Mary Mallon had spent most of her life living in squalid housing in the Lower East Side, but on August 4, 1906, she was escaping from all that, seated in a Long Island Rail Road car bound for Oyster Bay. The train pulled into the elegant new station that featured oyster shells in the exterior cement. She was looking forward to clean, cool, bay breezes.

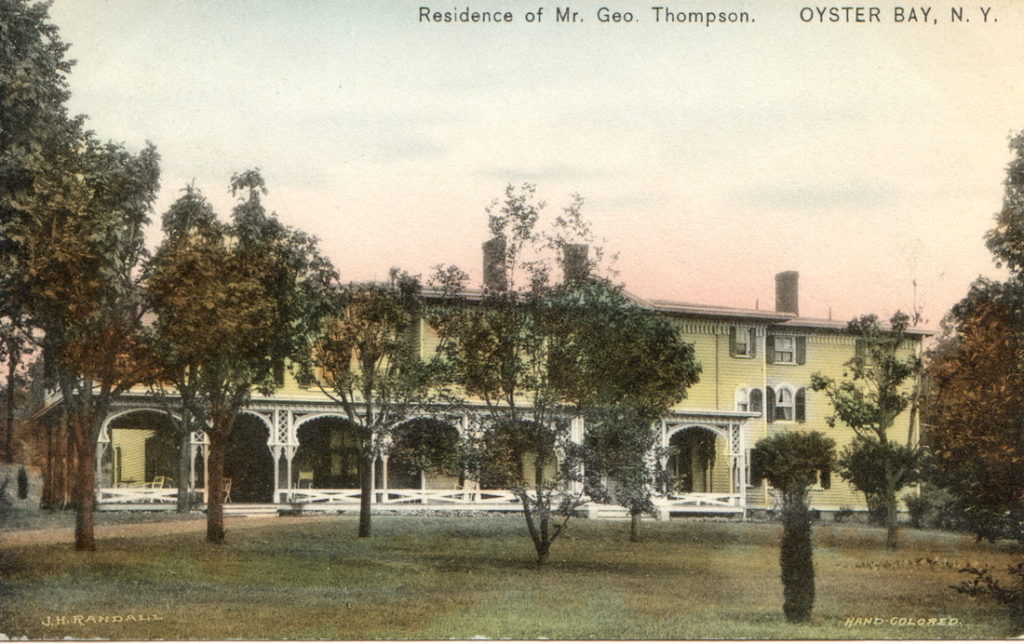

She had been hired as a cook by Charles Henry Warren, the president of Lincoln Bank in Manhattan and banker to the Vanderbilts. Warren had rented a large yellow house with a wraparound porch at the corner of McCouns Lane and East Main Street. The mansion had well-manicured grounds at the edge of town sloping down to the bay, near President Theodore Roosevelt’s summer White House.

Mallon had come far since landing on American soil in 1883 as a 15-year-old from Ireland. The only people she knew were her aunt and uncle in New York City. They took her in but died shortly after. Mallon—also known as Mary Malone—had to fend for herself, a teenager with no family or friends, forging her way in a foreign land that was not entirely welcoming.

Earlier in the century in the mid-1800s, Americans had accused Irish immigrants of being rapists, carrying disease, practicing an un-American religion, and taking jobs away from American citizens—not unlike the anti-immigrant arguments of today. But by the late 19th century, those suspicions had lessened. Like many other immigrants, Mallon found work as a trusted domestic. She was a tall, blond, hard-working young woman who craved independence. She learned about cooking and became known as a good, plain cook, working for well-to-do Manhattan families. By 1900, the 37-year-old was preparing meals for prominent families, earning $45 per month, considered good wages. But she kept to herself and was seen as unsociable by the other servants.

Her specialty was dessert, so one night she made home-churned ice cream with fresh-cut peaches for the Warren household. Just weeks later, more than half the people served came down with typhoid fever. Between August 27 and September 3, six people fell ill. Three weeks after the outbreak, Mallon left abruptly, giving no notice.

Distrust and Denial

Typhoid attacked its victims with high fevers, aching muscles, stomach pains, exhaustion, and constipation or diarrhea. Untreated, the highly contagious infection could kill one in five people; in 1900, it killed 35,000 Americans. There was no cure, antibiotics didn’t exist, and a vaccine was not yet available.

Medical practitioners supported the “filth theory” of contagion, which held that typhoid was spread by unsanitary surroundings and people with poor hygiene and toilet habits. Immigrants, assumed to live in disease-ridden crowded housing, became scapegoats.

But what about the upper-class Warrens? None of them had associated with infected people.

Previously, medical disease theory of the 1850s embraced the “miasma theory,” blaming vapors (foul air) and environmental causes such as contaminated water and poor hygiene. In the late 1800s, doctors found that the typhoid toxin was transmitted through excrement and that water contaminated by human feces was responsible.

In 1900, researchers proved the germ theory: Tiny organisms invisible to the naked eye—like the typhoid-causing Salmonella typhi—could inhabit people and cause disease. This discovery revolutionized medicine.

But people remained suspicious of the invisibility theory. They couldn’t believe that things that couldn’t be seen could sicken humans—even in the best of homes.

When The New York Times covered the Oyster Bay outbreak, the home’s owner George Thompson panicked. As a member of the Seawanhaka Corinthian Yacht Club at Oyster Bay, he had to protect his reputation. Fearing the home would be condemned and burned down by the health department, in the winter of 1906, Thompson hired epidemic expert Dr. George A. Soper.

The New York City Health Department sanitation engineer at first blamed soft clams for the outbreak. But after nearly a year, Dr. Soper switched theories. He had learned that Mallon had started working in Oyster Bay on August 4—about three weeks before the outbreak. Dr. Soper was the first to suggest the “healthy carrier” theory of an asymptomatic person—one who is healthy but transmits disease.

Physicians of that era discovered many facts about disease, but much was still unknown. Also unknown was that Mallon had survived a mild case of typhoid fever as a child.

Give Me Your Urine

In 1907, 3,000 New Yorkers had Salmonella typhi. Dr. Soper found that during the previous 10 years, seven of the eight households Mallon worked in had come down with typhoid cases; 22 people were infected, and several died. In 1904, when she was the cook at Henry Gilsey’s Sands Point summer estate, four servants became infected. People would become ill within weeks of her arrival, and she would vanish soon after.

Dr. Soper suspected that Mallon’s body was a typhoid breeding ground. We now know that 5 percent of infected people become chronic carriers, excreting typhoid bacteria in their feces for a year or more. Doctors posited that Mallon didn’t wash her hands thoroughly so she transmitted germs when handling food—as when cutting up raw peaches for ice cream desserts.

Dr. Soper had to test specimens to prove his theory. While investigating an outbreak at a Park Avenue brownstone in March 1907, he met the cook: It was Mallon. He recalled in 1939, “I told her she was spreading death and disease through her cooking.” With a less-than-compassionate bedside manner, he insisted on taking samples of feces, urine, and blood for tests. Her reaction? “She seized a carving fork and advanced in my direction.” He quickly fled.

But he continued to zealously stalk Mallon where she worked and at her home. The health department, backed up by police, apprehended Mallon in 1907 after chasing her for hours, and forced her to give samples. Her stool tested positive for typhoid.

Up the River

With no trial, against her will, Mallon was physically restrained and taken to North Brother Island near Rikers Island. She was placed in involuntary confinement in a bungalow.

During the typhoid epidemic, people panicked, distrustful of each other and the authorities, and carriers were attacked by mobs. As Anthony Bourdain writes in Typhoid Mary, “It was not unheard of for those thought to be infected to be run out of town on a rail or set adrift in the Long Island Sound.”

During two years in confinement, most of her stool samples tested positive for typhoid. But no one tried to explain to Mallon why being a carrier was dangerous. After being hounded by Dr. Soper, she complained that the City of New York was persecuting her, insisting she had done no wrong. In 1908, the Journal of the American Medical Association dubbed her “Typhoid Mary.” Public sentiment was against her: She was a single, headstrong Irishwoman with no family or children, said to be the source of hundreds of typhoid infections.

A new health commissioner freed her in 1910. She promised to work as a domestic and not cook. But the department never trained her for a job that would pay well. Her laundress’ pay was inadequate so she resumed cooking, under assumed names. She fled her position at Sloane Maternity in Manhattan after 25 people fell ill—and two died—in three months. While working as a cook on a Long Island estate in 1915, she was apprehended, and again confined.

She protested by writing letters, saying she had “always been healthy,” and asking, “Why should I be banished like a leper and compelled to live in solitary confinement?” Doctors tried convincing her that while she seemed healthy, she spread bacteria. She didn’t believe them. They told her to wash her hands more often, more carefully. She didn’t listen.

Dr. Soper had described Mallon’s violent temper. Others said she had trouble making or keeping friends. She was seen as extremely determined and painfully isolated, even before being pursued.

But what if her suspicions (especially after being captured) resulted from her childhood typhoid? The Mayo Clinic states, “Untreated typhoid can cause permanent psychiatric problems such as delirium, hallucinations, and paranoia over the long term,” defining paranoia as “a symptom of a psychotic disorder in which patients become suspicious of others and feel that the world is out to get them.”

After 26 years of captivity, Mallon died in 1938. Historians say she contaminated at least 122 people and killed five. That same year, some 400 healthy carriers were identified and observed by the health department—but they were not confined. Mallon had broken no laws, but was exiled. Some say she was judged for being an Irish immigrant, for not staying out of the kitchen, and for being a noncompliant single woman.

After Mallon’s death, Dr. Soper wrote, “There was no autopsy.” Others reported that an autopsy was performed and showed that she shed Salmonella typhi bacteria from her gallstones. The National Institutes of Medicine calls the latter “another urban legend, whispered by the Health Center of Oyster Bay, in order to calm ethical reactions.”