On the campaign trail Donald Trump often called Obamacare a “disaster” and promised to repeal it. Now that he’s become the president-elect, the medical and economic implications for Long Island could be profound if he fully carries it out.

Some 20 million Americans gained health insurance for the first time through the Affordable Care Act (ACA). In our area, more than a quarter of a million people might lose their coverage. That cutback could ripple through our hospital system, as this population becomes older and more vulnerable to disease and has nowhere else to turn but the emergency room.

“It was supposed to be something that society was willing to pay for in order to get to a point where we have better national health,” explains Professor Debra Dwyer, a health economist at Stony Brook University in the College of Engineering who specializes in public policy. “What we’re doing if we repeal it is take a step backwards. We’d be going back to the haves and the have-nots.”

Meanwhile, Trump has already taken two steps back from his radical rhetoric: He’s said he now supports the requirement that people with pre-existing conditions, such as diabetes or cancer, could not be denied health insurance, and the provision that dependent children up to the age of 26 remain under their parents’ plans.

But the president-elect’s recent selection of Rep. Tom Price as secretary of health and human services is a six-term Republican congressman from Georgia who’s been perhaps the ACA’s staunchest opponent, which all but guarantees Obamacare’s dismantling.

It’s too soon to know what Trump or the incoming Republican Congress will replace Obamacare with, but it’s not too early to discuss what’s at stake: the capability of health care providers and local hospitals to provide adequate coverage for patients, the Island’s means of effectively tackling its unremitting heroin epidemic, and the sustainability and future of the region’s health care economy overall—which grew by 25,000 jobs since the law was passed, with 218,000 currently employed within the health care industry throughout Nassau and Suffolk counties, according to the New York State Department of Labor.

New York State has expanded the eligibility standards so more New Yorkers could qualify for Medicaid, and the state has set up subsidized exchanges for those who could not afford to buy health insurance through private insurers. To date, more than 3 million New Yorkers have health insurance through the state’s health care exchange, including more than 334,000 living in Nassau and Suffolk counties.

“If the Affordable Care Act is repealed, these folks on the exchange will once again be priced out of the market, leaving many ending up in the emergency room with acute problems,” says Dwyer. “And because they can’t pay, who foots the bill but the hospitals?”

The cutback would definitely have an economic impact here.

“Healthcare is big on Long Island,” explains Dwyer. “We were expecting a boom… We have a ton of physical therapists. That’s not going to be covered.”

Hospitals were bearing the brunt of cost savings under the ACA’s provisions to improve patient care. But if they experience a large influx of sick people without insurance coming to their emergency rooms, they’ll lose more revenue.

“When hospitals and doctors face fewer patients who are insured, they make less. That’s not rocket science,” Dwyer continues. “Yes, it’s going to have a negative impact on Long Island.”

Under federal law, hospitals are mandated to treat anyone who shows up at an emergency room regardless of their ability to pay. Uncompensated care adds debt to the hospitals’ bottom line, which can create a severe strain, notes Janine Logan, senior director of communications and population health at the Nassau-Suffolk Hospital Council, which represents all Long Island’s 23 hospitals including Northwell Health (formerly North Shore-LIJ Health System) and Catholic Health Services’ facilities.

Logan doubts there would be a full repeal “because you’re going to throw millions and millions of people off insurance. You would absolutely destabilize the insurance market [and] the hospital market. There’s a lot of ramifications to this.”

Her hospital council understands the pluses and minuses of working with the Affordable Care Act because it’s one of three so-called navigator agencies set up on Long Island by the New York State of Health Marketplace that offers low-cost coverage. According to estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau, the uninsured rate on Long Island was 10.5 percent in 2013, and has since dropped to under 7 percent, according to New York State Department of Health’s 2016 Open Enrollment Report.

“We’ve seen the benefits of getting people into affordable health insurance plans,” says Logan, noting that the program is currently open for enrollment until the end of January 2017.

Unlike some other states, New York runs its own program. As a result, Logan says, “We’ve always been in a little bit better situation. We were able to take the increased Medicaid matching funds money available through the federal government. That’s why more people have been insured here.”

She admits that there are “certainly” parts of Obamacare that need to be tweaked: “We’re happy to work with the new administration about what would or would not work.”

“Everybody acknowledges that there are certain problems with the Act,” explains Terry Lynam, senior vice president and chief public relations officer at Northwell Health, the largest employer on Long Island as well as the largest private employer in New York, with more than 61,000 employees. Three years ago Northwell launched CareConnect, its own health insurance plan, which ranks fourth in state marketplace enrollees Island-wide.

“We’re a provider and an insurer,” Lynam explained. “As an insurer, we’ve seen problems with the payment methodology that the government put in place, resulting in insurers getting out of the exchanges because they get penalized financially. In 2017, we will have to pay U.S. Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services $100 million. In essence it’s a tax.”

One big unanswered policy question is: What happens to the Obamacare mandate that everyone have health insurance?

“The mandate is what’s helping to fund the subsidies,” says Lynam. But he notes that the tax penalty for not complying is “not that significant,” so many young and healthy people in their 30s are “just kind of rolling the dice in that regard.”

Because this demographic isn’t enrolling in the exchanges in the numbers that were anticipated, premiums have gone up on average nationwide by more than 20 percent, and that’s what has fueled consumers’ opposition to the act, prompting Trump to call it a “disaster” on the stump to the delight of his crowds.

“The insurance industry and the hospital industry agreed to cost reductions and restrictions in order to help fund the law,” explains Logan of the Nassau-Suffolk Hospital Council. “For insurers, agreeing to cover people with pre-existing conditions is costly, but the promise of millions of newly insured lives offset that cost. For hospitals, the industry agreed to enormous cuts in uncompensated care reimbursements because of the promise of millions of newly insured. Rather than no reimbursement for these people for healthcare services rendered, coverage now provides reimbursement.

“Without mandated, affordable coverage for everyone, the uninsured will turn to the ERs again, and this will in turn drive up premium costs for those who are insured,” predicts Logan. “To keep the provision that insurers cannot deny coverage to those with pre-existing conditions, it has to be funded or offset in some way. Any revised plan will have to deal with this dilemma.”

In the meantime, the hospital industry has been consolidating rapidly, notes Lynam.

“You rarely see stand-alone hospitals because they just can’t survive on their own,” he says. “You’re seeing larger health care systems like ours get larger.”

Northwell has been expanding its outpatient practices—such as its urgent care centers—throughout the metropolitan area, and it now has 550 locations. One factor driving this change has been the shrinking health-care dollar. According to Lynam, Northwell Health has seen its Medicare reimbursements reduced by more than $2 billion in the last three years.

“Health care is not going anywhere,” says Lynam. “People still need care regardless of whether the Affordable Care Act is in place or not. From the political standpoint, you would think that because so many people have gotten coverage as a result some accommodations are going to have to be made for those people.”

Lisa Tyson, director of the Long Island Progressive Coalition, calls denying millions of Americans health insurance “a travesty.”

“In New York State, ACA covers over 2 million people,” she says. “This state has worked to ensure that the program is successful and helps people obtain quality affordable health insurance. Rather than repealing the ACA nationally, Trump should take the program changes that New York State has done and implement them in other states.”

“We already were pretty generous with Medicaid prior to the Affordable Care Act,” adds Professor Dwyer, the Stony Brook University health economist. “So all those subsidies for people who couldn’t afford it on the exchange—all of that is going to go away, which is really scary.”

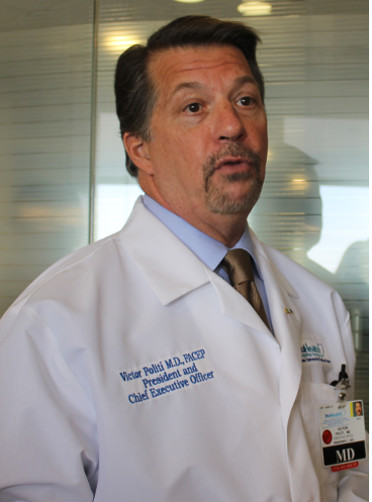

Current funding for Medicaid and Medicare is about 20 percent of the federal budget, according to Dr. Victor Politi, president and chief executive officer of the NuHealth System, aka Nassau Health Care Corporation, which operates the Nassau University Medical Center in East Meadow.

“We are a safety net hospital. We provide medical care to the underserved, and those persons who cannot afford insurance,” explains Politi. “We are mission-driven. We want to treat those patients. Other hospitals are required to receive under-insured patients in their emergency rooms, but we receive them for follow-up care.”

Politi says that the repeal of Obamacare could ultimately result in his hospital receiving less federal reimbursement for patient care—and NUMC already operates annually on a deficit.

Right now, the current system is providing care to the needy population through expanded Medicaid and New York’s exchanges. Politi admits that without government support, hospitals will “take the hit for the cost of that care.”

His facility needs help to pay for the uninsured so he can “keep our doors open.” Medicaid alone is hardly enough. Noting that the East Meadow hospital has 530 beds and 3,500 employees, he says, “We’re a major employer in Nassau and we’re also a major critical infrastructure. No matter what the disaster is, this is the hospital.”

NUMC has a level one trauma center, a well-regarded burn center, plus a methadone clinic and an emergency communications command center for firefighters and police.

He’s not sure what Obamacare will look like after Trump occupies the White House, but he is confident of what NUMC is going to do.

“We’re not going to turn away people,” says Politi. “If you show up at my hospital, whether you have insurance or you don’t, we’re going to take you in and we’re going to give you the top-quality care.”

It’s no secret that Long Island has been at the epicenter of the opioid and heroin crisis, as hundreds of people have died from overdoses. Repealing ACA could have a direct impact on addiction treatment, warns Jeffrey L. Reynolds, president and CEO of the Family and Children’s Association.

“The ACA eliminated some barriers to care, especially for people under the age of 26—a group disproportionately affected by substance use disorders—who have been allowed to remain on their parent’s insurance,” says Reynolds. “Even if Trump doesn’t mess with that provision of the law or the ban on pre-existing condition coverage limitations, 16.4 million Americans got coverage thanks to the ACA. If you apply national averages, at least 10 percent of those folks have a substance use disorder. Do we really want to resurrect barriers to care for 1.64 million Americans who are struggling with a costly, potentially fatal, yet treatable disease?

“As January rolls around and ACA winds up on the table, along with other important discussions, one thing is certain: From this crisis, a massive movement of young people in recovery and families impacted by addiction have emerged—and they’ll be intently watching both President Trump and Congress and holding them accountable,” he continues.

Given all the unknowns, it’s hard to find a bright spot for businesses here, but Kevin Law, president and chief executive officer of the Long Island Association, a not-for-profit lobbying group, says that if the repeal lifts the mandates that employers have to cover their workers, it might save them some money. But there could be more cause for concern in New York.

“If changes to the ACA creates a budget hole for the state, will they then seek to raise taxes on businesses to plug the gap?” he asks.

That remains to be seen.

Compared to other developed countries, the United States has a long way to go to improve the health of all Americans, not just the wealthiest. Obamacare was just a step in that direction.

“We really rank on the bottom in terms of any health indicator you want to look at,” says Stony Brook University’s Dwyer, citing rates of infant mortality and chronic disease. “It doesn’t take a Ph.D in economics to figure out that we’re not efficient. We spend way too much and we don’t have anything to show for it.”

She calls our health care system irrational rationing.

“If you can pay for it, you get it; if you can’t, you don’t,” explains Dwyer. “Whereas in other countries, it’s a different mechanism. You’re going to give it to people who really need it so that they’re healthier, and you’re not going to have a lot of unnecessary care. The goal is to maximize population health. Here we clearly don’t have that goal, because if we did, we wouldn’t have the outcomes that we have.”

And that outcome may only get worse in the years to come.

—With Rashed Mian and Christopher Twarowski