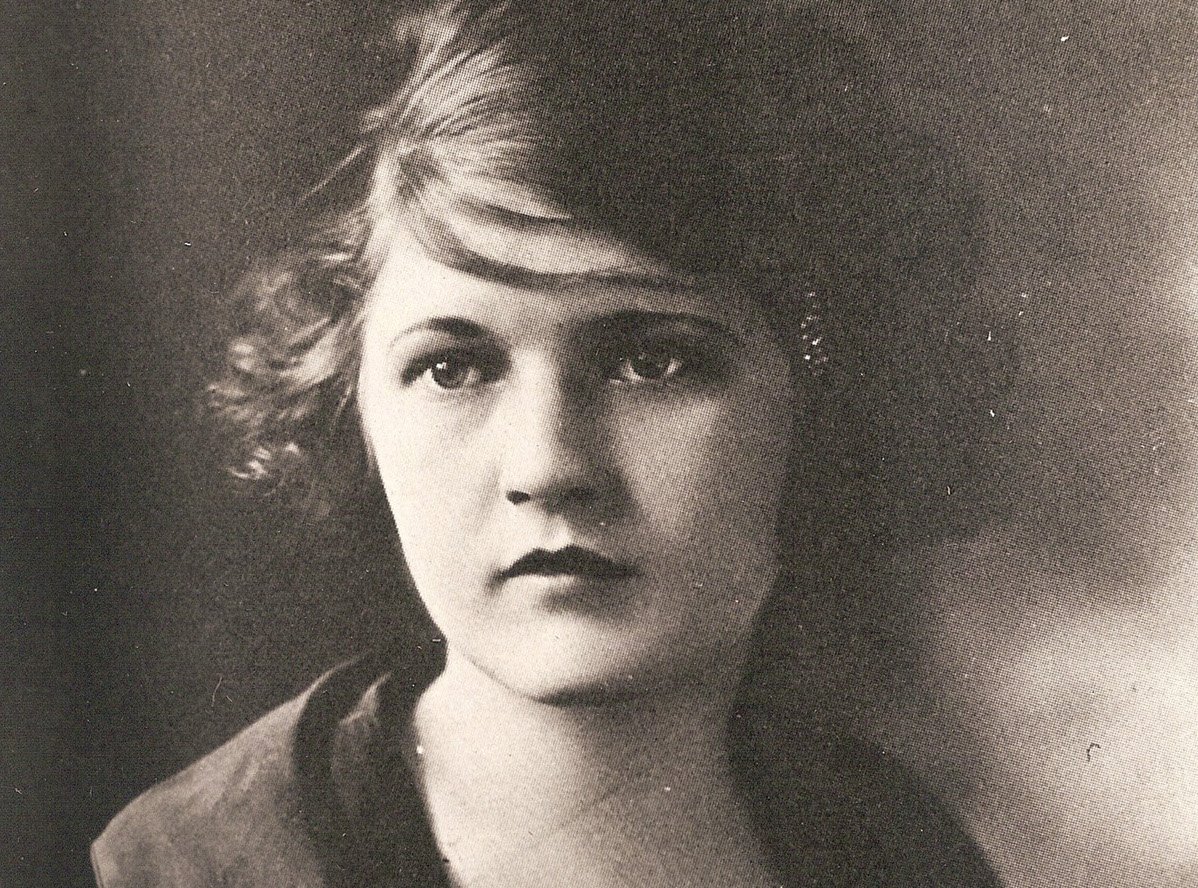

She was a high-spirited, unconventional 1920s Southern belle and aspiring ballerina embracing independence. He was a struggling novelist bedazzled by her wit and unconventional behavior who dubbed her “America’s First Flapper” and stole her words. They loved each other deeply but destructively, across Alabama, Connecticut, France, Switzerland, Maryland, and Long Island.

Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald and F. Scott Fitzgerald practiced emotional cruelty, drunkenness, infidelity, plagiarism, and mental illness. And yet they remain celebrities personifying the rebellious youth of the Lost Generation.

WHEN ZELDA MET SCOTT

Merriam-Webster defines “flapper” as “a young woman of the period of World War I and the following decade who showed freedom from conventions.” As the spoiled daughter of an Alabama Supreme Court Justice, Zelda flirted, drank, and smoked in public. She turned 18 and graduated high school in 1918, as the war ended. She met 22-year-old Scott at a Montgomery country club dance; he was a U.S. Army officer stationed nearby, after flunking out of Princeton University.

Acclaim for his 1920 debut novel, This Side of Paradise, brought sudden prosperity as the Roaring Twenties burst upon the country. As he chronicled the Jazz Age, she danced on tables and cartwheeled across hotel lobbies; after their 1920 marriage, she splashed in Washington Square fountain. They indulged their whims, spending wildly beyond their means.

The next few years bore fruit: They honeymooned in Westport, Conn., and Frances (“Scottie”) Fitzgerald, was born in 1921. In 1922, they moved to 6 Gateway Drive in Great Neck, where Scott wrote magazine short stories and an unsuccessful play. Zelda dreamed of becoming a prima ballerina, painted fantastical scenes and family portraits, and wrote the essay Eulogy on the Flapper for Metropolitan Magazine. She would pen more than a dozen articles and stories; many appeared under the joint byline “F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald.”

Some say the seeds for Scott’s masterpiece The Great Gatsby were sown in Westport, while others insist they germinated in Great Neck on “that slender riotous island.” In any case, the Fitzgeralds befriended their LI neighbor, railroad industry heiress Mary Harriman Rumsey, whose Sands Point estate at 235 Middle Neck Road reportedly inspired Scott’s “East Egg” setting for Jay Gatsby’s mansion.

Gatsby was published in 1925, a year after the Fitzgeralds moved to Paris. Zelda was Scott’s muse, and more: He quoted her words as the voice of his female characters and took material from her diary and letters for his writings. As she wrote in a book review, “Mr. Fitzgerald … seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home.”

THE MAD WIFE

By the late 1920s, their lives were disintegrating. He could not write without drinking to excess; she practiced ballet excessively yet refused an offer to join a Naples dance company.

She accused Scott of having a homosexual relationship with his friend Ernest Hemingway (Hemingway called her “crazy”), had an affair with an aviator, and asked for a divorce. Scott locked her in their Riviera house and she attempted suicide. Friends noticed serious behavioral shifts and, suffering from nervous exhaustion and hysteria, she entered a health clinic in 1930. The diagnosis was schizophrenia; today, the condition might be called manic depressive disorder, characterized by her spending sprees, melancholy, and passionate personality.

During her confinement she wrote her only novel, Save Me the Waltz, in six weeks. The largely autobiographical 1932 work was panned by Scott and the public, crushing her confidence. She continued painting but abandoned writing after he said, “…You are a third-rate writer and a third-rate ballet dancer.”

Some say that Scott confined Zelda because she disturbed his writing; he blamed his inability to finish another novel on medical debts. Scott moved to Hollywood in 1937 to write scripts, dying of a heart attack in 1940 at age 44.

She was discharged and readmitted for breakdowns and relapses for the rest of her life. In 1948, a fire tore through a North Carolina mental hospital where Zelda was locked in a room awaiting shock treatment, killing her and eight other women.

Critics have reassessed her work. The New York Times’ Michiko Kakutani wrote that Zelda “managed to distinguish herself as a writer with, as Edmund Wilson once said of her husband, a ‘gift for turning language into something iridescent and surprising.’”

Art gallery curator Everl Adair concluded that Zelda’s artwork “represents the work of a talented, visionary woman who rose above tremendous odds to create a fascinating body of work … that inspires us to celebrate the life that might have been.”