If journalism is the first draft of history, then an entertaining memoir written by a hard-hitting journalist like Edward Hershey must be the second, third or fourth draft. It’s a revealing personal history of post-war America that lets us look over his shoulder as he relives what he experienced firsthand when the news was breaking and he had deadlines to meet.

Thanks to his new book, The Scorekeeper, we’re there with Hershey as he covers the Attica prison debacle, the Son of Sam serial killings and the costly vendetta of a special state prosecutor, Maurice Nadjari, a former Suffolk County chief assistant DA who managed to spend $14 million to “clean up corruption” in New York but gained “not a single major conviction.”

Hershey was in Garden City in 1973 when Newsday decided to start covering the city that so many of its readers had left behind when they moved to Long Island. Until then, the Long Island paper of record only covered New York’s sports teams, or reviewed Broadway shows. It surrendered hot city stories to local TV news or the big city papers. Otherwise the copy desk would rewrite wire service stories. The disconnect didn’t sit well, especially if the reporters were doing the reverse commute, unlike their suburban readers.

“As much as we valued the journalism Newsday allowed us to pursue,” Hershey wrote, “many of us saw Long Island as a dull, stultifying sprawl of cookie-cutter homes occupied by white Democrats-turned-Republicans who clogged freeways and shopped in climate-controlled shopping centers, strip malls filled with chain stores, and fast-food restaurants.”

Born in 1944, he grew up in Brooklyn along Ocean Parkway. As he says, his career touched fame more than achieved it, “a life less about making history than footnoting it.” It will be a familiar tale to many Long Islanders with Brooklyn roots. Hershey went from watching the Brooklyn Bums at Ebbets Field to becoming a sportswriter covering the Yankees spring training in Florida.

He profiled Arthur Ashe, co-wrote a book with the Mets’ Cleon Jones, and interviewed Mickey Mantle, Joe Namath, Wilt Chamberlain and Billie Jean King, to name a few sports legends. Not bad for a self-proclaimed klutz who admittedly sucked at stickball. Hershey took his ineptitude off the field and volunteered to be his Little League’s official scorer, which lay the foundation for his future in getting the facts straight.

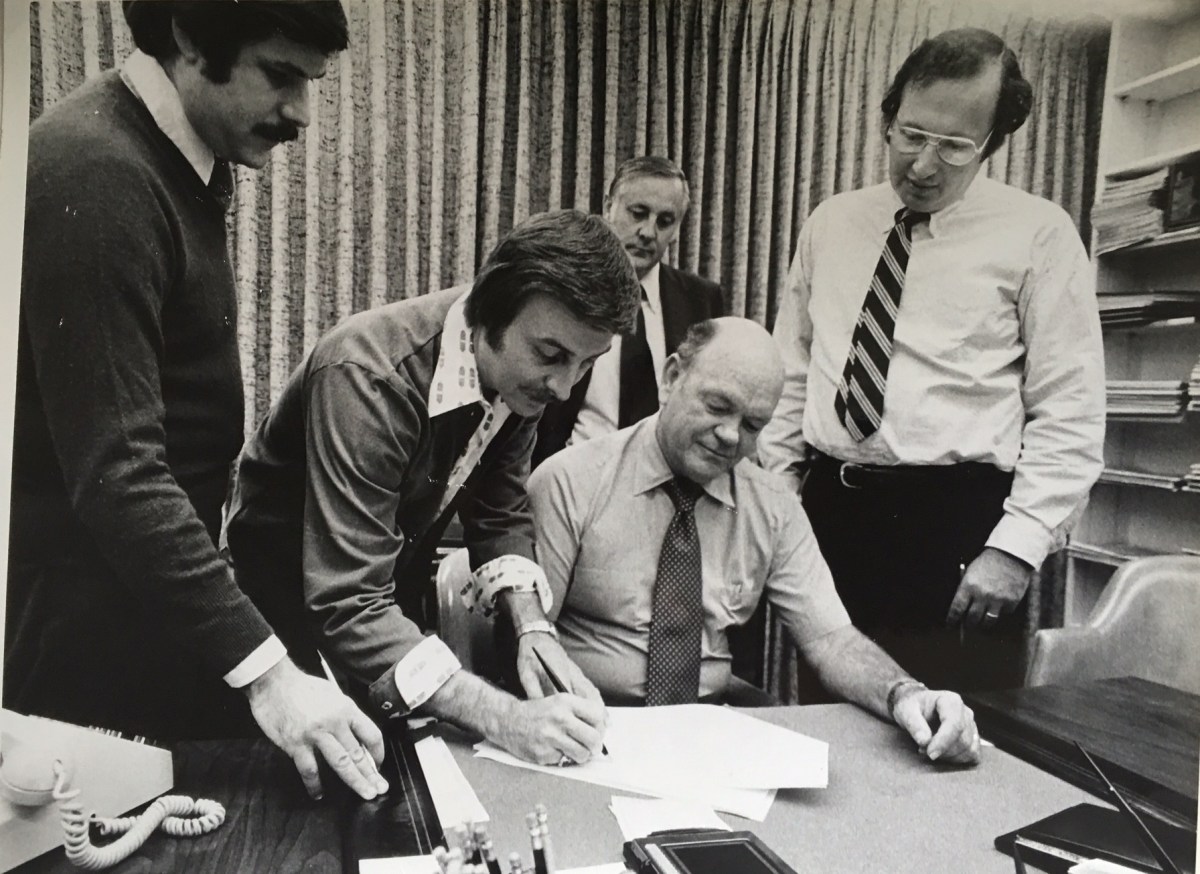

Along the way, Hershey went from learning how to arm and throw a live grenade at basic training at Fort Gordon in Georgia—he came close to blowing up his sergeant—to organizing journalists at Newsday to join a union with the pressmen and the drivers. As Hershey wryly observed, “Start a union and you aren’t exactly a favored staffer.”

Management had not been keen on the idea, telling reporters and editors that they had nothing in common with the blue-collar members of Local 406. But then the pressmen and drivers were making a lot more than the ink-stained wretches, as their pay stubs clearly showed.

“The difference between these employees and us is that they have a union,” Hershey explained to those willing to listen. Despite the disparity in pay, the vote for joining the union came down to the wire: 149-144. In the end the union won. Hershey still counts it as one of his life’s crowning achievements. He also serves on the George Polk Awards committee, which honors the best and brightest in journalism today.

The Scorekeeper is not a score settler, although Hershey tells it like it is. It’s also very entertaining. Here’s a guy who could say with a straight face that he’s been a basketball announcer, an antiques columnist and a labor union strategist.

He’s also worked on the other side, as reporters call it when you trade a byline for a public relations gig, when he became a communications director for the city’s corrections commissioner, Long Island University (his alma mater) and Colby College in Maine. Being a flack was a revealing experience.

“All those years writing stories I thought mattered and hardly anyone knew my name,” he told his wife after one appearance. “Now I stammer a sentence or two on TV and I’m a celebrity.”

Hershey would be the first to admit today he’s no celebrity, but the stories he tells in The Scorekeeper make him a winner for those who value the contributions made by the Fourth Estate as they try to speak truth to power.

Hershey will be at the Book Revue in Huntington at 7 p.m. on Thursday, Jan.26, reading from his book, The Scorekeeper: Reflecting on Big Games and Big Storeis, Brooklyn Roots and Jewish-American culture, the Craft of Reporting and Art of The Spin, and signing copies.

In the photo, Hershey, on the left, watches his union president George Tedeschi sign the contract that joined reporters and editors with pressmen and drivers in Local 406, as Newsday editor in chief, and later publisher, Dave Laventhol, observes on the right.