Merrick, N.Y. Fall 1963. As their classmates raced ahead on the school track, two seventh graders lagged behind.

Coach Phelps warned: “If you finish under seven minutes, boys, you’re running it again.”

“Gee, coach,” Bennett Cohen shouted back. “If we can’t do it under seven the first time, we sure aren’t doing it under seven the second time.”

Jerry Greenfield — the other slow-footed runner — was awestruck.

“I realized Ben was someone I wanted to get to know,” he recalls.

The feeling was mutual. That day at Merrick Avenue Middle School, two boys formed a friendship that’s still going strong half a century later. From that friendship between outsiders sprung Ben & Jerry’s, not only one of America’s favorite ice cream brands, but a pioneering force in the annals of socially conscious business management.

The friendship reflected the boys’ shared experiences dealing with the usual rites of 1960s adolescence: challenging authority, sticking up for friends in trouble, making new friends and trying out new roles. In junior high and again at Sanford H. Calhoun High School, Jerry was known for standing up to bullies; getting top grades; and was, close friends say, a hoot to hang out with. Bennett — later Ben — was known for his cello playing, his enthusiastic performances with a jug band, and his success as yearbook editor.

For a couple of summers Ben drove a Pied Piper Ice Cream truck, sometimes helped by Jerry, friends recall. The experience selling ice cream would come to define their lives.

They split up after graduating in June 1969. Jerry pursued pre-med studies, Ben stumbled through several colleges before dropping out. Four years later they reunited in Manhattan, dividing the rent on Ben’s cramped East Village apartment. Ben had tried throwing pottery, teaching at an alternative school, working as a short-order cook, and driving a cab. Jerry had been rejected twice from medical school and was at loose ends.

Jerry recalls with a smile: “Basically, we’d failed at everything we tried.”

With few appealing options, the roomies decided to try their hand in the food industry. The choice: bagels or ice cream? Jerry discovered Penn State’s $5 mail-order course in ice cream making; they split the fee. Thus was born Ben & Jerry’s homemade ice cream.

Seeking a rural college town that had no ice cream parlor — and therefore no competition — the buddies settled in Burlington, Vt., home of the University of Vermont. Acquiring a vacant gas station, they converted it into the first Ben & Jerry’s.

Summers were great. In winter temperatures dropped to minus 20. Customers stayed home. To keep cash flowing, Ben sold local grocery-store owners on carrying the brand. He soon spread distribution across the state.

The partners played the roles of quirky, good-natured rebels always ready to challenge establishment rules. Their local-sourcing policy bolstered Vermont’s dairy industry. They positioned themselves as environmental protectors, opposing such practices as genetic modifications (some food activists targeted them anyway.) Backing up their beliefs with their checkbook, they bolstered the careers of many artists, artisans, and other creative types.

Their antics made the news. When Häagen-Dazs’ corporate parent at the time, Pillsbury, blocked Ben & Jerry’s first distribution deal, Jerry fashioned a cheeky David-vs.-Goliath PR campaign — “What’s the Doughboy Afraid Of?” — that got national press. A Time magazine cover story in 1981 proclaimed Ben & Jerry’s the best ice cream in the world. Ben tested recipe after recipe before concocting a new cherry-flavored batch he named — what else? — Cherry Garcia.

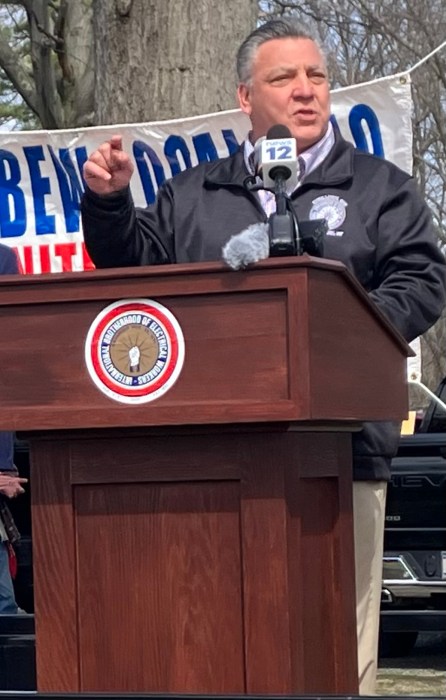

The company Ben and Jerry formed to sell ice cream in Vermont turned 40 this spring, an anniversary the founders celebrated with a series of look-back presentations around the country. They touched down in Garden City September 12 with a rare Long Island appearance, each spending the day with relatives (Ben) and old grade school classmates (Jerry) before speaking at Adelphi University that night.

Speaking first, Jerry related a few stories about how he and Ben struggled in the early years. Raising money was a constant challenge. Jerry talked about how their business grew, not in spite of their support for local humanitarian causes, but – he asserted – because of it.

“Social justice and giving back to the community are baked into Ben & Jerry’s,” he said.

Speaking next, Ben brought Jerry’s narrative up to date. Noting the sale to Unilever, he asserted the giant corporation had succeeded in preserving their company’s social mission — especially over the past five to seven years. He quoted Schopenhauer and the Harvard Business Review.

Launching into the kind of stem-winder associated with political campaigns, Ben’s voice rose as he demanded campaign finance reforms, endorsed marriage equality, and spoke out for Black Lives Matter. He congratulated Nike for supporting Colin Kaepernick and closed with a sly but crystal-clear rebuke of President Trump.

“Let’s make America kind again,” he orated.

After years of advocating for sixties ideals, Ben and Jerry are no longer voices crying in the wilderness.

“People used to laugh at us when we spoke to business groups at programs like this one,” Ben said to an audience clearly on his side.

Added Jerry: “Now we’ve been mainstreamed.”

The audience laughed. On that note the program ended. Everyone stepped into the lobby for an old-fashioned ice cream social. No need to ask which brand of ice cream was served.

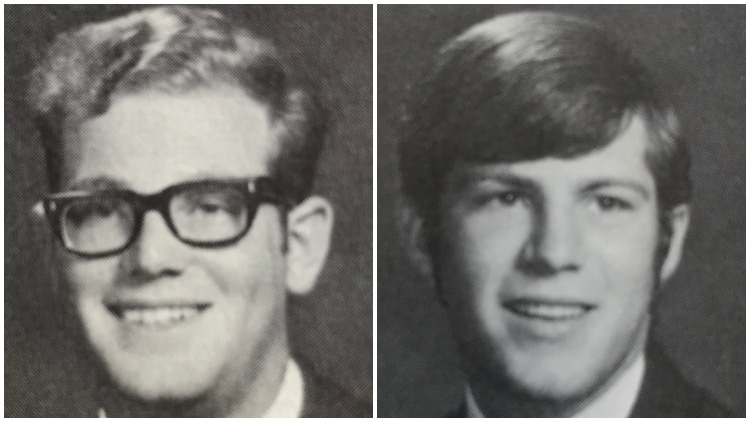

Ben and Jerry in High School

Ben & Jerry’s Calhoun High School classmates reflect on the famous duo.

“Jerry and I were in Honor Society together; Bennett was yearbook editor. We were in different cliques: I was kickline captain whereas they did the outsider thing, the rebellious, protest-the-Vietnam-war thing. Both were exceptionally bright. What they had to say was thought-through and intelligent. Bennett was more into people’s faces than Jerry. Back then it was hard to tell if they were destined for greatness or destined for jail. Bennett especially could have gone either way.” -Tricia Mcgrath-Margas, Scotia, N.Y.

“I opened the first Ben & Jerry’s Homemade franchise in New York State; that was in 1983. One day Ben’s visiting me at the store and I get a phone call. It’s from Jerry Garcia’s lawyer with a message for Mr. Cohen about Cherry Garcia. Ben takes the call, starts telling the guy how much he loves Jerry and the Grateful Dead. First it’s: ‘What were you guys thinking?’ Then: ‘You can use the name provided you contribute to Jerry’s charity.’ Ben says ‘yes,’ right away.” -Jeff Durstewitz, Saratoga Springs, N.Y.

“These are two guys who never sold out, were always true to their core beliefs. They want to help people, they want justice for all and they want the environment to be good. They want to give back to the farmers in Vermont. They could have started their business on Long Island, but there are a lot more dairy farmers in Vermont.” -Zach Albahae, Coral Springs, Fla.

“Jerry was the kind of person who’d stick up for his friends. He got into a fight on the basketball court once standing up for a smaller kid. He was well liked at school. I’m sure Ben was too, I just didn’t know him as well.” -Dr. Andrew Newman, Merrick

“Jerry and I shared an affinity for Motown. We went to the Apollo to see James Brown. We were big into Otis Redding and Aretha Franklin, too. It was our introduction to African-American culture; Merrick was all white. They both became big Grateful Dead fans. We were all heavily invested in the counterculture music: Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, The Beatles. I remember Ben trying to explain the Grateful Dead to his parents. His mother said, ‘So, are they happy they’re dead?’ That line became famous.” -Ronnie Bauch, Manhattan