a 2002 version—which gave Bush the authority to invade Iraq—can be applied to present-day threats, Obama proposed his own AUMF. But it didn’t take long for Republicans to criticize it as too restrictive and Democrats to argue that it’s overly broad. Even without it, the White House intends to bomb ISIS positions in Iraq, Syria and now, Libya.

While giving testimony March 2015, Obama administration officials told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that a new authorization is not necessary to legally battle ISIS.

Essentially, a new AUMF would be a symbolic gesture, created simply for the purpose of showing a united front against ISIS, US Secretary of State John Kerry told committee members at the hearing.

“The President already has statutory authority to act against ISIL, but a clear and formal expression of your backing would dispel any doubt anywhere that Americans are united in this effort,” he explained.

For his part, Obama has repeatedly said he’d like Congress to sunset the 2001 AUMF eventually. But when he proposed his ISIS AUMF, he only stipulated that the 2002 version would be repealed, not its more controversial predecessor.

“Unless we discipline our thinking, our definitions, our actions, we may be drawn into more wars we don’t need to fight, or continue to grant Presidents unbound powers more suited for traditional armed conflicts between nation states,” Obama said in a speech at the National Defense Institute in May 2013.

Obama added: “So I look forward to engaging Congress and the American people in efforts to refine, and ultimately repeal, the AUMF’s mandate.”

Since August 2014, three American service members have died fighting ISIS. Meanwhile, Congress has yet to hold a single vote, let alone a debate, on the merits of sending the nation’s soldiers to yet another war.

That’s the exact quagmire Rep. Barbara Lee was trying to avoid when the California Democratic Congresswoman delivered the lone vote opposing the 2001 AUMF 15 years ago.

MISSION CREEP

Sitting at the National Cathedral in Washington, DC, during a special memorial service on Sept. 14, 2001, she contemplated how she’d vote.

She had two choices: follow her gut and oppose the 2001 AUMF joint resolution or support the measure as a demonstration of American unity against terror.

As she considered her options, Lee listened as speakers honoring the national day of mourning held at the historic cathedral attempted to heal a wounded nation.

Rev. Nathan D. Baxter, dean of the Washington National Cathedral, found comfort in prayer. With the drumbeats of war sounding ever louder in the halls of Congress while the rubble at Ground Zero still smoldered, he remarked on the tough choice entrusted to America’s leaders.

“Let’s us now seek that assurance in prayer for the healing of our grief-stricken hearts, for the souls and the sacred memory of those who have been lost,” Baxter implored that day. “Let us also pray for divine wisdom as our leaders consider the necessary actions for national security. Wisdom of the grace of God that as we act, we not become the evil we deplore.”

It was as if he was speaking to Lee.

“That as we act, we not become the evil we deplore.”

“It was at that moment I said, ‘Yeah, you know, if we pass this resolution, there is no end in sight, and this could lead to wars everywhere in the world,’” Lee tells the Press.

That very same day, she went to the House floor and delivered the sole speech opposing the White House’s proposal.

“This unspeakable act on the United States has forced me, however, to rely on my moral compass, my conscience, and my God for direction,” an emotional Lee told fellow lawmakers. “September 11th changed the world. Our deepest fears now haunt us. Yet I am convinced that military action will not prevent further acts of international terrorism against the United States. This is a very complex and complicated matter. Now this resolution will pass, although we all know that the president can wage a war even without it.

“However difficult this vote may be, some of us must urge the use of restraint,” she continued. “Our country is in a state of mourning. Some of us must say, ‘Let us step back for a moment, let’s just pause just for a minute and think through the implications of our actions today so that this does not spiral out of control.’ Now I have agonized over this vote, but I came to grips with it today, and I came to grips with opposing this resolution during the very painful, yet very beautiful memorial service. As a member of the clergy so eloquently said: `As we act, let us not become the evil that we deplore.’”

The resolution passed 420-1 on Sept. 14. Four days later President Bush signed it into law.

Following her vote, a few of Lee’s colleagues wrapped their arms around her as a show of support. Sure, they disagreed with her decision, but they respected her for following her convictions.

“It was difficult,” Lee acknowledges in a recent phone interview. “It had nothing to do with my anger and belief that we needed to bring those who perpetrated this horrific attack to justice.” Lee did not personally lose anyone on 9/11, but her chief of staff’s cousin was killed when Flight 93 crashed in Shanksville.

“I mulled over it. It was like, ‘Okay, is it easier to say: Go along with the flow and be part of the unified response? Or to really try to uphold my Constitutional duty, and say, ‘Let’s step back for a minute and make a rational decision?’” she continues. “Let’s determine how to react without leading to more terror, more violence, more war. Three days after 9/11, that was not the time to do this.”

Years later Lee remains convinced she made the right decision. She cites a report from the non-partisan Congressional Research Service, which notes that both presidents Bush and Obama have publicly referenced the AUMF at least 37 times to justify US military action.

The same report found that the AUMF has been applied to various levels of military action in 13 countries: the more well-known battlegrounds of Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Somalia, Syria, Libya and Guantanamo Bay, Cuba—as well as those that don’t necessarily provoke immediate connections to the War on Terror—Djibouti, Kenya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Georgia and the Philippines.

As the war has progressed and the tactics have changed, so too has the executive branch’s interpretation of the law.

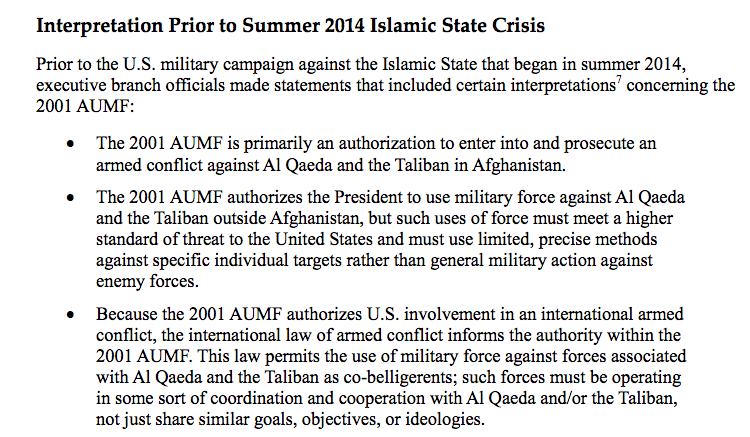

The Congressional Research Service discovered three varying interpretations of the 2001 AUMF from Bush and Obama administration officials prior to the war on ISIS. The legal understanding evolved from “primarily an authorization to enter into and prosecute an armed conflict against al Qaeda and the Taliban in Afghanistan” to use force outside Afghanistan on specific individual targets when a “higher standard of threat” was posed. The interpretation was later defined so broadly that the AUMF was understood to include forces “associated” with al Qaeda and the Taliban, the report noted.

The CRS report does not paint the whole portrait of how the 2001 AUMF has impacted policy-making because its mandate was limited to only examining unclassified reports prepared for Congress.

One such operation not made public until the Obama administration was pressured by a federal court to reveal its so-called “Drone Memo” was a drone strike in Yemen on Sept. 30, 2011. The strike killed Anwar Al-Awlaki, a US citizen-turned-radical cleric and alleged leader of al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).

Before Al-Awlaki could be assassinated, the Obama administration made sure it had legal authority to act.

Gen. David Barron, then the acting assistant attorney general, argued in the July 16, 2010 memo that the AUMF “clearly” authorized the president to use “necessary and appropriate” force against al Qaeda, which, Barron determined, encompassed al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

“[A] decision-maker could reasonably conclude that the AQAP forces of which [Al-Awlaki] is a leader are ‘associated with’ [al Qaeda] forces for purposes of the AUMF,” the memo reads.

Thus, that day Al-Awlaki’s death warrant was essentially sealed.

The same strike also killed Samir Khan, an al-Qaeda propagandist who spent his teenage years on Long Island in Westbury, where he wrote for his school newspaper. Government officials have said that Khan was a bystander and was not targeted by the United States.

A redacted version of the memo only came to light after The New York Times and the American Civil Liberties Union sued for its release.

“And shall the president unilaterally use force, and shall we depend on the wisdom of a single person to make war—this is what the American Revolution is about.”

The memo offered a rare peek into the US’s drone war, including what many human rights groups and journalists had long reported: the CIA’s direct role in running the government’s program.

Drone strikes have been the hallmark of the Obama administration—and the 2001 AUMF has served as legal authority for perpetrating strikes outside of war zones in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Of the 424 strikes conducted in Pakistan since 2004, 373 have been carried about by the Obama administration, according to The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, which tracks drone strikes in Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia and Afghanistan. Drone strikes have also been responsible for hundreds of civilian deaths, according to the BIJ. US officials recently claimed that drone operations have killed between 64 to 116 civilians, prompting criticism that the government was low-balling the civilian death toll.

“[The 2001 AUMF]’s so broad that it’s being used for military action and other forms of military activity…that has nothing to do with 9/11,” Lee says.

Lee may have been alone on Sept. 14, 2001, when she voted against the 2001 AUMF, but she’s not acting solo anymore.

RISING TIDE

Back in May, U.S. Army Captain Nathan Smith sued President Obama on the grounds that the ISIS war is illegal.

The case is still making its way through the courts, but the fact that a deployed service member is suing his commander-and-chief has given new momentum to the cause.

Smith, who joined the Army in 2010, is by no means a pacifist. Fighting ISIS is the right thing to do, he insists, but he’s just not sure that what he’s being commanded to do is legal under the Constitution.

Smith’s challenge centers around the 1973 War Powers Resolution enacted after the Vietnam War to ensure that future presidents do not usurp Congress’ authority. The resolution stipulates that unless Congress authorizes war within 30 days, the president has up to 60 days to pull armed forces out of a conflict zone.

Despite Congress’ failure to decide whether the United States should fight ISIS, nearly 4,400 troops have been deployed to Iraq and Syria. Smith is stationed at the command center in Kuwait at the center of the war on ISIS.

“He takes his obligation to protect and defend the Constitution of the United States seriously,” says Ackerman, the Yale professor. “And what does he have? A set of informal remarks attributed to one or another administration source which shift over time.”

Smith got in touch with Ackerman after he read the professor’s Aug. 25, 2015 article in The Atlantic arguing that, given Congress’ acquiescence, perhaps the courts could intervene. But the only piece missing from that equation was someone who would have standing to sue: a US soldier.

“Existing case law establishes that individual soldiers can go to court if they are ordered into a combat zone to fight a war that they believe unconstitutional,” Ackerman says.

Enter Smith.

“We’re at a crucial turning point,” Ackerman observes. “President Obama himself has repeatedly stated that it’s [the 2001 AUMF] obsolete and the like, but he just keeps on using it. This lawsuit marks a critical turning point. If the courts don’t take this case seriously and actually take the law seriously, but stay on the sidelines, I have no doubt that the next president, whoever he or she may be, will use President Obama’s precedent as the basis for unilateral lawmaking, whenever he or she—in good faith—believes it will deter attacks on the United States.”

The current debate has little to do with whether fighting bloodthirsty death cults like ISIS is justified, though some people might disagree with the tactics. Of concern is whether the 2001 AUMF has given the executive branch carte blanche to wage war in America’s name wherever—and however—the president sees fit.

The inherent issue with the AUMF is that it was formed in the wake of 9/11, when the threat posed to the nation was al Qaeda and the Taliban. None of the emerging terror groups—al Shabaab, AQAB and ISIS—had a role in the Sept. 11 attacks. To resolve this discrepancy, Obama administration officials argue that such groups are judged based on their current and historical activities. Those who would like to see a new authorization to combat ISIS insist that passing a measure specifically targeting a certain group would resolve the ambiguity.

“The determination that a particular group is an ‘associated force’ is made at the most senior levels of the U.S. government, following reviews by senior government lawyers and informed by departments and agencies with relevant expertise and institutional roles, including all-source intelligence from the U.S. intelligence community,” said Stephen W. Preston, general counsel to the Department of Defense, in his testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in May 2014.

Simply sharing the same beliefs as al Qaeda, he asserted, is not enough to deem a group an “associated force.”

Preston delivered his remarks prior to the administration’s bombing campaign against ISIS in Iraq and later in Syria. At the time, the law was being applied to military operations in Afghanistan and the continued detention of prisoners in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. AUMF had also been invoked to combat AQAP in Yemen and for capture-or-kill operations in places like Somalia and Libya.

Perhaps the most dramatic capture mission occurred in October 2013 in Libya, when US Special Forces dragged Abu Anas al Libi, one of the FBI’s most wanted men, out of his car and took him into US custody. Al Libi, who had a $5-million reward on his head, had been indicted in federal court in 2000 for allegedly planning several US embassy bombings that killed more than 200 people. Al Libi, who had been in poor health, died while awaiting trial in New York.

Such is the scope of the 2001 AUMF that the United States can send special forces into a country it is not in direct hostilities with and capture a suspected terrorist.

Like Yale’s Ackerman, Marjorie Cohn, professor emerita at the Thomas Jefferson School of Law in San Diego, Calif., has been critical of Obama’s interpretation of the 2001 AUMF.

“Only Congress has the Constitutional power to declare war,” Cohn tells the Press. “Then the president can lawfully wage war. But the UN Charter prohibits the use of military force except in self-defense. So even if Congress declares war, it could be illegal under the UN Charter if not carried out in self-defense.”

So if Congress is so bullish about fighting ISIS, why not then approve one of the several authorization versions that have been proposed and put an end to the debate about the scope of the executive powers?

“We should,” says Lee. “The president sent one over over a year and a half ago. I don’t support what he sent over because it didn’t repeal the 2001 authorization, but we should at least try to amend it, debate, and members should vote up or down.”

Days before the anniversary of the 2001 AUMF vote, Rep. Lee once again took to the House floor to deliver a harsh rebuke of Congress.

“The American people and Congress deserve to know what’s being done in their name. Sadly Congress has been missing in action,” she said. “It’s unacceptable that our brave servicemen and women are facing snipers and mortar rounds, but Congress can’t even muster the courage to debate the war that we are asking them now to continue to fight—it’s just plain wrong.”

“There is a consensus in Congress that we should be fighting the war,” adds Ackerman. “It’s just that all things considered, nobody wants to take the blame if it fails. [But] that’s just what the Constitution demands.”

And so America’s longest war rages on.

(Featured photo credit: Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)