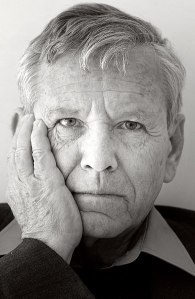

Israeli writer Amos Oz died of cancer on Friday, Dec. 28, at the age of 79. Considered a contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Oz wrote novels, essays and short stories that have been published in 47 languages. His autobiography, A Tale of Love and Darkness, chronicles his youth growing up in Jerusalem at the origins of Israeli statehood. The book, along with the rest of Oz’s body of work, ultimately addresses big questions about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Oz had every reason to be a staunch Zionist, which, at least in the beginning of his life, he was. In A Tale of Love and Darkness, Oz tells a heartbreaking story that takes place in the “early hours of Nov. 30, 1947,” just after the UN Partition Plan for Palestine had passed. At three or four in the morning, 8-year-old Oz was lying in bed when his father climbed into bed with him and, with tears in his manly eyes, whispered about “what some gentile boys did to him at his Polish school in Vilna, and the girls joined in, too, and the next day, when his father, Grandpa Alexander, came to the school to register a complaint, the bullies refused to return the torn trousers but attacked his father, Grandpa, in front of his eyes, forced him down onto the paving stones in the middle of the playground and removed his trousers, too, and the girls laughed and made dirty jokes, saying that the Jews were all so-and-sos, while the teachers watched and said nothing, or maybe they were laughing, too.”

Oz’s father ultimately said to him, “From now on, from the moment we have our own state, you will never be bullied just because you are a Jew and because Jews are so-and-sos. Not that. Never again. From tonight, that’s finished here. Forever.”

This statement captures the strong emotion surrounding Israeli statehood. The long history of Jews being unwelcome anywhere in the world and having to hide their religion is not only restricted to Ashkenazi Jews like Oz’s father who were victims of pogroms and the Holocaust; the Persian Jews of Great Neck can also relate.

After the Allahdad of the 19th century, my Mashadi-Jewish ancestors had to pretend to be Muslim in order to avoid being discriminated against or even killed, yet they bravely practiced their religion in basements and became engaged to be married at young ages so to hold on to their tradition and community.

Indeed, Oz had every reason to be a staunch Zionist. Yet, as he grew up, met Palestinians, consumed volumes of history and joined a kibbutz where people thought a little differently, Oz became more familiar with the nuances surrounding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In his essay collection, How to Cure a Fanatic, he debunked myths and proposed a vision for peace between the Israeli and Palestinian people.

In How to Cure a Fanatic, Oz wrote “Both side have internalized the self-image

of a victim, which often begets a certain degree of self-righteousness, neurosis and insecurity.”

Here, Oz was not denying how both Jews and Palestinians have been victimized. Heaven knows they have been victimized. In fact, Oz identified both sides as victims—of Europe. The myth was when they misconstrued each other as the enemy rather than uniting in their common, real victimhood by Europe.

In A Tale of Love and Darkness, Oz wrote, “When we look at [the Arabs], we do not see fellow victims…we see not brothers in adversity but pogrom-making Cossacks, bloodthirsty anti-Semites, Nazis in disguise, as though our European persecutors have reappeared here in the Land of Israel, put keffiyehs on their heads and grown mustaches, but they are still our old murderers, interested only in slitting Jews’ throats for fun.”

In Oz’s opinion, this kind of mythology, which exists on both sides of the conflict, gets in the way of a two-state solution.

Oz understood the stakes of the situation on the Jewish side as well as anybody.

Yet he grew up to realize that the conflict is much more complicated than one between good and bad or right and wrong, that it’s actually, he wrote, a conflict between good and good, right and right.

Unfortunately, Oz did not live to see his dream for peace come true, but to his dying day the great Israeli writer remained hopeful that a two-state solution is still possible.