Massapequa Water District holds informational meeting

A series of slides flashed on the screen, showing the spread of the toxic plume over the decades. One could not help likening it to the growth of a cancerous tumor.

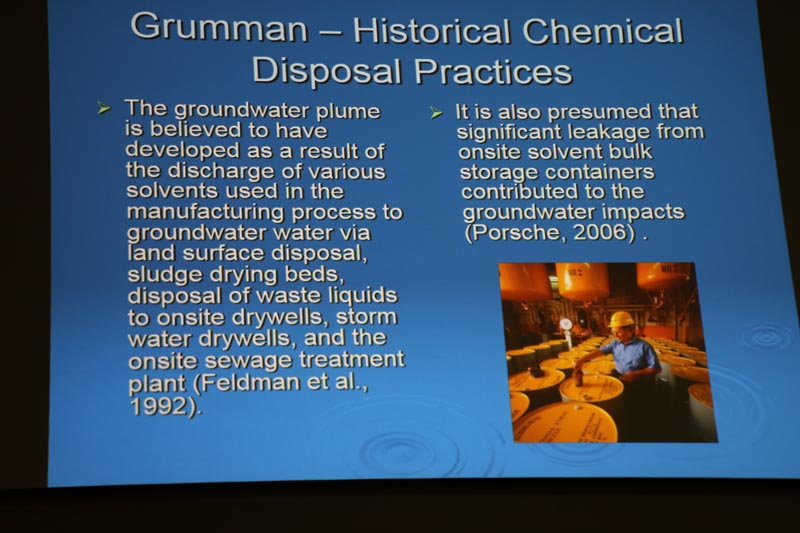

Massapequa Water District (MWD) Superintendent Stan Carey summed up the response taken by the responsible parties ever since groundwater contamination was discovered at the Grumman and Navy manufacturing facilities in Bethpage in the 1970s.

“For 35 years, the approach has been extremely slow, non-responsive, not effectively managed from a global approach, [with ] no accountability,” Carey read off a presentation slide projected on a screen at the Massapequa High School auditorium. “And the plume has traveled over two miles and doubled in size.”

MWD officials had called the public meeting on July 26 to discuss the Navy-Grumman Plume, the toxic stew that is contaminating Long Island’s sole drinking water aquifer and became subject to investigation in the 1980s and remediation in recent decades.

Another slide declared that the plume represented “a history of slow action and failure to protect public water supply wells.”

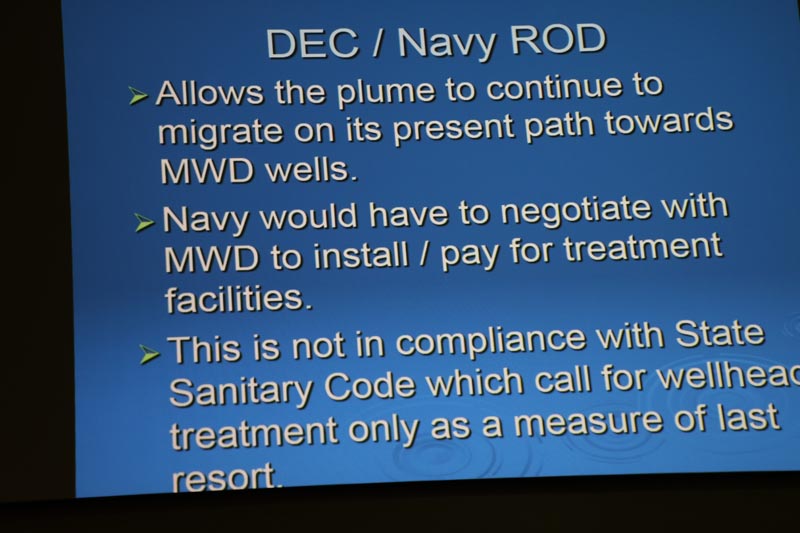

“Allowing groundwater contamination to remain and not be subject to cleanup is not in compliance with [New York State] law,” Carey declared. “Wellhead treatment should only be considered as a measure of last resort. I keep saying it, because the DEC hates it every time I bring it up.”

When Will It Reach The Wells?

The most important questions revolved around when the plume would be remediated, and when the contamination would reach the MWD wells.

As far as the latter question, Carey remarked, “Depending on the speed of the plume (estimated at 1-2 feet per day), which is influenced by several factors…we don’t know. It could be three years. It could be 10 years.”

He added, “The fact that there is time [means] that we could do something now to intercept the plume and protect our drinking supply here in Massapequa. We’ve been advocating for a long time to intercept the plume hydraulically.”

The MWD has nine drinking water wells downgradient of the plume, and the Navy has installed several early warning wells upgradient of the supply wells. These monitoring wells are tested quarterly and so far have not been impacted by the plume’s main contaminant, trichloroethylene (TCE). Heavily used as a metal degreaser in manufacturing operations at Grumman, it has been classed as a potential carcinogen and the drinking water standard is five parts per billion (PPB).

The record of decision (ROD) agreed to between the Navy and the state Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) commits to Navy to treat only what are called “hot spots,” areas in which the TCE concentrations have reached 1,000 or more ppb.

Carey made it clear that the MWD and fellow water district leaders have strongly disagreed with this ROD and have sought to change it over the years. He noted that it leaves a whole range of potentially harmful non-hot spots untreated.

One slide noted that the ROD “allows the plume to migrate on its present path toward MWD wells.”

The monitoring wells, once contaminant levels are found there above the drinking water standards, will give the district three to five years to design a treatment system, put out bids and build it before the contamination reaches the supply wells.

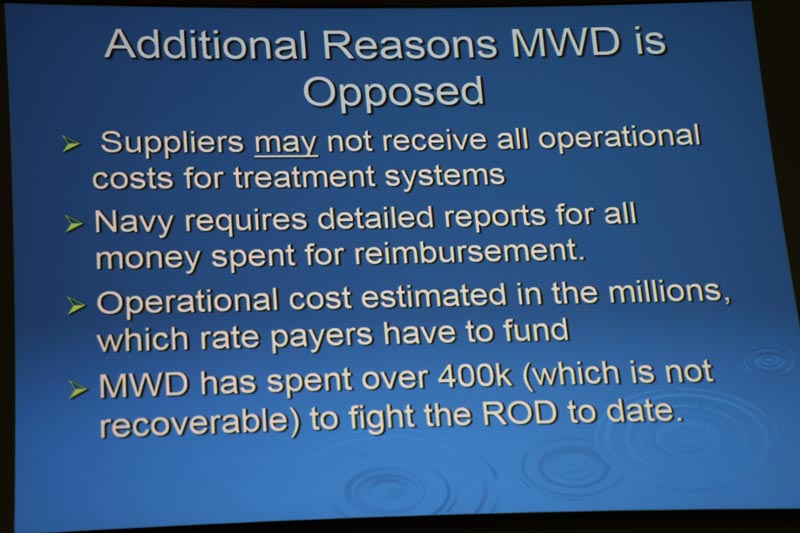

As with what happened in South Farmingdale next door, the Navy would pay for the treatment systems. But to Carey, this is not an ideal solution as it would involve complicated negotiations with the Navy. As South Farmingdale found out, the Navy might not pay for all the operational costs following the completion of the treatment system, and will require detailed expenditure reports to reimburse the district.

The operational costs, according to Carey, would rise to the millions, which ratepayers will have to fund.

The ‘Big Shift’

Carey related the countless letters written to and meetings with elected officials the MWD engaged in, and a petition with more than 5,000 signatures delivered to the governor’s office after the attempt to fax the signatures jammed the governor’s fax machine. All of this activity seemed to produce little response.

But what he called “a big shift” happened in 2014, when Governor Andrew Cuomo signed a bill sponsored by then Assemblyman Joseph Saladino (now Oyster Bay supervisor) calling on the DEC to study the feasibility of hydraulically containing the plume. The study was completed in 2016 and last December, Governor Cuomo traveled to Long Island to announce that the state will commit $150 million to contain the plume.

“That was great news for us,” observed Carey. “And he said all the things that Massapequa and the other water districts were saying all these years.”

The governor also had strong words for the Navy and Grumman, saying that the state would sue to recover its cleanup costs.

“We can’t let the plume continue. We have to prevent impacts to other public supply wells. And we certainly can’t let it get to the Great South Bay—these were the governor’s words, so it was great news,” Carey observed.

Carey believed what happened with the drinking water supply in Flint, Michigan—where an unelected city manager shifted the source to what turned out to the contaminated Flint River—caused public officials to become more alert to policy.

“The elected officials actually got charged in Flint because they did not follow the proper protocols…and people got indicted,” Carey said. “We think this really woke people up at the state level, and that’s why there was a big shift in the state’s position.”

Wells Galore

The plan envisioned by the state would be to install recovery or capture wells at the leading edge of the plume to pump out contaminated water. Then pipe the water to treatment systems (using both the state-owned Bethpage Parkway and Seaford Oyster Bay Expressway as right of ways), clean the contaminated water up to drinking water standards, and then pump it back into the aquifer.

The DEC has already placed some wells in preparation for its operation, but is still in its remedial investigation phase. Sometime this fall, it will hold a proposed remedial action plan (PRAP) meeting. It is here that the water districts already affected (Bethpage) and potentially affected (Massapequa, South Farmingdale) hope that the public will show up to put pressure on public officials.

“Either write a letter and get it placed in the record—or better yet, show up,” Carey encouraged. “Just get up and say two sentences: ‘This should have been cleaned up years ago. Clean up our drinking water. Do not allow it to continue to Massapequa.’ If you say that little, it’s a big help. That’s what they listen to—the public. Demand that your drinking water is protected for future generations.”

Carey added, “The biggest takeaway tonight is the shift in the state’s position. They’re going to call for total plume containment.”

Radiologic Concerns

During the question phase, Carey was asked about the high radium levels found last year at two schools in the Bethpage School District. Was it possible that the radioactivity was approaching BWD?

“The answer to that is no,” Carey replied. “We are required to do radiological testing every three years in Massapequa—and the [numbers] are within normal limits. Some of the radium that was found in those areas can be considered naturally occurring. And I know that’s being challenged because of the [high] concentrations. We don’t suspect anything coming from the north. Radiological material really doesn’t travel like the other plume chemicals do. They tend to stay in one area—at least that’s what we’ve been advised by our consultants.”

More Questions

Someone asked if the DEC had begun placing the interceptor wells to contain the plume.

Carey said that the DEC was doing some work to the north, “but there aren’t any [wells] at the leading edge of the plume yet. So it’s still moving toward us and this is what we’re fighting and arguing for: to get to that leading edge and stop it.”

“You really have no idea how to stop the plume,” an attendee called out.

“I completely disagree with the statement,” Carey firmly replied. “Because the technology we have been advocating for has been used successfully….it’s a proven technology, so [your statement] is not true.”

Cary was quizzed at how the Navy was responding to its cleanup responsibilities.

He related that the Navy holds twice-annual meetings at the Bethpage Community Center to give progress reports.

“Every time we attend it’s the same old story with them,” Carey said. “They think they’re doing a great job. They tell us how much [contamination] they’ve removed from the plume. And yet, we get the reports from all the monitoring wells and the concentrations keep getting greater and greater. We don’t believe in the approach [the Navy] signed on for.”

By that he meant treating only hot spots with TCE concentrations of greater than 1,000 ppb. For the past several years the Navy has been seeking to buy property at the edge of a contaminated area it has named RE-108. Located near the intersection of Hempstead Turnpike and Hicksville Road in Plainedge, such a property would need to fit an 80×100-foot building to house a treatment facility. In 2009, the Navy had set up a similar facility to treat a hot spot within the confines of the Bethpage Water District. Officials and residents have criticized the slow pace of the Navy’s efforts, as the plume continues to flow southeast.

Carey said he understood that such a property would be hard to find in that densely concentrated area.

“We identified several commercial/industrial properties for sale, but [the Navy by law] can’t disclose to us whether they’re pursuing them or not,” he noted.

Massapequa resident Denis Darnaud called out, “What do you do [regarding the Navy]?”

“We get up and question them. We call them out on it,” replied Carey.

“As this plume comes closer and closer, everybody’s just talking about it, and blaming the DEC and the U.S. Navy,” Arnaud stated. “But you know what? In 10 years, this thing [plume] is going to be here.”

“I agree, and that’s why Massapequa has taken such a strong position,” Carey said, going on to say that the MWD has spent more than $400,000 on legal fees to fight the Navy ROD, and this money is not reimbursable. As far as any lawsuit, the district cannot sue the responsible parties unless and until one of its wells is contaminated.

“All we can do is bark as loud as we can here in Massapequa,” observed Carey.

“So, we have to basically wait?” wondered Darnaud.

“Well, you can write letters,” Carey said, then, referencing the less than expected turnout, he stated, “I hoped to get two or three hundred people tonight. We reached out to thousands of people. The only way to get action is if the public speaks.”

“What’s the timeline for hydraulic containment?” an attendee asked.

Carey said the DEC hopes to start sometime next year, but noted that the process was already behind schedule.

“So there’s not much more we can do here,” he continued. “We can’t borrow $150 million, and it’s not our property to put the recovery wells in. It’s way beyond our scope.”

Carey said that full containment of the plume, according to estimates supplied by MWD consultants, could cost as much as $400 million over a 30-year period.

“The commitment of the governor for $150 million will not get the whole job done, but it’s a good start to get to the leading edge and get things underway,” Carey asserted.

“Is it necessary to install a home filtration system? How effective are they?” Carey was asked.

The superintendent said he would not recommend it, saying that the MWD meets all drinking water standards. In addition, home systems require a great deal of maintenance and his office often gets calls several months after a resident has installed such a system. They usually complain of a bad taste and odor. District technicians often find that the filter needs to be replaced.

Asked if the MWD can join the other districts in suing the responsible parties, Carey reiterated that the legal opinion he has gotten is that this can’t be done until one of the MWD wells is impacted by the plume.

“We’ve spent a lot of money on those legal opinions,” he pointed out. “Believe me, if we could have sued, we would have by now.”

Susan Hayes of Massapequa asked, “Why is the Navy not taking responsibility for a quicker cleanup?”

“Up until recently, they believed that the plume would dilute the further south it went. The monitoring wells have proved otherwise,” answered Carey. “The state did not take a tough enough position, and this is the result of it. Again, the concentration is growing, the [plume] size is growing, and for [the Navy], in my opinion, it’s all about money.”

Final Words

MWD Water Commissioner Thomas McCarthy told the assembled, “If they were going to build a shopping center two blocks from your house, you’d get your neighbors together and hold up signs protesting the shopping center—because you don’t want it in your back yard. Well, guess what? This [plume] is in your back yard. It’s coming. You’ve got to start making noise. The time to act is now. If we wait too long, it’s going to be too late. You’ve got to keep rattling the cages and get your neighbors out.”

Bill Pavone of Seaford is served by New York American Water, but has become an active participant at these occasional meetings dealing with the plume. He noted that the plume was 600 feet from his house, but the sense of urgency was missing because it was deep underground.

“If it was on the surface and being treated on the surface, it would be a whole other ball game,” he said.

After the meeting, Anton Media Group talked to Massapequa residents Susan Hayes and Denis Darnaud.

“Somebody has to be held accountable. This is our [drinking] water,” Hayes said.

Darnaud is retired from Cablevision, and related that he worked in a former Grumman building in Bethpage and was familiar with the contamination and the plume.

Yes, he replied with a chuckle, they drank bottled water at work.

“It’s very serious,” Hayes stated. “[It affects] your health, the environment and your personal investment. I just feel no one’s taking responsibility.”

Hayes said she wants to get more involved in the issue and drum up interest among her friends and neighbors.

“People have no idea how bad this is,” Darnaud reflected.

“I turned around, and this was such a dismal turnout,” summed up Hayes.

The Senator Talks

New York State Senator John Brooks (D-Seaford) attended the meeting and told Anton Media Group, “The governor has taken on a leadership role, and is putting pressure on the federal government. In the end, this is a federal problem.”

Brooks said it was ironic that President Trump had visited Bethpage back in May to hold a summit on dealing with MS-13, the violent gang. There is no MS-13 problem there, he pointed out, but there is a plume problem—which the president did not address.

“So I think we have to continue putting pressure on the federal government,” said Brooks, who added, “I’ve spoken to the [state] commissioners of environment and health and they’re confident that they’re going to have a workable [remediation] plan shortly. We have to see what it is and then go after the federal government and get the money.”

Brooks mentioned how President Trump found $12 billion in the budget to support farmers who will be hurt by his tariff policies.

“Well, the government created this [plume] problem too, and has got to put those funds out,” he said. “The federal government needs to step up. If that plume continues and gets into the Great South Bay, we’ve got real problems. It would be a national disaster.”

Summed up Brooks, “We historically have mismanaged this natural resource, the only source of water we have. We got a chance to clean this right now because its semi-isolated. But we have to have a working plan and then be aggressive with fully funding it. And bring the president back [to Bethpage] for a different reason. Because there is no MS-13 there, but there is a plume there.”