Joining a chorus of criticism from privacy advocates and ethics experts, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer called on President Donald Trump Sunday to veto a controversial bill passed by Congress allowing Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to sell customer data to advertisers without their consent.

“Signing this rollback into law would mean private data from our laptops, iPads and even our cellphones would be fair game for internet companies to sell and make a fast buck,” said Schumer. “An overwhelming majority of Americans believe that their private information should be just that—private—and not for sale without their knowledge. That’s why I’m publicly urging President Trump to veto this resolution.”

The bill passed in the House of Representatives last week 215 to 205, despite Democrats opposing the measure and 15 Republicans voting “no.” It narrowly passed the U.S. Senate a week earlier. Republicans argued that the bill would put ISPs on fairer ground with Internet giants like Facebook and Netflix, two companies that already gather vast amount of personal data. The difference between those social media networks and entertainment companies and ISPs, however, is that internet providers can see everything a user does online, while Netflix is monitoring behavior within its ecosystem.

The measure effectively prevents the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) from adopting rules it previously put in place last October restricting ISPs from profiting off their customers’ search history. If President Trump signs the bill into law, as expected, internet providers such as Optimum or Verizon FIOS on Long Island would be able to sell customer data—search history, what online stores you visit, etc.—to marketing companies.

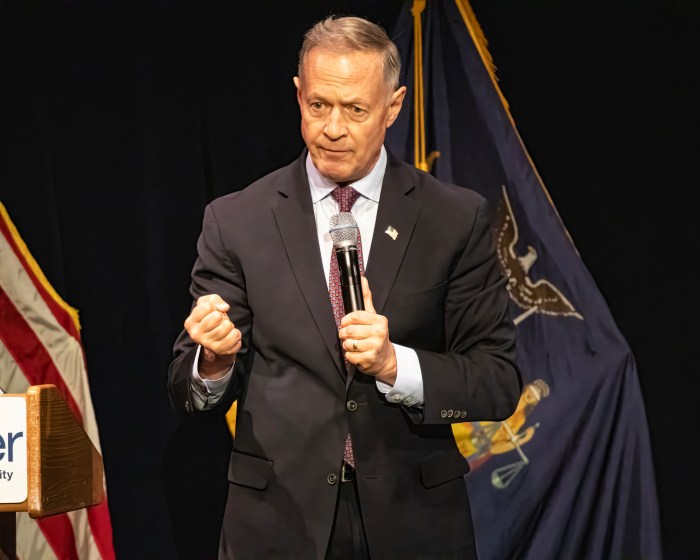

“What’s going to happen is you’re going to see more and more targeted ads when you surf online,” said Mark Grabowski, internet law and ethics professor at Adelphi University. “So, for example, if your kid’s teacher emails you that he’s struggling in Algebra, you might see ads about tutoring services. If you do a Google search for flights to Paris, expect to see ads from airlines and hotel websites. You get the idea.”

Grabowski noted that “someone can’t buy your specific internet history,” and that companies purchasing your history won’t know your identity.

“There’s lots of misinformation about this—although it’s still bad news,” Grabowski added. “In short, nothing is changing. You didn’t have online privacy to begin with, so you’re not losing anything.”

When asked specific questions regarding whether it currently shares consumer data with advertisers and the bill’s ramifications on the company’s current privacy policy, Altice USA, which owns Cablevision, passed along a statement from The Internet & Television Association cheering the bill’s passage.

Steps taken by Congress to “repeal the FCC’s misguided rules marks an important step toward restoring consumer privacy protections that apply consistently to all internet companies,” the statement read. “With a proven record of safeguarding consumer privacy, internet providers will continue to work on innovative new products that follow ‘privacy-by-design’ principles and honor the FTC [Federal Trade Commission]’s successful consumer protection framework. We look forward to working with policymakers to restore consistency and balance to online privacy protections.”

Verizon did not respond to a request for comment.

Privacy advocates vehemently objected to the proposed law.

“Should President Donald Trump sign S.J. Res. 34 into law, big internet providers will be given new powers to harvest your personal information in extraordinarily creepy ways,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, a privacy advocacy group, said. “They will watch your every action online and create highly personalized and sensitive profiles for the highest bidder. All without your consent. This breaks with the decades long legal tradition that your communications provider is never allowed to monetize your personal information without asking for your permission first.”

Anyone with possession of an internet user’s search history can glean vasts amounts of insight into that person: potential health problems, political leaning, sexual orientation, purchase habits and more. Marketers can then place advertisements on webpages based on a user’s search history.

“Reversing those protections is a dream for cable and telephone companies, which want to capitalize on the value of such personal information,” Tom Wheeler, former FCC chairman under the Obama administration, wrote in The New York Times. “I understand that network executives want to produce the highest return for shareholders by selling consumers’ information. The problem is they are selling something that doesn’t belong to them.

“Here’s one perverse result of this action,” he continued. “When you make a voice call on your smartphone, the information is protected: Your phone company can’t sell the fact that you are calling car dealerships to others who want to sell you a car. But if the same device and the same network are used to contact car dealers through the internet, that information—the same information, in fact—can be captured and sold by the network. To add insult to injury, you pay the network a monthly fee for the privilege of having your information sold to the highest bidder.”

Consumers have become savvier in recent years to protect their personal information by turning to encrypted messaging services and Virtual Private Networks (VPN), the latter of which can disguise where a person is using the internet. One company offering such protections, NordVPN, said it saw an 86-percent surge in inquiries in the first few days after Congress passed the law.

Experts in internet privacy acknowledged that consumers had little privacy even prior to Congress passing the bill. The FCC rule the bill repealed had not even gone into effect, and companies have long been gathering consumer data, but previously required permission before putting it for sale.

“Deregulation of internet service providers has been a disaster for Americans,” Adelphi’s Grabowski said. “ISPs haven’t delivered the promises they made when they begged Congress to end common carriage regulations in the ’90s. Twenty years later, we’ve gone from being a pioneer in internet service to now lagging behind developing countries in terms of access, cost, speed, privacy protections and more. And this situation will probably continue to get worse.”