All through her life, she broke the rules. Her formal education ended at age 13. She challenged society’s notions about womanhood at a time when few women worked, and set the gossips’ tongues wagging with her scandalous two marriages and two divorces, adultery with a man 10 years her junior, and affairs.

But her force as a writer crushed the notoriety: She won a legal suit revolutionizing copyright law to reimburse writers for profits from plays based on their works. A women’s rights advocate, she signed a writers’ petition on women’s suffrage before the House of Representatives in 1910, a year after building her Plandome estate on the North Shore.

Frances Hodgson Burnett penned adult novels, children’s books, and short stories — 52 novels and 13 plays — and produced works for the stage. At one point she wrote six books in 10 years, despite battling ill health. What drove her?

Riches to Rags

Like her riches-to-rags-to-riches characters, the author started life in 1849 in affluent, mid-Victorian Manchester, England. But their fortunes collapsed with her father’s death when she was 4 years old. Her widowed mother ran their iron foundry until America’s trade declines caused it to fail and forced the family to move to a marginal area. The behavior of other 10-year-old street children around Frances Hodgson fascinated her; observing their Dickensian existence nurtured her flair for fiction, writing on a slate or on old account books.

Still impoverished, her family moved to America to live with relatives in a log cabin near Knoxville, Tennessee. But the Civil War economy worsened and their mother’s health failed; only neighborly generosity kept them alive. The practical, independent little girl stepped up, opening a small school, raising chickens, and teaching piano.

In 1867, using postage she paid for by selling grapes, she submitted a story, for “remuneration,” as she put it. Godey’s Ladies Book published the 17-year-old’s first two stories, paying her $35. Her serialized magazine pieces became popular and earned enough to support her family after their mother died in 1870.

Her first adult novel, That Lass o’ Lowrie’s, contained realistic detail about a feisty woman working in a coal mine. It was published in 1877, four years after she married — reluctantly — Dr. Swan Burnett.

A self-described “story maniac,” Frances Hodgson Burnett churned out fluid adult manuscripts needing little editing. She typified the ”new woman,” wrote biographer Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina: self-supporting, independent, and a shrewd businesswoman. The New York Times praised her “treatment of adultery, spousal abuse, illegitimacy and female independence.” Burnett also zeroed in on unhappy unions, based on her faltering marriage.

Garden Therapy

In 1886, her Little Lord Fauntleroy, about a curly-locked boy in velvet and lace modeled after her son Vivian, sold half a million copies. Attributing her dedication to a spiritual force, she wrote constantly, her sons at her feet under her writing desk. She bought extravagantly — clothes, houses, and gifts for relatives; more than 90 gowns; and home decor for her English estate, Great Maytham Hall. And, exhausted and anemic, she suffered nervous breakdowns.

She crossed the Atlantic 33 times for business and pleasure, often with men, unchaperoned. Her stressful marriages, bitter divorces, and the death of her teenage son Lionel in 1890 brought on depression. She found comfort in what Gerzina calls ”a romantic friendship” with Harper’s Bazaar Editor Elizabeth Garver.

In 1897, her plays earning $1,000 a week, Burnett settled at Maytham. There, outside under the trees, rejuvenated, she wrote A Little Princess in 1905.

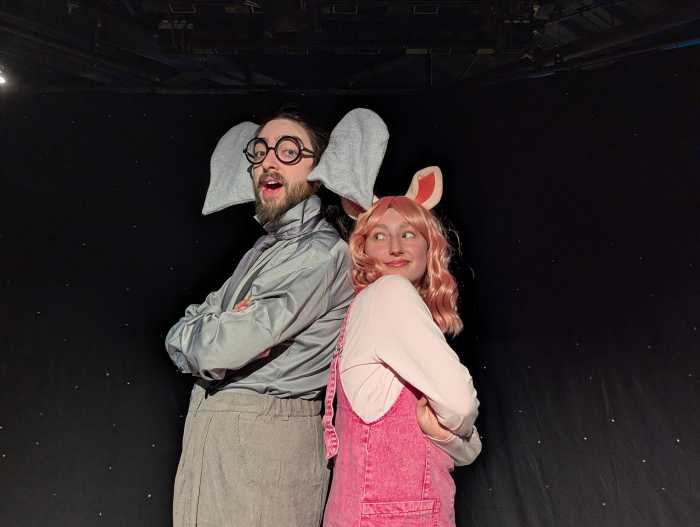

Some say Maytham’s crumbling garden wall — and its tame robin — inspired Burnett; others believe it was her childhood home’s back garden. The Secret Garden (1910) was written among hundreds of rose plantings at Fairseat, her Plandome estate. It told of an orphaned girl finding solace in a neglected garden, who “made herself stronger by fighting with the wind.” Like her other children’s classics, it rose above the era’s florid style and morality.

She spent her last years at Plandome among spacious gardens and roses that sloped down to Long Island Sound. In 1914, she wrote, “To live in the best suite of rooms in the best hotels in any part of Europe is strict economy in comparison to living at Plandome Park, Long Island.’’

She died in 1924 and was buried in the Roslyn cemetery. A fire later destroyed Fairseat except for its original stucco carriage house and garden balustrades.