Born December 31, 1933, Harvey Weisenberg was a police officer, special education teacher, elementary school assistant principal, restaurant owner, coach, lifeguard, and an accomplished politician.

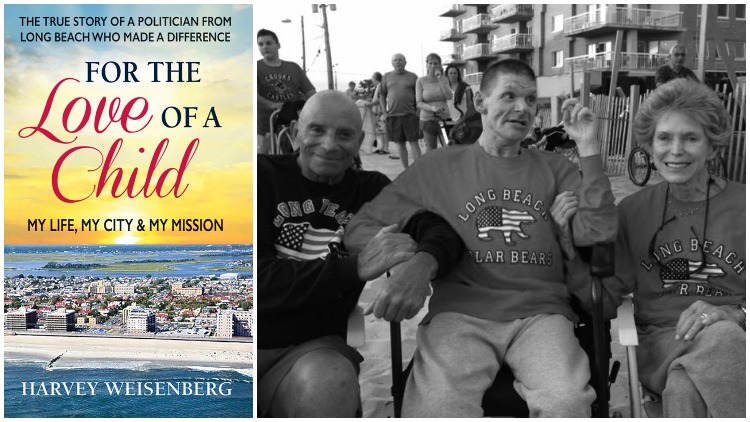

He served for 13 years on the Long Beach City Council and 25 years as a New York State assemblyman, during which time he was responsible for more than 337 bills signed into law. For more than 50 years, he was a devoted husband to his recently deceased wife, Ellen, and a loving father to their now 60-year-old son, Ricky, who is challenged with cerebral palsy. Weisenberg’s recently published autobiography, For the Love of a Child, My City & My Mission by Square One Publishers, is a love story that encompasses extraordinary accounts and heartfelt sentiment about Weisenberg’s own remarkable personal and professional life.

“I am one of the happiest people I know,” he writes in the book. “I didn’t always win. I got into fights within my own party’s leadership—still do—and I’ve been double-crossed more than once … But I never stopped trying, and I’m glad I didn’t.”

Weisenberg is a down-to-earth, warm-hearted, brilliant man. He says, though that his greatest achievement is meeting the love of his life, Ellen, and her son, Ricky.

They met one magical summer when he was a lifeguard. She was accompanied by her children — son Ricky and two daughters, Julie and Vickie. Though her outer beauty did not go unnoticed, Weisenberg says he was immediately drawn to Ellen’s kind, caring and patient nature, especially with Ricky.

“The love that she was giving this child,” he recalls. “It just touched me. I honestly believe that God gave me an angel, a saint and a mission. Ricky is the angel, my wife was the saint, and my mission is doing everything I can to help people — and that’s the God’s honest truth.”

The family enjoyed “simple things in life — the beach, concerts outside, summer on the boardwalk,” he says.

Weisenberg was fascinated by Ricky’s effect on others.

“I got to know him,” he says. “He has intelligence. He can’t speak or cry, but his presence was surely felt by all. Some would bless him, others would turn away.”

Weisenberg saw firsthand not only how things could go wrong — Ricky was abused while institutionalized — but also how they could go right, as many caregivers showed Ricky love and support and care in spite of not being appropriately compensated for their work.

“They do the tasks no one else wants to do,” Weisenberg says. He became the “voice of people who did not have a voice.”

The Weisenbergs also established the Weisenberg Foundation, a nonprofit organization that supports and advocates for people with special needs, their families and caregivers.

Never intimidated by politics, Weisenberg used his professional position and passion to rally for the cause.

Adam’s Law requires safety restraints in taxicabs and delivery vehicles to be clearly visible, properly maintained and easily accessible for passengers.

Louis’ Law requires that life-saving defibrillators be available in schools.

Jonathan’s Law requires residential care facilities to notify and inform parents and legal guardians of children and adults receiving services of incidents involving their loved ones.

Leandra’s Law declares that adults who drive drunk with minors will be charged with a felony. Violators face up to four years in prison and DWI offenders who kill minors who are passengers could face up to 25 years in prison.

In 2013, Weisenberg fought Gov. Andrew Cuomo to restore $90 million of previously eliminated funds to the state budget to support the disabled population.

In 2018, he secured $45 million in funding in the state budget for direct support professionals who care for developmentally disabled individuals. The average salary for these workers increased from $9 per hour to $14 an hour.

Weisenberg says it is critical to forever create awareness.

“The real heroes are the families that came forward to bring these issues to the forefront,” he asserts.