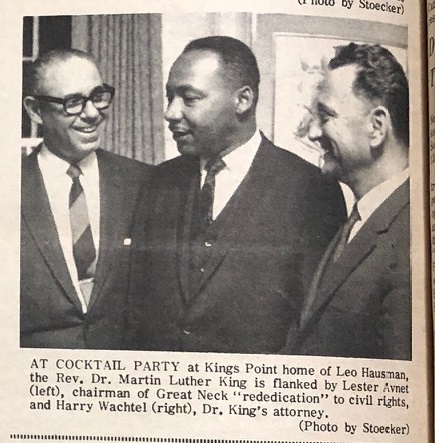

For many, summer celebrations would be nothing without hearing John Philip Sousa’s The Stars and Stripes Forever. The 1896 march conveys images of flags waving, parades, and the sense that everything will be alright.

Bringing music to the masses, evoking nostalgia for a simpler time, the “Pied Piper of Patriotism” and self-proclaimed “salesman of Americanism” was so popular that a Liberty battleship, a Washington, D.C. bridge, and schools — including John Philip Sousa Elementary in Port Washington — bear his name.

TALENT AND TIMING

His childhood was as American as can be. He was born in Washington, D.C., next to the United States Marine Barracks, the first son of European immigrants. His father played trombone in the U.S. Marine Band.

By 1861, the lad with perfect pitch was an award-winning multi-instrumentalist at a private conservatory. He studied harmony, composition, and violin as the sounds of military bands and Civil War battles echoed nearby.

When he was 13, a traveling circus offered him a bandleader position. He later wrote that he wanted “to follow the life of the circus, make money, and become the leader of a circus band myself.”

He tried running away but his father enrolled him as a Marine Band apprentice. At age 19, he published his first march. He became a solo violinist, conducted Broadway and vaudeville orchestras, and wrote operettas. Appointed the Marine Band’s leader, in 1888 he composed Semper Fidelis, which became the Corps’ official march.

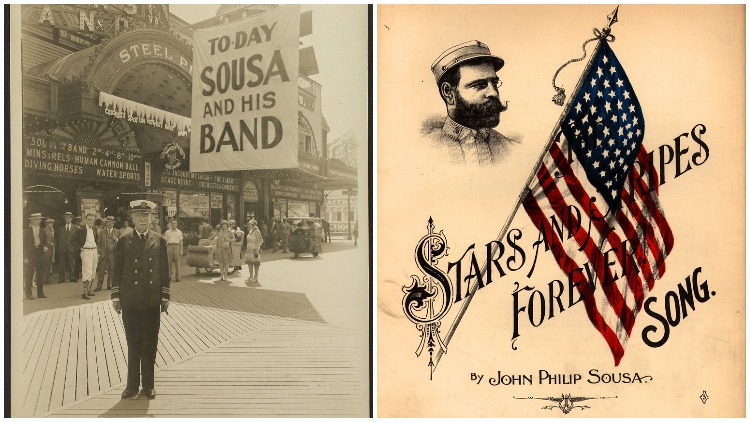

He moved to Manhattan in 1892 and formed his own symphonic concert band. Neil Harris’ Library of Congress biography described how the “carefully groomed Sousa, clad in tight fitting uniform and spotless white gloves, acted out the maestro.”

Sousa mastered marketing his brand as public relations wizards worked the press. He had an instrument created, the Sousaphone. The newly invented phonograph had recorded the Marine Band marches, making the the world’s first recording stars. Among those marches was his famous 1896 Stars and Stripes Forever.

MORE THAN MARCHES

In the late 1800s, agricultural America was becoming an industrial powerhouse; German, Scandinavian, and other immigrants fled to America; the nation struggled for global domination after warring with Spain over Cuba in 1898.

Sousa faced criticism. Frederic D. Schwartz wrote in American Heritage that critics at the time remarked on The Stars and Stripes Forever’s “‘jingoistic’ or ‘martial’ character.”

In Lawyers, Guns, & Money, University of Rhode Island Professor Erik Loomis calls Sousa “the composer and conductor of America’s soundtrack for imperialism and colonization.”

During the Victorian era, many held that America was culturally inferior to Europe, an attitude that irritated Sousa. But on their first European tour in 1900, his musicians impressed audiences, mastering dynamics to include different levels, unlike other bands’ often bombastic sounds. The dapper mustachioed showman, a mason and member of the Sons of the Revolution, attracted a following by offering humor, perfection, and patriotism.

BAND PLAYED ON

In 1914 America joined World War I and Sousa, 62, enlisted in the Naval Reserve. His navy band was so popular that it raised $21 million for the war effort. As Howard Reich wrote in

the Chicago Tribune, “… And out of that noisy, cacophonist din came the measured, four square, reassuring beat of the ‘Sousa March.’”

In 1915, Sousa moved to Wild Bank at 14 Hicks Lane in Sands Point. His band continued performing, including 1923 and 1924 concerts at Ward & Glynne’s movie palace (today’s Patchogue Theatre), and he advocated for children’s music education and composers’ rights.

In 1932, he rehearsed The Stars and Stripes Forever with the Ringgold Band for a Philadelphia concert. The next day he died of heart disease at the Abraham Lincoln Hotel. Wild Bank is now a National Historic Land- mark; in 1987, Congress named his Stars and Stripes the National March.

Ironically, although “The March King” wrote more than 100 marches, his band marched in just eight parades.