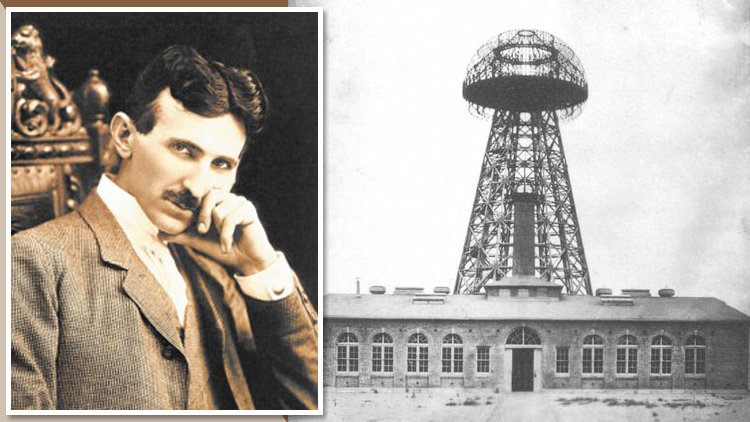

On Independence Day, 100 years ago this summer, scrap dealers dynamited Nikola Tesla’s 187-foot Wardenclyffe Tower in Shoreham, marking the final chapter of the Serbian-born scientist’s doomed dream to “send the human voice and likeness around the globe through the instrumentality of the earth.”

Today, still standing nearby – remarkably – is Tesla’s red-bricked laboratory, designed in 1901 by famed architect Stanford White and built with money from J.P. Morgan, the Wall Street tycoon.

What’s left is in shambles and infested with mold, but a statue of Tesla, a beacon for the future as some call it, has been erected near where the tower once stood, a gift of the Serbian Republic in 2013.

If all goes well over the next few years, the non-profit Tesla Science Center at Wardenclyffe will open to the public with a visitors’ center, an office, classrooms, and an exhibit space to keep his spirit alive for generations to come.

“We want to get it back to its original glory,” said Jane Alcorn, president of the Tesla Science Center. “It can be a source of inspiration for people who want to follow in Tesla’s footsteps.”

Towering ambition

Tesla inventions include AC current, robotics, fluorescent lighting and the bladeless turbine, and yet he died penniless at the New Yorker Hotel in 1943. Most Americans know him today only because his last name is on the high-end electric cars championed by Silicon Valley billionaire Elon Musk. Those innovative vehicles, which run as much as $100,000, wouldn’t go anywhere without a version of Tesla’s induction motor operating inside them.

Back at the beginning of the 20th century, Tesla envisioned a huge communications complex on his 200-acre property that he had named Wardenclyffe after James S. Warden, director of the Suffolk County Land Co., who had handled the real estate deal.

Since 1897, Tesla had been living in style at the Waldorf-Astoria, thanks to his friendship with John Jacob Astor. The inventor would routinely take the Long Island Rail Road out to Shoreham Station to watch his lab take shape, sometimes asking an assistant to commute from the city with a specially prepared picnic lunch.

Tesla had big plans for Wardenclyffe as a transmission center of just about everything, including “press messages, stock quotations, pictures for the press and these reproductions of signatures, checks and everything transmitted from there throughout the world.”

The inventor also planned “to give a demonstration in the transmission of power which I have so perfected that power can be transmitted clear across the globe with a loss of not more than 5 percent.”

Among the many devices and pieces of equipment the lab building contained were two 300-horsepower boilers, pumps, injectors, two galvanized steel water tanks capable of holding 16,000 gallons, and a 400-horsepower Westinghouse reciprocating engine, “driving a directly connected dynamo which was specially made for my purposes,” Tesla later explained. He also had special transformers designed “to stand an electric tension of 60,000 volts.”

But the most important structure was the tower. At the top was a 55-ton steel globe to store electricity, beneath which was a shaft, 10 feet by 12 feet wide, lined with steel and supported by timbers, with a winding staircase running 120 feet into the ground. At the bottom, 16 steel rods plunged hundreds of feet deeper.

“In this system that I have invented,” Tesla explained, “it is necessary for the machine to get a grip of the earth. Otherwise it cannot shake the earth. It has to have a grip on the earth so that the whole of this globe can quiver.”

What Tesla did not have a good grip on was the investment community, including his trusty benefactor J.P. Morgan.

Almost two years before, Guglielmo Marconi had managed to send a simple Morse code transmission from England to Newfoundland using 17 of Tesla’s patents, and that was enough to persuade Morgan to invest in the cheaper, proven technology of radio.

Tesla countered that his Wardenclyffe Tower – together with a half dozen matching complexes erected elsewhere around the globe – would be able to send energy, wirelessly, wherever it was needed.

As Morgan reportedly replied, “Free power to the whole world? But where do we put the meter?”

Marconi’s simple radio transmission based on Tesla’s patents was financially successful “because he was willing to incrementally accomplish something,” said Marc Alessi, an entrepreneur and attorney who has played a crucial part in helping preserve Wardenclyffe.

“When J.P. Morgan questioned why Marconi had beat him, Tesla was like, ‘Well, he’s only doing a single transmission! I’m doing multiple band-width radio with channels!’

“Which is what we use today. Tesla didn’t care about financial success or business. He wanted to move the dial for humanity.”

And it cost him.

Making America glow

Tesla had established the principles for modern electric power even before he left Europe for New York in 1884, perfecting alternating current, or AC, as opposed to the DC current inventor Thomas Edison was banking on.

In 1887, Tesla filed seven U.S. patents for AC motors and power transmission, which caught the attention of Pittsburgh industrialist George Westinghouse, who tracked Tesla down in Manhattan and bought the rights to it all for $60,000. Included: 150 shares of Westinghouse Corp. and royalty payments of $2.50 per every horsepower of electrical capacity sold.

Backed by Westinghouse, Tesla illuminated the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, out-dazzling Edison at the Electricity Pavilion and inspiring Frank Baum to conjure the Emerald City in his book, “The Wizard of Oz.”

Tesla’s triumph in the Windy City helped Westinghouse win the contract to build the Niagara Falls Power Project, which lit up Buffalo for the first time on Nov. 16, 1896.

AC had won the electrical race, but the battle had been costly. Forced to pay lucrative royalties to Tesla, Westinghouse was nearing bankruptcy, and J.P Morgan was close to taking over the company.

But Tesla saved the day.

“He ripped up his royalty contract with Westinghouse for alternating current, and the whole reason was that he wanted to make sure that people had electricity,” said Alessi.

A noble deed, but one that led, ultimately, to Tesla’s own financial ruin. Lacking funds, he was forced to shut down his beloved Wardenclyffe in 1906 and, worse, deed the property to Waldorf-Astoria manager George C. Boldt to settle his hotel bill of $20,000, a bit more than $500,000 today.

Astor, his friend and last financial hope, went down with the Titanic in 1912. Westinghouse died in 1914.

That July 4 demolition was Boldt’s attempt to recover his $20,000, selling Wardenclyffe for scrap. The rubble, however, brought a meager $1,750.

Tesla was philosophical: “My project was retarded by the laws of nature,” he wrote. “The world was not prepared for it. It was too far ahead of time, but the same laws will prevail in the end and make it a triumphal success.”

Success might have been more clearly triumphal had he bothered to commit the fundamentals of wireless energy to paper.

Though thoroughly defeated professionally, Tesla remained a tantalizing public figure, even making the cover of Time magazine in 1931, when he turned 75. (Einstein wrote him a birthday greeting, congratulating Tesla on “the magnificent success of your life’s work.” Tesla, interestingly, had scoffed at Einstein’s theory of relativity and said that “the idea of atomic energy is illusionary.”)

In 1934, Tesla was written up in The New York Times, this time over news of his latest invention, “a peace ray,” that could send concentrated beams of particles through air, “of such tremendous energy that they will bring down a fleet of 100,000 enemy airplanes.”

(Additional research: See the Reagan-era Star Wars initiative.)

By then the Westinghouse Corp. had quietly arranged to put Tesla up in a pair of rooms at the New Yorker, where he lived for his final decade, leaving only for walks and to feed pigeons in a nearby park. Though once a regular at Delmonico’s, Tesla became a vegetarian in later life, subsisting on vegetables, bread and honey.

He died on Jan. 7, 1943 after putting out the “Do Not Disturb” sign, ignored in the morning by a maid. The coroner ruled the death the result of coronary thrombosis. He was 86.

FBI agents rushed into Tesla suite soon after his passing to impound his papers and keep sensitive materials – the peace ray! – out of enemy hands.

Here’s an unexpected twist: Among the Americans called in to analyze Tesla’s papers was Dr. John G. Trump, uncle of the current president, who was an electrical engineer with the National Defense Research Committee of the Office of Scientific Research and Development.

After a three-day investigation, Trump concluded there was nothing of significance among the Tesla papers, although he later admitted he hadn’t bothered to look at everything gathered. Ultimately, all of Tesla’s surviving material – that the government admitted to, conspiracy theorists remind us – was packed off to the Tesla Museum in Belgrade.

Saving the lab

In 2010, Wardenclyffe was in danger of being bulldozed and redeveloped. The Agfa Corp., which acquired the property from Peerless Photo Products in 1969, had spent more than $5 million cleaning up heavy metal contamination at the site, and the state had given a final OK for sale. Agfa’s asking price was $1.65 million.

Wardenclyffe was about to be sold to a housing developer when Babylon-based film director Joseph Sikorski used $33,000 he’d raised for a movie on Tesla to establish a last-ditch, save-the-lab effort, while his partner, Vic Elefante, did a separate documentary, “Tower to the People,” that shed more light on Tesla’s Long Island connection.

“People are more familiar with the car than with Tesla,” Sikorski said. “I’m trying to rehabilitate his image so people might take a second look.” He decried the TV shows and websites that make Tesla look “like a kook and a mad scientist.”

“By discrediting him like that, we make it harder for serious scientists to look at his work and continue his research.”

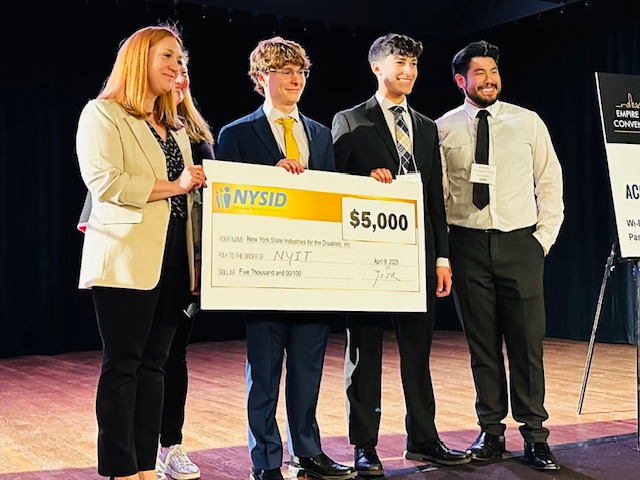

In 2012, Matt Inman, the comic creator of The Oatmeal, who said he’d fallen in love with Tesla because he was “a geek,” set up an Indiegogo.com crowd-funding site to raise money for what he called, “Operation Let’s Build a Goddamn Tesla Museum.” It raised nearly $1.4 million in 45 days.

According to Alcorn, donations came from more than 30,000 people around the world, followed by a $1 million pledge from Musk’s personal foundation.

(It’s a good start, but just that: According to Alessi, who’s on the science center’s board, rebuilding Wardenclyffe could run more than $17 million.)

“Tesla is someone we call, nowadays, a disruptive person,” said Alcorn, likening him to Bill Gates, Steve Jobs and Musk. “What they do disrupts the normal pace of things and takes us in giant leaps.”

“He was definitely a futurist,” she added. “In 1926, Tesla was talking about how someday people would be carrying a device with which they would be able to transmit images, words, actual voices and texts and so on, and carry it in their vest pocket.

“And what are we carrying around today?”

Atop the pedestal on which the sculpture of Tesla stands facing his former laboratory in Shoreham, is engraved a quotation of his that runs in English on one side and Serbian on the other. It reads, in part: “Were I to have the good fortune to implement at least some of my ideas, it would be for the benefit of the entire humankind.”

That’s Tesla. Never a small thinker.